In this episode we look at different ways to track fitness. Previously we have talked about VO2 max and Heart Rate Variability (HRV), along with the trackers (ex. Fitbits) which are used to quantify such physical activity markers.

This episode highlights difficulties and advances in translating physical activity data into meaningful information. We seek to understand what tracking fitness actually tells you about how fit you are? How is your fitness evolving due to training and other changes you are possibly making to your lifestyle? Ultimately, can we usefully quantify cardiovascular fitness yet?

Aiming to accurately capture this, our guest has developed his own approach to analyzing fitness and this is the main topic of this episode.

– Marco Altini

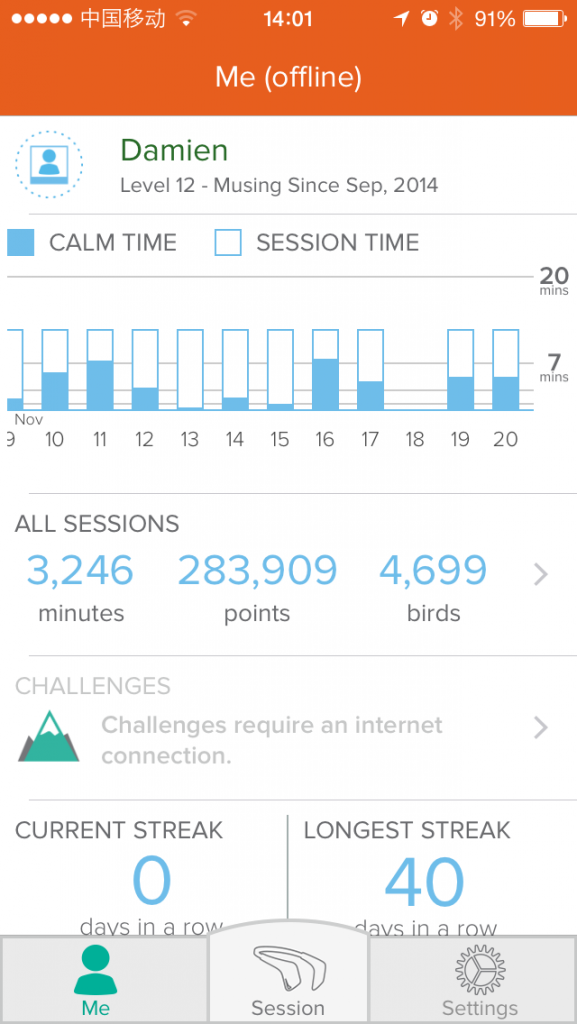

Our guest is Marco Altini, a PhD Data scientist and entrepreneur working in the middle of the quantified self area. He has spent a lot of time working on heart rate, HRV, fitness, and physical activity analysis via wearable sensors.

Marco has published over 25 papers on the topic. He has a popular HRV4Training app, which is available on the iTunes store. I have used this app myself for over-training monitoring. So he has really done a lot of work in just this specific space.

If you’re in the quantified self community you probably know Marco already because a lot of his posts are widely circulated as these are normally rigorous and interesting. Today he heads up Data Science Activities at Bloom Technologies, where he is using technology and data to help women have healthier pregnancies. We also touch on that.

The episode highlights, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

What You’ll Learn

- Marco’s research interests and the science behind personalized fitness (3:49).

- Interpreting accelerometer, heart rate, or calorie meter device data (8:31).

- Modeling physical activities and normalizing body data to accurately determine energy expenditure (9:54).

- Using the VO2 max test as a marker for quantifying cardiorespiratory fitness (15:49).

- The VO2 max test in tracking for performance or health benefits of exercise (19:24).

- Interpreting VO2 max test results and the drawbacks of normalizing (25:13).

- Using technology for normalizing results and improving accuracy of quantified fitness (25:54).

- How to track individual fitness changes (30:23).

- How Marco’s StayFit app works and distinguishing features from other similar apps (30:38).

- Key points of analyzing energy expenditure as a fitness marker (33:44).

- Because fitness improves over long periods, accurate tracking should aim at long – term benchmarks (37:14).

- The complexity of the relationship between HRV and quantifying fitness levels (38:45).

- How Marco tweaked his app to adapt measuring heart rate in overall fitness equations (42:28).

- Normalizing fitness metrics and allowing for un-biased comparison between people (43:26).

- The importance of context when considering what normalized fitness metrics actually mean for an individual’s results (44:12).

- Comparing the advantages and limitations of tracking HRV vs. heart rate as fitness biomarkers (46:37).

- Tracking HRV and fitness parameters in order to prevent pregnancy complications – a Bloom Technologies project (48:22) .

- Discussing near-future market products and collaborations with major clinical research centers (51:54).

- How to obtain more information on the topics of this episode (52:50).

- How best to connect with our guest (53:36).

- Marco’s recommendations for learning about cardio fitness (53:52).

- Marco’s approach to tracking his body data on routine basis (54:34).

- Caveats and useful insight into tracking HRV as a cardiovascular fitness parameter (55:45).

- Marco’s number one recommendation for improving health, performance, and longevity (57:41).

Thank Marco Altini on Twitter for this interview.

Click Here to let him know you enjoyed the show!

Marco Altini (PhD), Bloom Technologies

- Marco Altini: Main website and biography, including a complete list of Marco’s research papers and publications.

- Bloom Technologies: A digital health company focused on helping expecting mothers have a healthy pregnancy. Marco leads data science activities – an integrated approach to studying physiological changes behavior and pregnancy outcomes.

- PubMed search for Marco Altini

- Marco Altini’s Twitter

Fitness Apps developed by Marco

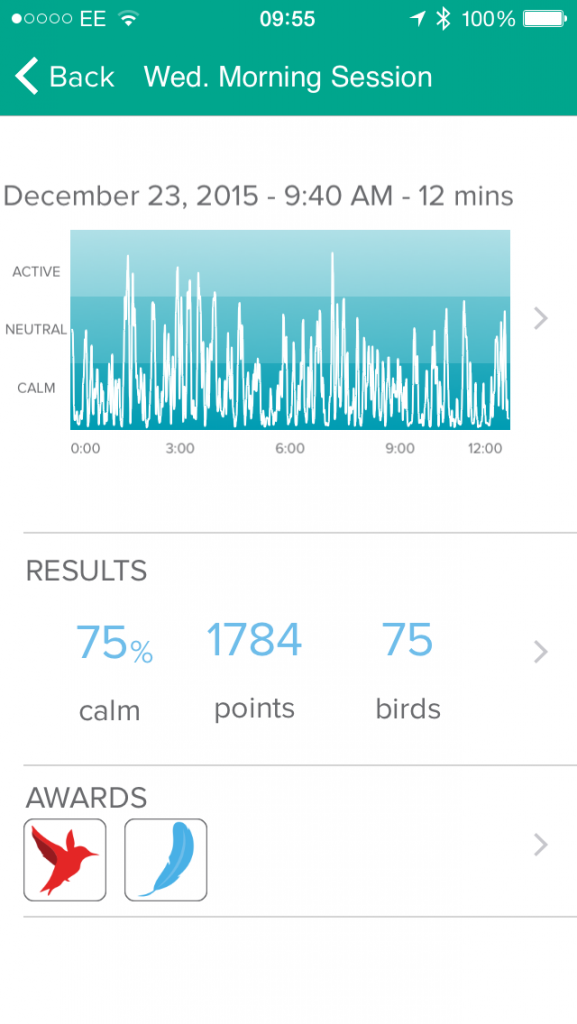

- HRV4Training: This app is useful for preventing over-training by measuring HRV and providing personalized feedback on your physical condition. Learn more on their website.

- StayFit: This app from Marco is based on a novel method for quantifying cardio fitness, known as the Fitness Index developed by Marco Altini. Some of the research backing this up was just recently (after this interview took place) published in the Artificial Intelligence Journal here.

Note: StayFit is not available on the Apple Store any longer. Marco has integrated the Fitness Index into his main app HRV4Training.

Tools & Tactics

Supplementation

- Lypo-Spheric Vitamin C: Liposome Encapsulated Vitamin C for Maximum Bioavailability; 0.2 fl oz. – 30 Packets | 1,000 mg Vitamin C Per Packet. Damien suggests taking this supplement in response to particularly low HRV test scores. As such, it can be used to prevent potential colds in a timely manner.

Tracking

Biomarkers

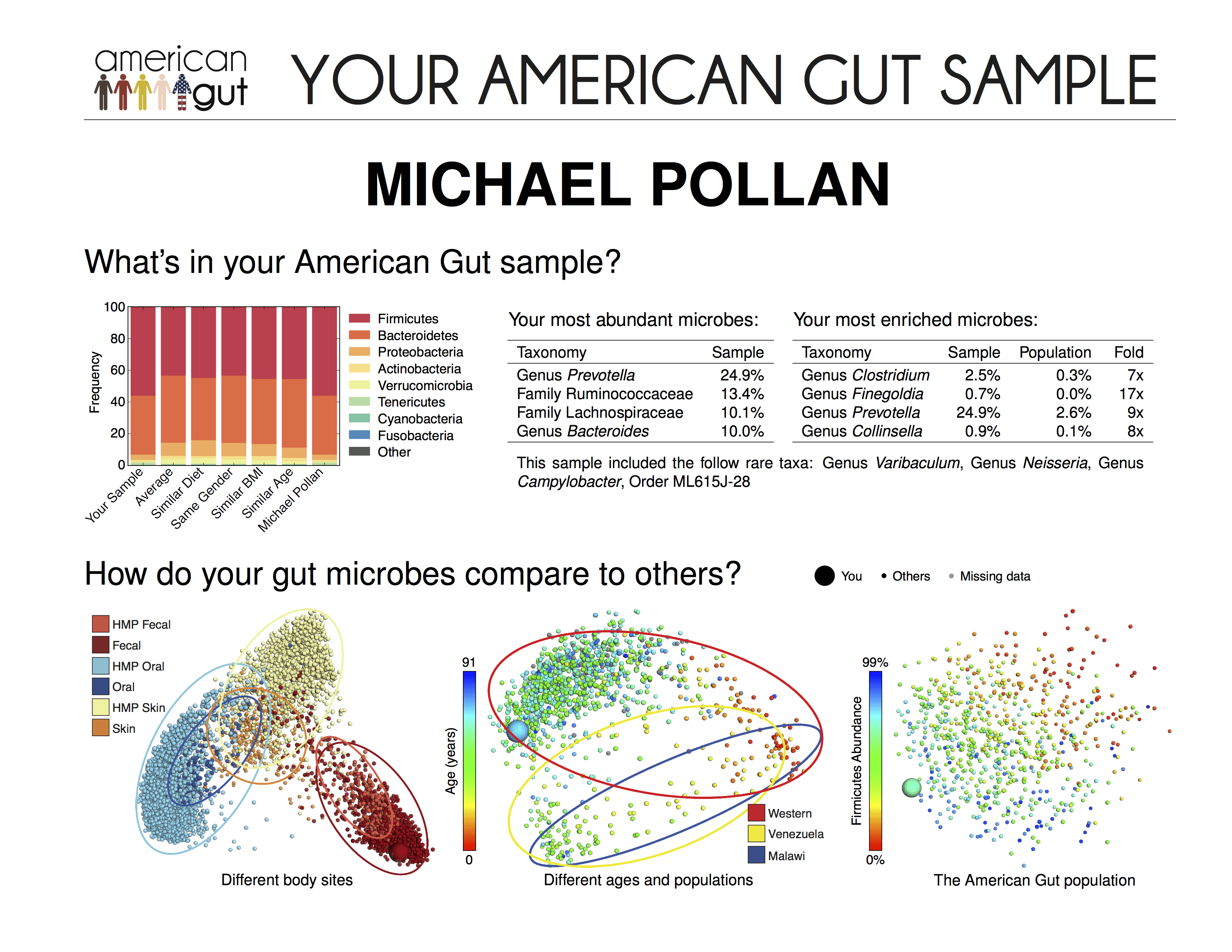

- Maximal Oxygen Consumption (VO2 max): This marker reflects the ability of your circulatory-respiratory system to provide oxygen to your muscles for sustaining exercise. Research has confirmed that low cardiovascular fitness is associated with higher disease risk, including heart disease. A running VO2 max test is more indicative of cardiovascular fitness compared to a biking test which does not require you to carry your entire weight forward. We have previously discussed this marker in the context of wearable devices which estimate VO2 max with Troy Angrignon in Episode 24.

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV): HRV is the measure of the change in the heart’s rhythm, measured as variations in para/sympathetic stimulation to the heart muscles. HRV is not an ideal marker for tracking fitness improvements because of day to day variability in results. Previously we covered HRV in the context of optimizing training in Episode 1 with Andrew Flatt, longevity in Episode 20 with Dr. Joon Yun. and using HRV to reduce stress in Episode 35 with Richard Gevirtz.

- Heart Rate: The speed of the heartbeat – measured in beats per minute (bpm). Lower heart rate is associated with stronger cardiovascular ability. Marco recommends tracking resting or active heart rate for tracking overall cardiovascular fitness. Heart rate increases by 10-20 bpm during pregnancy – an important factor to consider when quantifying fitness or risk for pregnancy complications.

Lab Tests, Devices and Apps

- Basis Peak: A watch functioning as a fitness and sleep tracker.

- Moves: An exercise tracking app which can detect the type of exercise being performed.

- FitBit: This company offers wearable devices which include cardiovascular fitness tracking. The FitBit Surge is a fitness watch that offers GPS tracking, heart rate monitor, all-day tracking, and sleep tracking. The FitBit Charge monitors physical activity and sleep quality.

- Runkeeper: An app which tracks running, walking, cycling, workout, pace and weight and which also lets you manually enter the activity you are performing.

- MyHeart Counts: A personalized tool that can help you measure daily activity, fitness, and cardiovascular risk developed at Stanford University.

- Steps: A pedometer and activity tracker app with measures how far you walk and how many steps you take.

Other People, Books & Resources

Organizations

- Stanford University, School of Medicine: Marco suggests the MyHeart Counts app developed by the Stanford School of Medicine as a starting point to understanding cardiovascular health and quantifying fitness.

- University of California in San Francisco (UCSF): Marco collaborates with UCSF in gathering reliable data for developing the Bloom Technologies’ pregnancy initiative.

Full Interview Transcript

[Marco Altini]: Thank you, my pleasure.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So I wanted to get first into a story about where you are at, and how you got into measuring fitness and looking at that specifically. What’s your background, and what’s your interest in this area?

[Marco Altini]: So basically I’ve been doing a PhD all around using wearable sensors to monitor energy expenditure. Well, let’s more say on their machine [04:12 check ‘machine landing’] aspects, so integrating multiple data streams [04:16 unclear] to accurate measurements of physical activity. Which is normally what we focus on is energy expenditure. So basically the intensity of the activity.

And taking a step back, let’s say most of the research in the field focused on the component of energy expenditure, which is due to physical activity, right? So body movement, because energy expenditure is actually composed of three elements. So we have diet induced thermogenesis, which is the energy expenditure we expend due to digestion, for example. And that’s something we consider as a sort of standard component, about 10 percent.

Then we have our basal metabolic rate, which is basically the calories we burn at rest. So if we take a bit of a simplistic view, this is what we would consume if we were not doing any activity. We lie in bed all day, and we still consume actually most of our energy which is due to this component. And then the third component is physical activity energy expenditure, which is the calories we burn when we move or exercise.

So by working a lot around this component and trying to estimate this more accurately using accelerometer and heart rate data, then I started focusing on aspects like personalization. Because when you use physiological data like heart rate to estimate energy expenditure you basically rely on parameters which are very well correlated with energy expenditure at the individual level. So for a single person, because of course heart rate is directly connected to oxygen uptake, which is also what we measure when we want to get the reference for energy expenditure.

At the same time there are individual differences between people so you need to try to understand how to model this difference between people in a way that your energy expenditure estimate coming from heart rate is accurate. And while working around this, basically you’ll get the work on what is the problem of basically normalizing heart rate between individuals, which is directly connected to fitness.

Because everyone tends to know that lower heart rate means better fitness. This is true at rest but even during exercise, which is, as a matter of fact, the principle behind, for example, sub-maximal fitness tests.

So, people are brought to the gym and they do an exercise to a certain intensity, and then based on what their heart rate you get, basically a surrogate of their fitness level. And all of that came back as something that you need to account for also when you measure energy expenditure because the whole reason behind normalization is that our metabolic response to exercise is not affected by fitness.

So just as an example to clear this up, if we think about, let’s say two individuals which are the same in terms of age, body weight, body mass, pretty much the same anthropometric characteristics. Then when they do a certain activity, they consume the same energy. So it’s the same kilocalories per minute because that’s mainly driven by the type of activity and the body mass.

However, these two individuals could be having a very different fitness level. So let’s say that one is very fit and while doing this activity their heart rate is very low, and the other one is very unfit and the heart rate is much higher. Then if you use heart rate to estimate the energy expenditure, you would be over or under estimating for one of these people.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So the one with the fast heart rate is over estimating?

[Marco Altini]: Yes. If you have a higher heart rate and then you don’t take into account that there is a difference in fitness, then you will assume this person is consuming more energy because the heart rate is higher with respect to the average, let’s say.

But that’s not the case because actually metabolism is not affected by fitness and there have been quite a few studies looking both at rest and during exercise, and given basal metabolic rate the component of energy expenditure.

[08:31] [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So what we’re saying is there are a lot of devices out there right now which are attempting to assess how many calories you’re burning in addition to the steps. So when you’re looking at that, actually, it’s a bit more complicated than the standards currently use, right?

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, exactly. Especially manufactures which are using, providing sensors with heart rate. They like to claim that just because there is heart rate they will be more accurate. And let’s say that using heart rate certainly is already a step forward compared to accelerometers because you can, with minimal effort already take into account energy expenditure for many activities which don’t involve body movement. Right?

For example with accelerometers we have limitations even just biking, because you might have the accelerometer in a place where it doesn’t move when you do these activities. So by using heart rate you can solve, partially, these issues. Because of course your heart rate will increase.

It doesn’t matter if you don’t move if you are doing exercise which is intense and of course requires your heart to pump more oxygen to your muscles. At the same time, due to the fact that the relation with heart rate is very personal, then you need to be able to make an extra step and model that if you want your system to be accurate during intense physical exercise.

[09:54][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. So in terms of the tech out there currently, would it be safe to say that a lot of it’s either overestimating or underestimating based on these restrictions or are there devices or apps out there which have tackled this problem?

[Marco Altini]: So I think what we are starting to see a bit more is, for example in the context of even just monitors using, for example movement or steps, some of them are introducing something more around context. Which is important because when you use accelerometers this first instance were probably already in the late 70s, for sure in the early 80s.

The researchers started to develop the first equations to link accelerometer output and movement to energy expenditure. however some of the imitations there are that, for example, the relation between the accelerometer output and energy expenditure changes depending on the activity. So if you are walking or running there’s a different relation. If you are at rest, of course, there is no movement, and all of that.

Recently we started seeing even commercial devices which are able to detect activities. For example, I think the Basis watch is detecting a couple of activities. Even apps like the Moves app can detect activities.

So in general I would assume even though they don’t disclose the methods they use to estimate energy expenditure, I would assume the ones that are able to detect the activity, then what they do they use this table, it’s called the compendium of physical activities. Basically it’s a table where you have almost all possible activities you can think of, and for each of them there is a value of energy expenditure normalized by body weight that people are supposed to be expending while doing that activity.

So these devices are probably mapping the activity they recognize to this level of energy expenditure. This method [11:53 unclear] like four or five years ago, to be much better than using accelerometers without context. But it’s even better than combining heart rate and accelerometers, if you don’t take extra measures like modeling context or normalizing heart rate.

So just putting together accelerometers and heart rate is not able to outperform methods where you use only accelerometer data. But with a bit more of machine learning to be able to recognize what activity is being performed, and then map that to an energy expenditure level.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. It sounds like if you have the heart rate, and you have the anthropometric data ñ what’s your weight and age and so on — and if you have the accelerometer data showing the movement, and you have an algorithm which categorizes what kind of activity it is based on the accelerometer, what’s that showing.

Which, I know isn’t always correct, based on my experience. So sometimes, for instance, I was wearing the Basis and it would say I’m on a bike where I never got on a bike. So it isn’t quite perfect yet, but we’ll assume that’s getting better. And maybe it’s already better.

Then what they’re doing is they’re looking at the activity and they’re saying, ìWell for this type of activity this heart rate is standard for this kind of fitness, and this heart rate is standard for this kind of fitness.î Is that how it works? Or is it a more basic thing right now?

[Marco Altini]: I think step zero would be simply to map it to known values, regardless of your heart rate. Let’s say, an app without heart rate, like the Moves app. So you just have the activity type, and you map that energy expenditure. Yes, like the average energy expenditure for that activity for a person.

So you are walking, and of course you can walk at many different speeds, so maybe that’s not known by the app. But still you would assume that for the average walking speed for the average person, you would consume this many calories. And when you detect walking you just map it to that and then based on other characteristics you input, like your body weight, you scale that by your body size, basically.

And then if you do a bit of more advanced work, let’s say, and you want to develop your own model for a specific activity. Let’s say you have the Basis, and at Basis they have a couple more physiological parameters together with movement, then it could develop there on regression models by collecting reference data.

So normally we do that with indirect calorie measure. So that’s a device which is a physical mouthpiece, where you breathe and it’s measuring O2 and CO2 counts. So, you compare the O2 and CO2 in body sheets, and that’s basically energy expenditure. So by having people performing different activities wearing the Basis watch, while you measure these reference calorie meter data, then you can see how all these valuables change depending on the activity.

And then you can map, let’s say heart rate changes and movement changes, the energy expenditure for a specific activity. I don’t know if they are doing that, because that would require to do all the tests with a calorie meter. I would assume, considering that they have all that physiological data that they did also this kind of development. While maybe all the other devices which are simply accelerometers, they might have simply used the values from the compendium of physical activity.

Basically the compendium of physical activity is what you use also when you, let’s say you use an app for tracking your workout, like Runkeeper, that let’s you also manually enter the activity. So maybe one day you didn’t have your phone and you want to enter it manually, then it will also estimate your energy expenditure. And that’s basically just a lookup from this table. And then it’s just scaled by your body size and for the amount of time you did the exercise.

[15:49][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay great. So what we’re talking about here is physical activity level, right? These are different version of it. There’s energy expenditure, and there’s Steps, which is currently what’s on the market. All these devices are looking at quantifying our physical activity level.

I guess the question is is that what people really want in terms of the end game? Because you’ve got this app out which is trying to get at something which you feel is a bit closer to the end goal of what you want to measure.

[Marco Altini]: Yes, so while I was doing research here on energy expenditure and the more I looked close to the whole personalization story, basically I was thinking what is a way to quantify not only what activity you do, right, the amount of exercise, the Steps, but also what the impact of this activity on your health, if there is any.

So this is a process in which we try to move from quantifying physical behavior to quantifying physical activity related health markers. And one of these markers, which is probably the most important one, is cardiorespiratory fitness.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s kind of well-known. That’s been the standard for a long time, in terms of quantifying fitness. But it’s only been done in laboratory contexts, as I understand it.

[Marco Altini]: Exactly. So far, as you say, it’s been really, I think 20 or 30 years that we know for sure that all these studies show that low level of cardiorespiratory fitness is indicative of higher risk of getting different sort of diseases. And even in general of just what is called [17:24 check – all cause mortitus], so you’re just most likely to live less if you have a low level of fitness.

And what is interesting here is that it is true even when it’s basically controlled by physical activity or body size. So it means that it doesn’t matter even if you are obese or if you have less levels of activity, but as long as your cardiorespiratory fitness is higher, you tend to be protected with respect of these other issues.

And indeed we know that. The research community at least is well aware of the importance of cardiorespiratory fitness, but in the general population I think we still lack awareness of this. Mainly because, as you say, there are basically no tools. So the way this is measured is in laboratory conditions. The reference is called VO2 max test.

And while VO2 is the oxygen volume and this is called VO2 max basically because the way the test works is that you get people either to do a treadmill test or a biking test in which they bike around until exhaustion. So you increase the intensity of the exercise every 5 minutes or so. And basically there is a point in which an individual is still able to keep it going at that intensity, just a bit before you drop. And then your oxygen sort of plateaus, and that’s your VO2 max.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: What does that signify? Is that the moment when you switch to anaerobic, or what does it signify physiologically?

[Marco Altini]: Well, there is really the moment in which you cannot take any oxygen anymore. You need to stop. You cannot take any more intense activity, so that’s the max oxygen you can take.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So it’s like your maximum ability to metabolize…

[Marco Altini]: It’s the ability of your circulatory-respiratory system to provide oxygen to your muscles for sustaining exercise.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great.

[19:24] So showing that efficiency and when people are looking at that list, let’s talk a little bit about the decisions.

Typically when you have these meters when people are using these activity tracking meters for, whether it’s biking and running and so on, typically they want to improve something. They either want to lose weight, sometimes, or they want to improve their fitness. Or they want to improve their health.

So you’ve talked a little just there about cardiorespiratory fitness, we say that that has a protective effect against heart disease, which is one of the biggest killers. And also, if our cardio fitness is better, is more efficient, then we’re probably going to be able to run further, and run faster.

We’re going to be able to perform better, which is also something that we want. Whereas the Steps and the energy expenditure is hard to understand how that reflects either of those two cases, kind of like the use cases: health or better performance.

And with Steps and energy expenditure, you can tell that you’ve done more in terms of quantity but you can’t really tell if it’s going to give you more performance or you’ve actually got health benefits.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah.

So I think there is an opportunity in trying to quantify what is the fitness levels that you can have. You can have feedback for the ones that are interested just from a health point of view, to see if exercise is having any impact. You can have, actually even for professionals it would be, they do the VO2 max test and they know their actual cardiorespiratory fitness level, but still you cannot do that that often and it takes time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s expensive, I think it’s like 300 dollars or something. Because I looked up, when I was in the US recently I was going to do one in San Diego and they had a gym that was actually providing it. Sometimes you can go to laboratory health centers or sometimes some advanced gyms will have the equipment to do this.

[Marco Altini]: Yes. I think there are a few limitations around the VO2 max test, apart from the cost.

Certainly you need some medical supervision and you need, again, the calorie meter to measure the oxygen. It requires a level of infrastructure. And apart from that, I think sometimes it’s even tricky to interpret the result. Because VO2 max is normally reported normalized by body weight. So you need to provide people with an easier way to understand their fitness level.

So you have these tables where basically different levels are divided by gender and by age. So if you are a person of a certain age and you’re male, and then you have your VO2 max result and it would soon [21:53 unclear]. Okay?

But however, these tables are not organized by body weight. Only by gender and age, since the results are normalized. However, the exercise type you use to acquire the VO2 max data is not part of those tables. And that has a great influence on oxygen consumption.

Because even just when you normally measure energy expenditure, even if you’re doing an activity which is weight bearing, you literally carry your weight around, like when you walk around, then the link between oxygen consumption and body weight is much stronger compared to when you just bike. Especially for stationary biking in the gym your energy expenditure is much more similar to the one of a person which is of different body size compared to you. While if you would be walking or running there would be a much bigger difference, because it’s a different impact of body weight.

Even, like in one of my recent studies through my PhD I measured VO2 max on a group of 60-70 people, and for example there I had a subject which was unfit; so all the parameters that we measured seemed to show that his fitness level was quite poor. He had very high heart rate at rest, very high heart rate during all exercises, he couldn’t finished some of the protocols. During the free living part also, his physical activity level was very low.

And the VO2 max test [23:25 unclear audio] it turned a result that he was the most unfit person as well. However, if we go to normalize the VO2 max, so we divide by body weight, this guy became the second most fit of the entire data set just because he’s very thin.

And that’s actually the result normalized by body weight, is what you normally get. Because it’s common practice to report it that way. But at that point, how do you interpret it?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So it’s a bit tricky to make it. So VO2 max is the gold standard in terms of measuring this.

[Marco Altini]: Exactly, but it has its own limitations. Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: If someone was to go and take that test, what would you suggest they make sure, like to check they get a result that’s useful for them. Is there anything they can look out for or ask for?

[Marco Altini]: So in my opinion at this point, I tend to think that maybe a running test would be a better way to do it, because the relation with body weight is a bit more clear than compared to the biking test. However, normally a biking test is done also because of safety reasons. It’s a bit easier to do a maximal test on a bike; it’s a bit more of a controlled situation.

However, when you then go to normalize by body weight, the fact that your body weight doesn’t have the same impact because you’re biking and you’re not carrying your weight around, then you’re [going] to have this weird results like we did where the normalized VO2 max basically makes an unfit person the most fit person. That’s one of the reasons why I prefer to use VO2 max data non-normalized. So I use the value of oxygen consumption they reach, and that’s it. I don’t normalize it by body weight.

[25:13][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. So, are there benchmarks for that? If they get a specific score back they can assume they’re relatively fit?

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, but the problem with that [25:22 unclear] is then you don’t have this [25:23 unclear] they’re not aware of, that there are these tables for matching it to something like, [25:29 unclear], like fitness is poor or average or good. These tables are all normalized by body weight. So that’s sort of a problem.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So what you’re saying is if you were to do this twice, you could get your relative fitness without normalization, right? If I took a test today and I took another test in 6 months.

[Marco Altini]: Exactly. You could calculate longitudinally. That’s no problem, maybe it’s more difficult to compare with other people.

[25:54][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So is there any way we can get around the issue of normalization so that it works for us?

[Marco Altini]: There are some maximal tests which are not all bad.

So basically, some maximal tests, the way they work is that of course they want to predict VO2 max, and they rely on the fact that we know, as I was saying before, that the heart rate changes based on fitness.

So instead of doing a maximal test and measuring oxygen consumption until exhaustion, you do tests at a predefined speed. For example you run at a certain speed, you bike at a certain intensity, and then you measure your heart rate. And that goes into an equation that was developed before using referenced to VO2 max, which basically predicts your VO2 max based on your sub-maximal heart rate, and a bunch of other parameters like it measures your age and body weight and all these other parameters.

And the simplest of this test I actually did on [26:57 unclear audio] to measure heart rate, for example. I think something interesting is that we’re seeing now is also to bring awareness to people with [27:09-27:12 unclear audio] and we got this out from Stanford which is called MyHeart Counts, I believe.

So they measure, they ask you a lot of things and get a lot of reference points and your lifestyle and what you do. And then they track, using the phone, your activity. But since the study is all about cardiovascular health, they ask you to do this fitness test, which is one of the most commonly used because of its simplicity, I would say, where you just have to walk for six minutes.

And you have to time it, and you have to check the distance basically. So the longer the distance you go in six minutes, the more fit you are. And again, here you don’t need physiological data, and this might be probably a better test for people which are not in optimal health conditions.

But I think it’s good because the app is also targeting healthy users. So it’s a good indication that fitness should be of interest for the general population. And there is an effort here to raise awareness.

This being said, I think the potential of current technology is much higher. So you can do much better than that. And you can overcome also the limitations you had, because until now you had to either do a VO2 max test, which is expensive and has all the limitations you discussed, or even if you want to do a sub-maximal test you need still to go to a gym, you need to do an exercise at an exact intensity and then do your math to get what your VO2 max would be.

But right now, since we have phones with all sorts of sensors, and then we have wearable sensors and we have heart rate monitors and all of that, and then we have other reasons that can really automatically understand if you’re walking or running or what is your speed. You don’t even need a treadmill anymore to understand the context around the activity you’re doing.

So, some of the work we’ve been doing recently as part of our research is indeed to give people just a phone and a wearable sensor and don’t ask them to do any specific activity. They just live their life for two weeks while wearing the sensor.

And then all the other reasons we automatically understand: which location they are and what kind of activity they’re doing; if they’re walking, then then what is their speed. And then, basically you put your heart rate in a specific heart rate continuously. And by knowing that, since your heart rate still will be affected by your activity and your fitness, and you also rate the activity because you know the context. And then you can estimate the fitness level basically without requiring any test anymore.

So I think that’s quite interesting because you can finally get to something that is useable by everyone and doesn’t require any specific tests. And again, if you want to monitor them longitudinally, you don’t need to do a test every month. Because you just wear the sensor and it’s sort of being continuously updated just by wearing it.

[30:23][Damien Blenkinsopp]: So when you say longitudinally, that means testing ourselves in time, and seeing if we’ve got an improvement or decline over time.

[Marco Altini]: Exactly.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: See if what we’re doing is actually working or not.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah. To see if there is basically changes at the individual level.

[30:38][Damien Blenkinsopp]: So this is basically what your StayFit app does?

[Marco Altini]: So basically with this app, I tried to make something where you don’t even need the sensor anymore. So [30:48 unclear] yields a research prototypes. Basically it’s a necklace, you wear it and there is, essentially you get full SG. And then we [30:56 unclear] heart rate. Then there is an accelerometer which we use for activity recognition and walking speed. Then with the phone we use GPS to understand location of that.

However, even if now you have some trackers that do heart rate like the latest FitBit or the Basis, we don’t have access as developers to all of their raw data that you would need to develop algorithms on top of these devices. So what I was thinking is, well of course if you have heart rate data during all of these activities, your fitness estimate can be more accurate.

But, at the same time heart rate at rest has been shown to be linked to fitness. So the lower heart rate at rest the higher fitness. This was the case in many studies, even interventions about physical activity trying to increase physical activity, often show that they were also able to reduce heart rate at rest.

So what I did with this app was to combine the two aspects. So using just the phone you can get activity level based on the step count, which is on the phone, and this data is transformed in energy expenditure, and your physical activity level. And then you combine heart rate. And again since you need context, the way the app is used is by taking a short test in the morning, similar to what the HRV apps do.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, just to clarify, that means when you wake up in the morning you take a reading before you do anything else.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, exactly. So that’s the easiest way to isolate context without having to go through much trouble. You just, you wake up, you take your test, that’s at least the moment we are the least affected by all other parameters and stressors.

And then you get your heart rate at rest, which goes in the system together with a bunch of other parameters to get you an estimate of fitness. And what the app is actually estimating is basically your sub-maximal heart rate, which is then transformed to a number between zero and 100.

But the whole point here is that since sub-maximal tests basically measure your heart rate at a certain intensity, because that’s what then goes into the formula to estimate the VO2 max. But if you consider that your age, and gender, and body weight will stay pretty much the same if you do two tests in a short period of time, then the actual measure of fitness is just sub-maximal heart rate.

So your VO2 max will be different only if your sub-maximal heart rate is different. So, here I removed the VO2 max step and estimate directly their sub-maximal heart rate. Which is a proxy to fitness, basically.

[33:44][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. And how have you seen this work out? Because you’ve been using this app for a while, and I guess you’ve gathered some user data now as well?

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, I did. Not that much, I must say. So I cannot really make any analysis yet, especially because I don’t have a reference point either.

It’s more of an individual tool that you might want to use to track your fitness, but I don’t know the VO2 max of the people using it. So maybe it’s something for future versions would be to try to add some other reference points so that I can do some further analysis like I did with HRV apps.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. So in your own case, how long have you been using the app, and have you noticed any differences in your fitness? For example, your running time, because I know you’re a runner and you developed it primary because of that interest.

So have you noticed or seen differences in your fitness level, in terms of your efficiency and your performance, and seen those correlate within the app, or has it not?

[Marco Altini]: So I used it for about two months. Something interesting I think is around the metrics that I used. So for example, I used the physical activity level as a measure of activity. So the physical activity level is a normalized version of energy expenditure.

So if you’re telling me your energy expenditure today is 4000 kilocalories, I can’t really infer anything, because if you’re severely obese that may be just your energy expenditure at rest when you do an activity, right. At the other end, if you’re a thin person and a small person, then it means that you’re being very active.

So, the total energy expenditure is difficult to interpret without knowing who are we talking about. And the physical activity level is the energy expenditure divided by the basal metabolic rate, so the component result is your metabolism at rest.

In this case you would get a value which is representative of how much you move. So if you don’t move at all it’s one, and if you move a lot it really doesn’t get much beyond two. So that’s a good indication of physical activity.

And it’s based on energy expenditure, which I think is important because sometimes, for example, I could see in my data is that I went for a trip and I did a lot of hiking, which is a lot of activity but at the same time it’s not really cardio activity or activity that I believe would improve my fitness level. It’s not like when you go running you know the intervals on track.

It’s movement but I would assume my fitness stayed more or less constant those days, right? And if I look at Steps, I see that I’ve been much more active than my average, because you walk all day and it’s much more steps than when you go training. So if my fitness was just based on my activity, I would get theoretically more fit when walking on holiday.

However, since we use energy expenditure, the normalized energy expenditure, the physical activity level, that was pretty much the same as it was when I was here and I was training. Because the activity when I train here is much more intense and consumes much more energy than when you’re just walking. So I think that’s a valuable point of using physical activity level as energy expenditure to track fitness instead of just movement or steps.

[37:14][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. So for your hiking and so on, did you see your fitness level change in the app? Because it gives an index of one to 100.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, exactly. So it stayed pretty much the same.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So you saw basically that that case was shown in the results. Did you do anything where you saw your performance improve in your app and you correlated it to basically better times, or other things that seemed to be improving?

[Marco Altini]: For now I just saw it dropping, which is not good. So, yeah. I guess my condition is not ideal.

But I think it is interesting to track over long time. I tracked for two months, and I don’t race that often. Maybe for a professional person it would be more interesting because their life is training. For me it’s more of a hobby.

But I think looking after a year or so, then you can track it. You can look at data with respect to maybe the half marathons you did and the times you did, and then you get all these reference points, then it could be interesting.

So, you know I’ve been doing some work around HRV for example, and there it’s very valuable on a daily basis. Because there were points that you measure basically those points of this test, which can be training, and you get basically daily advice on how to train, and if your body is ready for another intense training. On the other hand this one tracks a parameter which changes much more slowly. Fitness doesn’t change fast.

[38:45][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right.

So this one strikes me as it would be more useful to understand the effectiveness of your program. Like, the protocols you’re using to increase your fitness, for the longer term? So a lot of people will follow a set program for a while, especially if you’re a professional athlete you’ll have a set workout and timing and everything.

So you can kind of evaluate the performance of that, and if it’s increasing in the fitness one. But as you said, because a lot of people are using the HRV today. We’ve looked at the HRV in the context of stress, of longevity, and also of course the training in terms of recovery, which you just mentioned.

So, I could imagine that some people might look a HRV and be thinking, “Oh, my HRV is higher so I’m fitter.” Right? Because we’re also looking over time rather than the day to day, looking at the trend. Would you say that’s the case? Or do you think that’s not an accurate way to look at HRV?

[Marco Altini]: I think HRV is great as a day to day tool for recording and a proxy to personal activity and it is true that even at the [39:47 unclear – professional] level, let’s say athletes tend to have higher HRV, and really sedentary people tend to have lower HRV.

But, the link between HRV and fitness is, let’s say far from being clear. Meaning that there have been many studies, and some of them found some link between HRV and fitness, meaning higher HRV higher fitness, but many many studies found no relation there. Especially when doing interventions.

So, you know, longitudinal studies where you take people through a training program and then you measure their HRV at the beginning and at the end. And many of these studies found that heart rate changed and it was lower, but they couldn’t find any change in HRV, so it might be that there is a stronger genetic component there.

And also physiologically speaking, with heart rate you train, so you train your heart which then would be basically able to pump more blood. The volume changes, increases per beat, and that’s why your heart rate also decreases. The more fit you get, you train your heart muscle, which is going to be able to pump more blood and oxygen to the muscles, and then your heart rate as a consequence also decreases.

However this link, in terms of HRV, I don’t think it’s clear. So in general, even in this study I was mentioning before where I had all these people doing VO2 max test and doing also all the free living recordings, that was not a longevity study, so we just got a snapshot of these people. But there we can see clearly there is a very strong relation between heart rate and their fitness level.

And this was true for heart rate at rest, heart rate while they were sleeping, heart rate during activities. So you always see this relation which becomes stronger, of course, for more intense activities, but is there already at rest. While with HRV we couldn’t see any link with VO2 max, even at rest or sleeping or anything. So, I think in general HRV might not be the ideal tool to monitor fitness level.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: In terms of cardio fitness?

[Marco Altini]: Yes, in terms of cardiorespiratory fitness. And basically as a proxy to VO2 max, heart rate at rest seems to be a much better parameter.

[42:28][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. If someone is just looking at their resting heart rate, that’s also a standard in athletics and so on, people could watch that. And then you’ve basically built up a bit more on that, through your fitness index.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah. So I basically used that one and the energy expenditure normalized value together with some adaptation due to age, so that basically the value doesn’t depend on age.

So if your other fitness index tries to predict is just maximal heart rate, basically it tries to predict, for example, what would be your heart rate if you were running, even though you’re now resting and you do these activities in your life. And then that your sub-maximal heart rate and your maximal heart rate are basically depending on your age as well, right. So it will decrease over time.

And so I applied some corrections there to allow people of different ages to get values that they could compare.

[43:26][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, right.

So it’s all about normalization, right? Getting normalization right so that you can use it, which would mean that you can compare it against different people. Right?

So just before this call, I was saying hey my score is 60, what it is it like? Does that mean I’m fit or not, compared to you, you’re 70 and I’m like, damn I’m less fit than you. Right? So that kind of context, which is literally what people like to do, right?

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, I think so.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: People want to be a bit competitive about this, and you know it’s part of team sports and so on. And people are into this stuff.

[Marco Altini]: Exactly. Because for every time if you look at VO2 max, for example, then it’s basically impossible to compare unless you have a person who is basically your age, your gender, and your body weight and possibly also your body fat. Then you can compare. Because otherwise there are too many parameters there.

[44:12][Damien Blenkinsopp]: So I wanted to use this as bit of a demonstration on what’s important in a biomarker if it’s going to be useful to us.

So one of the things you brought up, which is key here, is normalization so we can compare it to other people. There are different devices out there, but sometimes we can’t compare against other people effectively, because as you say it hasn’t been normalized. That’s one part.

What other things do you feel are important? Like if you just think of a biomarker, what would you be looking for to make it effective and useful to make decisions around?

[Marco Altini]: I think in general, it’s important that we always contextualize these things and this whole thing goes together with normalization. Normalizing parameters means also understanding in which context you were measured. So that’s something important.

Try to know everything around it and take care of taking measurements in isomeric conditions, because otherwise it’s easy to make the wrong conclusions just because some other factors are influencing what we are measuring.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s important to get some benchmarks.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So we can understand the implications for our goals. So I’d like to see in the future if you have more data with your fitness app to see if you can compare the range of readings for different users, and things like that.

[Marco Altini]: I think in general, when we make these tools and we release them, for me it’s very interesting to look and take it step by step.

First you try to look at some relations that have been proven already in research, for example with heart rate variability apps, I let the people give me some reference points. So basically they can annotate not only when they train, what’s the intensity of their training and in the next lessons they will be able to add some more text around sleep, and all of that.

And that’s interesting because afterward because then, again, you can put the whole heart rate variability story in context with respect to how they trained and all of that. And then you know from some studies in literature, on maybe 100 people, that there is an important relation between HRV and training.

But then you can just scale that at the level of 1000 people and you start to find all of these relations. And then you can start exploring maybe a new one. So I think that’s quite powerful.

[46:37][Damien Blenkinsopp]: So another thing about this measure and measures that tend to be more useful is its stability. We’ve often come back to this in our podcast in different episodes, with different markers, whether it’s laboratory testing or whatever.

If a marker is moving around a lot ñ HRV is kind of moving around a lot, which can make it more difficult to use sometimes.

So, often you’ll see a pattern where one day it’s up and a little bit down the next day. It’s always kind of a jagged reading, so you have to kind of take an average of the last three days and things like that to get a stable reading on where your recovery is. Of course where there are the extremes and it really drops, then you’re like, “Okay this is a recovery day.”

But the thing about these biomarkers in general is it does help if they’re more stable and they’re moving along more steadily over time so you can make decisions on a more even basis. Because we’re not making decisions hour by hour in these cases where it’s fitness and health. It’s more like what am I doing this week versus next week, and so on.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, the two cases also something with HRV, I think it’s very powerful because of that, because it can react that way to some stressors. But at the same time, it makes it very difficult to interpret sometimes. Because even consecutive tests can have very different values.

So that makes it quite difficult sometimes. But yeah. With heart rate, that’s a bit less the case. So indeed that’s one other reason why heart rate at rest is better for the cardiorespiratory fitness estimate, because it’s more of a stable parameter like cardiorespiratory fitness is. While HRV is very good as a parameter which you can use to understand how you’re reacting to certain stressors.

[48:22][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, that’s great. So different contexts. So I also know that you’re now working with data to help mothers with pregnancy.

[Marco Altini]: True.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So I wanted to touch on that and see what you’re doing there, because it’s an interesting area.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah. Well basically I’m working at the start-up at Bloom Technologies, where we are working on different aspects and the goal is to better understand pregnancy complications, by monitoring longitudinally different physiological parameters.

Since many of these complications, like for example pre-term birth, or gestational hypertension or gestational diabetes, are poorly understand, let’s say. And even in the developed world, even in the US, the percentage of pre-term birth is more than 11 percent and the whole medical community is, let’s say a bit struggling around how to try to bring this epidemic down.

So what we are doing there is to try to add some parameters to what we are measuring today. For example, uterine activity or even heart rate variability over time. And all we discuss now basically becomes important again because during pregnancy there are even more challenges because all these parameters change also because of pregnancy.

For example, heart rate increases by, let’s say, 10-20 beats during pregnancy because of course their heart needs to work harder because it needs to provide also for the fetus while it’s growing. So you have the additional context of knowing at which stage you are of the pregnancy, and trying to understand how all these parameters change.

So what we hope there is to be able to use this physiological data contextualized longitudinally over time, and try to get a better understanding of what is the impact, for example, of uterine activity and physiological stress, physical activity in all of these complications together with the variables which are already known to be affecting pregnancy.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So it strikes me this could be pretty interesting, because you might be able to alert someone to an issue over pregnancy. What kind of outcomes do you expect once this work is completed? What kind of goals would you have?

[Marco Altini]: So I think the first part would be to try to understand better what parameters are influencing some of these complications. And then for some of them there are interventions.

If you consider hypertension or diabetes, you can reduce activity or [51:02 unclear] and you need to know to be a bit more under control. Others are more complicated, for example pre-term birth; there is really no intervention there.

So still by understanding better what are the pathways there, and what is causing the issue, you could then after the second step try to see what is possible to do in terms of, for example, behavioral changes.

It is, for example, known that high stress has an influence on some pre-term birth rate, and on pregnancy outcomes in general. So if you can measure physiological stress, you could also have an intervention around some mediation practice or whatever it is that could lower stress, and then try to reduce complications around pregnancy with these kind of feedback loops.

[51:54][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great, thank you.

I’m guessing it’s quite a ways off in terms of bringing something to market or things like that.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah we hope to have a product by the end of the year, around contractions. But again, let’s say more limited but at the same time that would allow us to collect data and work with hospitals and doctors to start to explore a bit more around this using also the power of having consumers with the device.

And consumer inserted data and data sets can grow much faster than with regular clinical studies while still providing clinically accurate data. So, we’ll be looking into that with some collaborations also here, for example with UCSF in San Francisco where they have a pre-term birth initiative that we are collaborating with.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great thanks.

[52:50] So, where should someone look first to learn more about the topics we’ve talked about, VO2 max, or are there any presentations on cardio fitness or anything like that you know of, or maybe a book, that if someone was interested in this to get a better idea of this they could look up?

[Marco Altini]: There are some good resources, maybe I’ll just provide you some links. More on the physiological aspects. I think in general I’m happy to see the whole thing moving forward with this Stanford study.

So even just the website of this study, the MyHeart Counts study would be a good starting point to understand better these things. Because indeed we target as well healthy people. So giving a look at this up, it would be a good starting point for your cardiovascular health.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, we’ll put those in the show notes then.

[53:36] What are the best ways for people to connect with you, and to learn more about what you’re up to?

[Marco Altini]: I would say through my website. I try to keep it updated. Normally I’m very active. So if they just drop me a line or an email or something, I’ll get back to them for sure.

[53:52][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Is there anyone besides yourself you’d recommend to learn about cardio fitness and these area we’ve been talking about today?

[Marco Altini]: From the HRV stories, for sure all the people you had already on your show are great experts. For the fitness, I would need to think about it, because the research I’m doing, being a researcher now it means it’s going to take some time before it’s out. So I’m sure there are a couple of other groups that are doing great work there, but I haven’t seen much yet.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. Well we’ll be linking to your stuff in the show notes of course, so people can check that out.

[Marco Altini]: Maybe I’ll think of something and I’ll get back to you on that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, thanks.

[54:34] I’d also like to learn a bit more about your personal approach to body data. Do you track any metrics or biomarkers for your body on a routine basis, whether they be labs, and so on.

I know currently you’re using your own fitness index, correct? What are you doing in your life, or what have you been doing over the last year?

[Marco Altini]: So basically I’ve much of a maker approach. I use this stuff all the time when I make it because I want to try things first and it helps me understand the limitations a lot and where things can improve. So I’ve been using HRV for a long [time] because I have these apps around HRV and now I’m using also these ones about fitness.

In general, the only things I really track are my trainings. So I like to track that and see improvements there. And that’s why I also work around these variables which are connected to activity and fitness, and try to basically close the feedback loop, like with HRV, that gives you advice, and fitness that tries to quantify what your basically current level, what performance can you achieve.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great thanks.

[55:45] Have you got any insights, like from the data you’ve collected, have you got an insights about your biology? Have you made any changes to behavior, or taken some kind of actions?

[Marco Altini]: No. I haven’t yet. It’s not that I didn’t get any insights, but I think it’s important to track first for very long periods. Meaning a year at least before you can start making changes.

Because so many other parameters affect our physiology and performance, especially if I consider training there are months where everything looks the same. Like maybe I haven’t traveled much, and I kept my diet the same, and my stress at work is pretty much the same. And I think I haven’t over-trained, but still there are some weeks where you don’t perform very well.

So it would be sometimes easy to make the wrong conclusions if you tend to make too many changes. So I think it’s good to track for very long periods, even HRV, to get all the values you see. And then you look afterward how your training had an impact and all of that. And then you try to make adjustments.

Maybe around HRV I am making adjustments, like I tend to follow now what I see there. You find something very interesting things, like sometimes you can spot you are sick before you actually realize you are sick. You do your test in bed because your HRV is like…hugely affected by that, for example like even just a fever or something.

Maybe in the morning you don’t just feel particularly well, but it seems just a regular day. And then your HRV is terribly low, and then the day after you’re sick. And that’s quite interesting to see.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I definitely rely on it. I’ve seen that a number of times. If it really drops, then I’m like, “Uh oh.î I’m going to get some vitamins, liposomal vitamin C and stuff like that to try and void the crash the next day. Or minimize it a bit. So I think it is pretty useful like that.

[Marco Altini]: Yeah, it’s quite interesting.

[57:41][Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay, so what would you number one recommendation for someone trying to use data to make better decisions about their health or performance or longevity?

[Marco Altini]: Be consistent. Don’t expect short term miracles but keep doing it, keep tracking. Try to understand at your personal individual level what is affecting these variables and then slowly start to make changes and bring to mind how these changes affect the rest. Let it be, I don’t know, performance or whatever variable that matters to you.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, I think you make a great point because as you were saying, there are so many different variables which we can’t keep track of. Especially in our busy lifestyles today. Whether it’s travel, a different location, different food, different sleep conditions, or maybe just different supplements and other things if we’re experimenting things. There are a lot of different variables that can influence it. So that makes a lot of sense.

So Marco thank you so much for your time today. It’s been a great chat.

[Marco Altini]: Thank you Damien.