Can you get similar beneficial results from a nutritional supplement as you can from a water fast (previously discussed in episode 16 and episode 28)? Oxaloacetate supplements (also discussed in this episode with Bob Troia) are currently being studied for their use in improving blood sugar regulation and potential anti-aging properties.

– Alan Cash

Alan Cash is a physicist who has spent years researching the effects of oxaloacetate. Through his efforts and travels he has seen great success for terminally ill patients and more who use oxaloacetate to supplement their health. Cash helped stabilize the molecule so that it could be used as a nutritional supplement and continues to advocate and study its use so that more research and clinical trials can continue to support its use.

In this interview we get into the nuts and bolts of how oxaloacetate works, the current studies underway, and some different ways you can use it depending on what benefits you are seeking.

The episode highlights, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

What You’ll Learn

- The implementation of a calorie restriction diet may work to consistently increase your lifespan and reduce any age related diseases (6:19).

- Calorie restriction seems to affect the energy pathway of the cell (9:20).

- We can essentially “bio-hack” our systems by tricking the cells into thinking that the NAD to NADH ratio is high so that fat production is reduced (12:50).

- Human trials have shown that calorie restriction reduces fasting glucose levels and atherosclerosis (13:46).

- Reducing age related diseases will increase the average lifespan and increase the maximum lifespan for every cell in the body (14:32).

- Oxaloacetate is an important metabolite involved in one of the energy pathways in the mitochondria, the power house of a cell (16:20).

- Oxaloacetate is used in the Kreb’s cycle to oxidize NADH to NAD (17:09).

- A human clinical trial in the 60’s demonstrated that the use of oxaloacetate as a nutritional supplement reduced Type 2 Diabetes symptoms (20:00).

- As the dosage increases from the minimum 100 mg other system processes occur, such as the reduction of high glutamate levels, which is one of the damaging factors for closed head injury/stroke victims (22:33).

- A medical food called CRONaxal contains a large dose of oxaloacetate which, when used in conjunction with chemotherapy, can reduce tumor size and sometimes stop tumor growth completely in patients with brain cancer (26:07).

- Fasting/a calorie restricted diet is another technique that has been shown to slow brain tumor growth (27:53).

- Some cancer patients have already seen results with oxaloacetate supplementation and calorie restriction diets, however these are just individual cases and not clinical trials (28:46).

- Recently, clinical trials have begun to study oxaloacetate as a treatment for different conditions such as mitochondrial dysfunction, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease (30:13).

- Oxaloacetate may also work well to reduce inflammation and increase neurogenesis in the brain (32:30).

- Oxaloacetate may also become an important supplement for athletes who encounter severe head injuries during their sport (34:30).

- Long term potentiation, the restoration of the ability to learn, may improve for patients after a stroke or closed head injury if oxaloacetate is used in combination with acetyl-l-carnitine (36:18).

- Alan Cash spent years proving to the FDA that there do not seem to be any negative effects found with taking large doses of oxaloacetate (38:35).

- So overall, oxaloacetate has an immediate pharmacological effect on the glutamate in the brain and a long term genomic effect on the mitochondria (46:30).

- When trying your own experiment, take a daily fasting glucose level for a couple weeks to see the normal variability and then follow with oxaloacetate supplementation along with daily reading of your glucose levels (48:06).

- The biomarkers Alan Cash tracks on a routine basis to monitor and improve his health, longevity and performance (55:29)

- Alan Cash’s one biggest recommendation on using body data to improve your health, longevity and performance (58:49).

Alan Cash

- Terra Biological: Alan Cash’s company which produces the stable form of oxaloacetate.

- Oxaloacetate supplementation increases lifespan of C. elegans: The original study published by Alan Cash on PubMed.

- : you can contact Alan Cash with questions using this email address.

Tools & Tactics

Supplements & Drugs

Oxaloacetate is available in a few versions in the market today – all of these come from Alan Cash’s company since he developed the proprietary method to thermally stabilize it and as such make it usable. A number of studies on Oxaloacetate were mentioned in this interview – see the complete PubMed list here.

- benaGene Oxaloacetate: The nutritional supplement (100mg) version of Oxaloacetate to promote longevity and glucose regulation.

- CRONaxal Oxaloacetate: This version of oxaloacetate is a medical food (containing oxaloacetate) which, when used with other treatments such as chemotherapy, has been shown to significantly improve outcomes and quality of life for cancer patients.

- Aging Formula Oxaloacetate: Dave Asprey’s supplement is the same as the benaGene version of Oxaloacetate.

- Acetyl-l-Carnitine: Mentioned with respect to a study where a combination of oxaloacetate and acetyl-l-carnitine reduced long term potentiation impairment in rats.

- Metformin: A drug which is used to improve blood sugar regulation in diabetes. Researchers are looking at its wider applications as a knock on effect from improving blood sugar regulation to cancer and aging.

Diet & Nutrition

- Calorie restriction: this dietary regimen involves a significant decrease in daily calorie intake and has been shown to slow the aging process as described in this review article. You can learn more about the potential benefits and the arguments against the anti-aging benefits of calorie restriction in episode 14 with Aubrey De Grey.

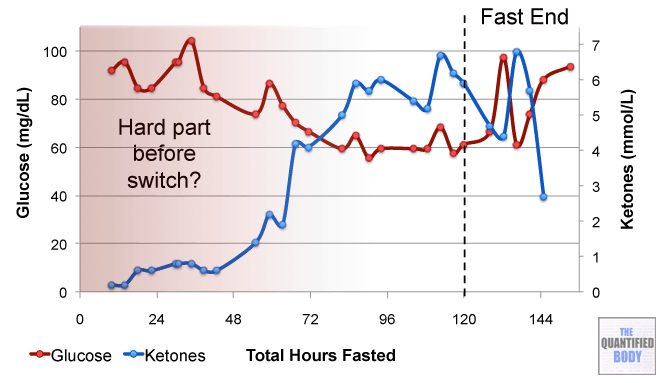

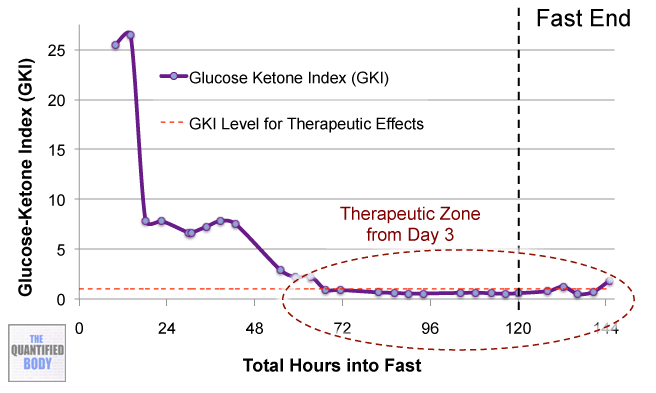

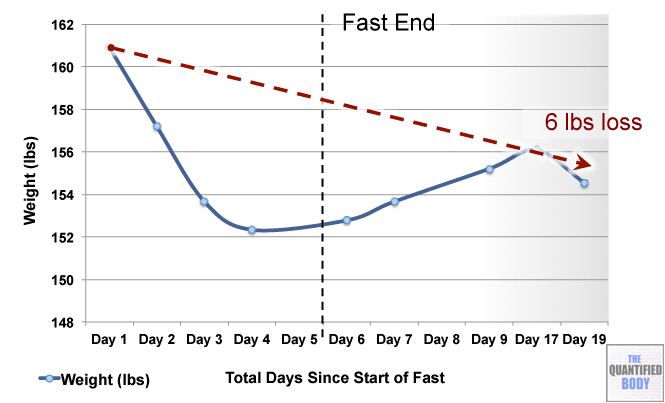

- Fasting: The fasts referred to in this episode were complete water fasts that were also being used in combination with oxaloacetate in order to attempt to “stack” the effects and get better outcomes. The examples given were case studies of cancer patients (no clinical trials have been completed as yet). For more information on fasting as a possible cancer treatment see episode 16, and episode 28 on our water fasting self-experiment.

- Calorie Restricted Ketogenic Diets: In a similar light to above, the anecdotal cases discussed for cancer were patients use of ketogenic diets (that put you into ketone metabolism, by restricting carbs and protein, and emphasizing fat) which were also calorie restricted. This involves stacking two nutritional strategies: ketogenic diets have been shown to be therapeutic for some conditions like alzheimers and blood sugar regulation related problems as has calorie restriction in general. Then some of these cases were also combining the use of oxaloacetate, again to try to stack the effects from these three tactics to further improve outcomes. See episode 7 for complete details on using ketogenic diets as a tactic to improve health.

Tracking

Biomarkers

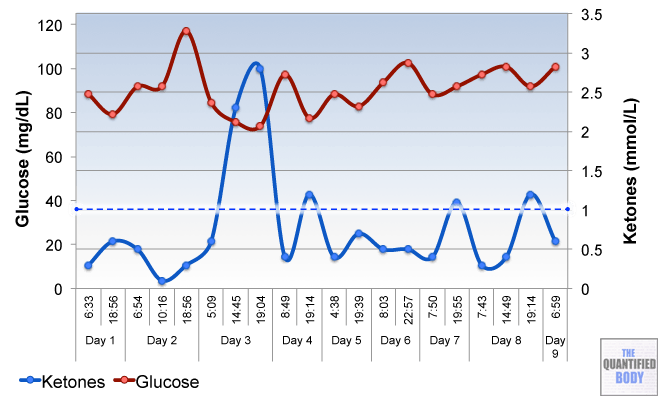

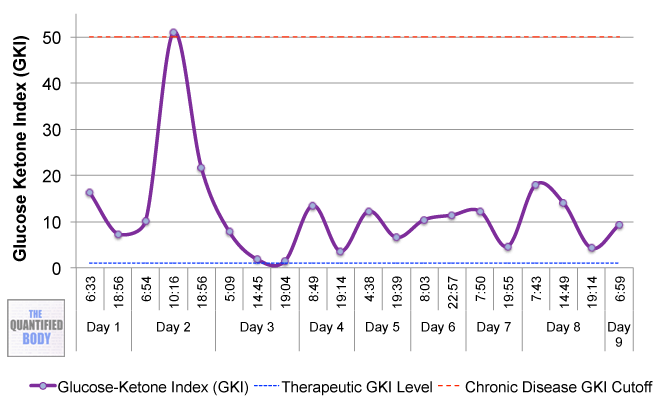

- Blood Glucose Levels (mg/dL): A measure of the level of glucose in the blood at one point in time. Fasting blood glucose levels are specifically taken when you have not eaten for at least 8 hours and optimally would be between 75 and 85 mg/dL. Health concerns with blood sugar regulation such as diabetes risk start to rise over 92 mg/dL. After taking oxaloacetate for many weeks Alan Cash suggests that your fasting blood glucose should vary less when compared with any control levels. These levels can be measured at home using a glucose monitor and glucose testing strips (an explanation for the use of glucose monitors can be found in this episode).

Other People, Books & Resources

People

- Hans Adolf Krebs: Krebs is best known for his discovery of the citric acid cycle, or Kreb’s cycle, which is the main energy pathway of a cell.

- Dominic D’Agostino: Well known for his work with ketogenic diets and performance.

Organizations

- Calorie Restriction Society: This organization is dedicated to the understanding of the calorie restriction diet by researching, advocating, and promoting the diet through regular conferences, research studies, and forums.

Other

- Kreb’s Cycle: oxaloacetate is one of the components involved in this energy pathway in the mitochondria of a cell.

- NAD/NADH: the effects of oxaloacetate in the Kreb’s cycle changes the ratio of NAD and NADH in the mitochondria which in turn affects the energy available to the cell.

- Orphan Drug Act: This law passed in the US in 1983 has provided more opportunities for researchers and physicians to pursue drug development for rare, or “orphan”, disorders.

- Calorie restriction PubMed results

Full Interview Transcript

[Damien Blenkinsopp]:Alan, thank you so much for joining the show today.

[Alan Cash]: Oh, thanks. It’s always a thrill to talk about oxaloacetate.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: First of all, I’d just like to get a bit of background story as to why you got interested in this at first. What’s the story, basically, behind how you got interested in oxaloacetate, and started getting involved with it?

[Alan Cash]: That’s a pretty weird story.

It turns out I had a brain condition where nerves sometimes grow very close to arteries. I had an artery that wrapped around my nerve. Every time my heart beat it acted like a little saw and eventually cut in through the myelin sheath that surrounds the nerve and protects the nerve, and went directly into a nerve bundle that was a major nerve bundle in my neck. And the result was instantaneous pain.

I found out that I was very lucky; I was able to get it corrected. They just went into the back of my head and followed the nerve until they could find where it crossed over, and they untangled it and put in a piece of Teflon. So now I don’t stick, but the pain is 100% gone, which is really nice. A miracle of modern science, because it was pretty terrible.

In looking up this condition, I found that it was really a condition of aging. As we grow older, your arteries get about 10 to 15 percent longer, even though we’re not getting 10 to 15 percent longer. So they have to fold over, go someplace, and it was just bad luck that it folded over next to this nerve.

As a physicist I thought I’d look into aging and see, whats the current state of what we can do about aging. And thankfully at that time there was a lot going on with the basic fundamentals of aging and trying to understand this, and looking at all the data that’s out there. That’s what physicists do; we take a huge amount of data and see where the kernels of truth are. We try to think of E=MC2, or F=MA, how much that describes about the universe.

And looking at the aging literature, the thing that stood out the most is almost nothing works, which is disappointing. The one thing we did find that worked consistently throughout the animal kingdom was calorie restriction. That was discovered back in 1934 in Cornell University.

It’s not just the diet. It’s essentially establishing a baseline of what you’d eat if you had all the food available, and then backing off that baseline anywhere from 25 to 40 percent. And when you do that consistently over a long period of time, we see several things. One, we see an increase in lifespan. Not just average lifespan of the group, but the maximal lifespan is also increased.

For small animals that live short times, that could be anywhere from 25 to 50 percent increases. In primates, we’ve seen an increase in lifespan of about 10 to 18 percent, depending upon the test. So we’re thinking in humans, we’ll probably see something in that range if you calorie restrict your whole life.

The other things we see though are a reduction in age related diseases, such as cancer. Our animal models indicate that incidence of cancer is 55 percent less in animals that calorie restrict. And that’s one of the most effective methods we have of preventing cancer, that we know of.

Incidence of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s are either reduced or greatly delayed. Incidences of any kind of autoimmune type issue, or inflammation issues. So it’s very, very powerful this concept of calorie restriction, and it wasn’t until just recently that we figured out molecular pathways of why it’s working.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, in terms of the actual mechanisms for what’s going on in the body when we calorie restrict, what happens? What is it that creates these benefits and these changes in our biology, versus disease, and longevity in general?

[Alan Cash]: We’ve been looking at that for a long time as a question, and some of the things that we looked at were does it matter if it’s the calorie restriction with fats, or does it matter if it’s just carbohydrates or proteins. And what we’ve seen is it’s pretty much across the board ‘calories’.

There are various diets out there – there’s a new diet every week it seems like – that looks at restricting one form or another of calories, or fats, or proteins, or even specific components of proteins. But what we’ve seen in general in calorie restriction is it’s the number of calories.

So, based on that it seems like it’s an energy proposition, and looking at the energy pathways there’s been focus on the ratio of two compounds that are pretty much the same. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, or NAD, and it’s reduced version NADH. So that ratio, which is also known as the redox of the cell, is looking at the energy of the cell. And when we have a very high NAD to NADH ratio, we see effects very similar to calorie restriction.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So in terms of what that’s actually doing, do we understand why the changes in NADH create this change in our biology?

[Alan Cash]: You know we’ve been able to trace this, and what we see is increasing the NAD to NADH ratio – and you can do that through a variety of ways – but that increase is measured by a protein called AMP protein-activated kinase, or AMPK. What AMPK does is it monitors, essentially, the NAD and NADH ratio, or the redox of the cell.

Think of it as a see-saw, so with AMPK as the fulcrum of the see-saw and NAD on one side and NADH on the other side. When the see-saw is in one position, AMPK will then act with other proteins that translate to the nucleus and turn on genes. When the see-saw is in a different position, AMPK will work with other proteins that translate to the nucleus and turn on different genes.

So let me give you a specific example. If you’ve had a lot to eat, your NAD to NADH ratio will be low. And AMPK will turn on genes that help with fat storage and production, because you’ve got all this extra energy, so hey let’s store some of it. So it will actually start producing proteins that deal with fat storage and synthesis.

On the other hand, if the see-saw is in the different position, if you haven’t had a lot to eat, there’s no point in storing fat. And so your genes will not be making these proteins that assist in making fat production. So how can we use that information?

For instance, when we trick the cells into thinking that the NAD to NADH ratio is high – or that the animal hasn’t had a lot to eat even if it has – we can slow down the rate of fat production, which could be interesting for people on diets. What we see is that you still gain some fat, but you just don’t gain it as fast.

So, biochemically, there are reasons why when you go on a diet and you lose all that weight, and you stop the diet and you rebound back very quickly. We can slow down the rate of rebound if we can keep the NAD to NADH ratio up high, because then the genes that are produced that create and store fat aren’t being produced. So there’s some really neat tricks that we can use to bio-hack into our systems that are existing systems.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, yeah. There are quite a few potential benefits to calorie restriction. We’ve come across some of these before. We’ve spoken with Dr. Thomas Seyfried about purposefully doing fasting for this kind of work as well.

What are kind of list the main big areas which people have seen this impact, like diabetes. What have you seen in your area, areas where people are meaningfully impacting this area with calorific restriction?

[Alan Cash]: We’ve actually done human trials in calorie restriction, and what we see is a reduction in fasting glucose levels. We also see a reduction in atherosclerosis, which, considering heart disease is the number one killer in America, if we can reduce that you’re going to have people living longer. That alone is huge.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So that just begs the question, when people are doing these estimates of longevity, is it because you’re reducing the risk of many of the kind of diseases that kill us – like cancer and neurological disorders, and heart disease – that people are living longer, and therefore you’re getting a higher longevity score? Or are they kind of separate topics?

[Alan Cash]: It’s both, actually.

Reducing these diseases is going to bring up the average increase in survival. So that would give you your average increase in lifespan. But there are certain people who don’t get these diseases, and they live a long time. But calorie restriction has been able to increase the maximal amount of lifespan. So that’s making every cell in your body live longer.

And we see that in our animal tests. For instance we started off working with these little worms called C elegans, which are used a lot in research because we understand, somewhat, the genetics of them. And one of the interesting things about these worms is once they go into adulthood, they don’t produce any more cells. That’s it.

They only live for about 30 days, but they live with the cells that they have. So if we can extend their lifespan, it means that we’re allowing each of their cells to live longer, and to be functional for longer. And when we increase the NAD to NADH ratio in C elegens, we see up to a 50 percent increase in lifespan.

So, as I said, it’s both. It’s eliminating a lot of these diseases that are associated with aging. I mean, think of all the diseases that you get when your old that you don’t get when you’re seven years old.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, I’m sure you’re aware of Aubrey de Grey? We had him on the podcast previously talking about his seven areas of aging, which are basically diseases of aging. So he’s looking at it from that perspective. So, in terms of oxaloacetate, which is the mechanism you were using to generate that, where does it actually come from? What is it?

[Alan Cash]: Well, it’s a human metabolite. It’s in something called the Krebs cycle, which is what gives us power in our little mitochondria. So, mitochondria can be thought of like a little power plant. Glucose is the fuel for the power plant.

So the more mitochondria you have, the more power plants you have, but you have to also have the fuel, the glucose, to up-regulate that. So oxaloacetate is one of those critical components within the mitochondria. So it’s in every cell of your body already.

Now, when we give it to animals, the reason we started looking at oxaloacetate is in looking at our energy pathways, oxaloacetate can break down into malate, which is another metabolite. It’s found in excess in apples. And as part of that reaction, it takes NADH and turns it into NAD.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So it takes it from reduced into the oxidized form?

[Alan Cash]: Yes, and so in doing that, because you’re taking something from the denominator and putting it in the numerator, it changes the ratio very rapidly. The first person who measured this ratio change was Krebs himself, back in the 60’s. He added oxaloacetate to the cells and he saw a 900 percent increase in the NAD to NADH ratio in two minutes. So, huge changes with this human metabolite oxaloacetate.

Now, oxaloacetate has got some problems. It’s not very stable, it’s highly energetic. Commercially it’s available through chemical suppliers, but you have to store it at -20 degrees Celsius. If you want to make popsicles out of it, you could probably do that. But putting it into a usable supplement has been very difficult, and that’s why you don’t see it very often.

We came up with a method to thermally stabilize it so that it can be stored at room temperature for a period of up to two years without degrading. And that’s how we were able to introduce this into the market.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. So, in terms of where it comes from, in my understanding it’s also something that is part of foods. So there are foods which have oxaloacetate in it, so it’s basically a nutrient that’s found in the environment?

[Alan Cash]: Yes. Absolutely. Although it’s only found in very, very small amounts. There are some foods that have higher amounts of oxaloacetate, and these are foods that typically have higher amounts of mitochondria.

So, for example, pigeon breast has a lot of oxaloacetate in it because you need tremendous amounts of mitochondria to power flight. That’s what one of the most energy intensive things out there, is flying around. But you need about 18 to 20 pigeons breast to get the amount of oxaloacetate that we see as the minimum for seeing some of the gene expression changes we want to accomplish. So it takes a lot of pigeons.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you’ve determined the minimum effective dose, which is around how much?

[Alan Cash]: So far – and this is from a human clinical trial – one of the side effects of calorie restriction in primates is it eliminates Type 2 diabetes, which is a good thing. And it turns out they, in trying to mimic calorie restriction – which is what we’re trying to do is turn on the same molecular pathways – we looked at oxaloacetate, and there was a clinical trial that was done back in the 60’s in Japan.

This was published, and it showed that oxaloacetate reduced fasting glucose levels in diabetics. So, we knew that this is one of the side effects of the calorie restricted metabolic state, and we could look at, in humans, what is the most effective dose.

And what we found is they did a range in this clinical trial of 100mg to 1000mg. There were no side effects in the 45 day trial. 100 percent of the people saw a reduction in their fasting glucose levels, which was good because they were all diabetics. We couldn’t understand why this wasn’t commercialized back in the 60’s.

So I actually flew to Japan to interview the department that was responsible for this clinical trial. The conversation went something like this, “Hi. I’m Alan Cash, your department produced this paper on oxaloacetate working in diabetics to reduce fasting glucose levels. Where’s the follow-on work?”

They said, “Well there is no follow-on work.” And I said, “Well why not?” They said, “Well because it’s a natural ingredient.” And I said, “Yeah it’s not only natural, it’s a human ingredient. So toxicity is extremely low.” And they said, “Yes, but we can’t get a patent on it.” And that was pretty much the end of the conversation.

So, as far as knowing the dosing and what’s effective, we already have a clinical trial showing where the minimum effect is, which is 100mg, which is where we set our sights to put out a nutritional supplement.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

So, was there any advantage for the people, if we take the most extreme example, the people taking 1000mg in that study, was there any advantage to it? Did it impact blood sugar regulation differently?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, well actually, as the dosage increases, we start looking at other reactions that oxaloacetate are involved in. And one of the main other reactions is the combination of oxaloacetate with glutamate. So, oxaloacetate and glutamate link together and that reduces glutamate levels in the brain.

Now that can be important for certain people. For instance, in a closed head injury, 20 percent of the damage to your brain is caused by the actual strike to the head, the damage to the tissue. 80 percent of the damage is caused by the aftereffects. And those after effects are in your brain it releases something called a glutamate storm.

Glutamate is one of those essential brain chemicals that you need to function properly, but if you get too much of it it excites the neurons to the point where they die. So this glutamate storm is responsible for about 80 percent of the damage.

And what they’ve been able to show now with oxaloacetate is primarily in tests over in Europe – the Weizmann institute out of Israel is doing a lot of this work, and there’s also some people in Hungary and Spain that are doing quite a bit of work with oxaloacetate. But they’re able to show that oxaloacetate, if you can get it to a stroke victim or a closed head injury victim within two hours, 80 percent of the damage is eliminated.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow. What, do they just take a small dose, or what does it have to be?

[Alan Cash]: No, you’ve got to take a lot, because you have to get it into your bloodstream, and if you take, let’s say, two 100mg capsules of oxaloacetate we’ve seen the data in the bloodsteam, only about five percent gets through. The rest of it is used up in the liver and intestines. That’s not a bad thing, because you want to keep those things healthy. But to get it so that it starts reducing glutamate levels in the brain you want to increase it’s supply in the bloodstream, and so you’ve got to take a lot.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, basically after that is it always five percent? If I take 1000mg, is it just going to be 15mg?

[Alan Cash]: We don’t know. There may be a point where you start overloading the liver and more passes through. I can tell you that we have a medical food that is directed towards people with brain cancer, because if we can reduce the glutamate levels in the brain we see better results.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Because people, just to get back to it, is it that people with brain cancer tend to die from glutamate toxicity? Is that one of the main mechanism for their death? Or is it acting on other dimensions?

[Alan Cash]: Well, one of the main predictors of survival is the amount of glutamate that’s produced because what the tumor does is it produces tremendous amounts of glutamate, and it kills the surrounding tissues so that the tumor can grow into that area. So, if you can stop that, you don’t kill the tumor, you just stop it growing.

And this is essentially what we’re seeing with the product called CRONaxal, which is a medical food [that] is a high, high dosage oxaloacetate. So you may take the equivalent of 30 to 60 capsules of the nutritional supplement per day, and we’re seeing in animal tests a 237 percent increase in survival.

So FDA gave us an Orphan Drug designation for oxaloacetate for brain cancer. In the actual human work, we’re just doing case studies right now, but in the 17 case studies that we have MRI data on, the oxaloacetate was in conjunction with chemotherapy. So you use them together, it was able to stop tumor growth, or reduce tumor size, in 88 percent of those patients.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow, so that’s pretty great statistics there.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, considering some of these people with glioblastoma, their tumors were growing at a rate of 80 percent per month. You can do the math there, it’s not a great equation.

And we were able to bring that growth rate to, in one guy’s case – he was 42 years old, two kids, a nice guy – we were able to bring that growth rate to zero for eight months. That’s very significant when chemotherapy alone only increases survival by a month and a half.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow, right. So, you were also saying earlier, we were just discussing you looking at combining oxaloacetate with fasting. We spoke to Dr. Thomas Seyfried about this recently, and you may be seeing potentially better results with that? Or it might be–

[Alan Cash]: Well what we’ve seen so far, fasting is one of the techniques used in brain cancer to slow or retard the growth of the tumor. It’s one of the few things that has been shown to work, especially a calorie restricted ketogenic diet, where you eat more fats.

And the thinking behind that is that you reduce glucose levels tremendously with the ketogenic diet, and glucose is one of the things that feed the tumor. Now, the other thing that feeds the tumor, according to Dr. Seyfried, could be glutamate. And so if we can reduce glutamate levels also with oxaloacetate, we may see some impressive results.

And we’re already starting to see that in anecdotal cases in patients. We had one young man who had a slow growing brain tumor that’s been able to stop it’s growth with a combination of calorie restriction and oxaloacetate supplementation with our CRONaxal product for a period of two years now.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow. And so is he taking around 6000…

[Alan Cash]: No, his tumor is slower growing, so he’s taking about the equivalent of 10 capsules a day.

We’ve also had recently a woman with Stage 4 breast cancer. Her latest report from her PET scan and her MRI data, they can no longer find the tumor, or tumors; she had like four of them. And all she was doing was calorie restriction and about 10 capsules of oxaloacetate.

There’s some real promise here, but it’s very early on. We don’t have the clinical trial data that supports this in a statistically significant manner, we just have individual cases. Although those individual cases are stunning, it would not be prudent to rely upon those cases.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Well, have you got any plans to have any clinical trials? Was that something that might be occurring soon in that area?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, well we’re actually in clinical trial for a variety of conditions. One is mitochondrial dysfunction. There are certain people that are born with genetic defects that affect the mitochondria.

We have one infant that’s been on oxaloacetate now for nine months that is showing normal development, whereas normally with this type of defect we would expect the infant to have passed away six months ago. So that’s pretty interesting.

We’re also in clinical trial for Parkinson’s disease because anecdotally we’ve seen some interesting cases where the oxaloacetate has reduced the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. And lastly, we’re in clinical trial for Alzheimer’s disease, so we’ll see how those all play out.

We’re getting ready to start some clinical trial work in pediatric brain cancer, because if we can get away from doing chemotherapy, it’s just a whole better quality of life.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It sounds like one of the main mechanisms. So if you’re looking at Alzheimer’s disease, they also use ketogenic diets, and so it’s obvious that the glutamate is helping, but do you think it’s also the aspect of improving blood sugar regulation is potentially helping in all these diseases as well? Is that one of the factors?

[Alan Cash]: It certainly could be a factor. We just published a paper in human molecular genetics that showed that oxaloacetate increased the amount of glucose that the cells could uptake in the brain, it increased the number of mitochondria in the brain. So we not only built more power plants, but we’re now having a way to fuel those power plants.

The interesting thing is that oxaloacetate is also a ketone. So you don’t necessarily need glucose to fire off all those neurons in the brain, you can actually use oxaloacetate as a power source. So, the other things we’ve seen with oxaloacetate in the brain in animal models is a reduction in inflammation, and probably most exciting is we’ve seen a doubling of the number of new neurons that are produced.

Ten years ago we used to think that the number of brain cells you have is static, that those brain cells that you lost in college are forever gone by imbibing in too much alcohol, but now what we’re seeing is that there’s an area of the brain called the hippocampus which continues to produce new neurons. And as we age, this function decreases. So our ability to repair our brains decreases.

Well oxaloacetate in animal models doubled that rate of production, and not only did it double the rate of new neurons, but the length of the connections between the neurons was also doubled. So, if you think about, well if a neuron can connect to a neuron that’s further away you get more interesting connections, more interesting abilities to have different variables.

It makes your brain more plastic, is what we say. And oxaloacetate has been able to show both that increase in neurons and the length of the neurons. So it’s pretty exciting work.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so brain injuries – you were talking about brain injuries before – I guess a lot of us think about brain injuries as a big thing, like maybe a car crash or something, you have a big serious brain injury. But now they are also looking at athletes, for instance in football where they’ve been heading the ball and areas like that, and they’re seeing there’s a lot of damage.

So could this potentially be a tool for sports? If you’re playing in football, would it make sense to be taking this stuff whenever you’re going to a match, or something like that, to reduce the kind of damage you’re getting each time you’re heading the ball, and so on?

[Alan Cash]: I think so. I mean, my daughters play volleyball at a very high level – one’s at Pepperdine, and the other is going to be at Hofstra next year – and occasionally they get hit in the head with a volleyball. They’re middle blockers, they go up, and they just get slammed in the face. So I always have a bottle of oxaloacetate in their gym bag, and if they get hit in the head they’re told to take 10 capsules right away and to continue taking 10 capsules for the next week or so.

I don’t want to suggest that you should use oxaloacetate for any kind of disease. Mostly it’s a nutritional supplement, there is the medical food also that’s specific for brain cancer. And I just want to make that clarification that the work really hasn’t been done in clinical trial.

Now, over in Europe they are working on that. They’ve done a lot of animal studies, and the interesting thing they’ve found is that if they can get oxaloacetate into these animals that have been hit on the head with a hammer within two hours, it reduces the amount of brain damage they experience by 80 percent. They’re looking at a lot of things in Europe, and it’s very, very exciting work.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, it seems like this is a really interesting molecule, because it seems to be having an impact in a lot of different things. Of course, it’s all early stages of research, like you say, but it seems to have quite a lot of potential.

I saw another study where they had combined oxaloacetate with acetyl-l-carnitine and they were looking at that. Could you talk a little bit about that? I believe it was long-term potentiation it was impacting.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, long-term potentiation is a measure of how plastic your brain is, how well you can still learn. And when they go into the brain of animal models and give them a stroke, an artificial stroke, and then measure long term potentiation, the levels drop significantly.

When they use oxaloacetate or a combination of oxaloacetate and acetyl-l-carnitine, they saw 100 percent restoration of the brain’s ability to learn again, in very short order. And this could be very important for people with stroke, closed head injuries, that type of thing.

But again, this is early work, it’s been done in animals, it’s been very successful in animals. And both oxaloacetate and acetyl-l-carnitine have very low toxicity profiles, so the risks are low there, but we still need to do this in clinical trial and make sure that there are no unexpected results in humans.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Yeah, so ALCAR or acetyl-l-carnitine, a lot of people I know have been taking it for a very long time. So in terms of toxicity for oxaloacetate, as you said there was the trials where you had 1000mg per day. Has anything above that been tested? Because it sounds like with some people you’re actually giving 10,000 or more in specific cases.

So, in terms of toxicity, is there any evidence to say that it could be harmful in any way if someone overdoses, or potentially someone in a specific situation?

One thing I was just thinking about while you were talking was in terms of glutamate, you say it helps to deactivate glutamate. In some people who are normal and have normal levels of glutamate, could that impact them in any way in terms of their brain performance, memory, things like that?

[Alan Cash]: That was a multiple question, and let me address them one at a time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I’m sorry.

[Alan Cash]: As far as toxicity, in order to bring the supplement into the United States we had to prove to the FDA safety because this is considered a new dietary ingredient, even though it’s in just about every food we eat but not at the levels that we’re giving it to people at. So we had to prove safety, and we spent quite a bit of money and three years of my life proving safety to the FDA.

One of the things we had to do is feed animals as much oxaloacetate as we could stuff into them to see at what point in time 50 percent of the animals would die. And what we found out is we got up to about 5000mg per kilogram of body weight in animals, and we still couldn’t get any of them to die.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Did you get any negative reaction at all?

[Alan Cash]: We couldn’t find one. Now, what we are seeing in humans, especially in some of these people with brain cancer that are taking the equivalent of about 60 capsules a day, we do see an increase in burping.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s interesting. It’s kind of random.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, well it relaxes the upper sphincter muscle in the stomach, and we see an increase in burping in some of the people.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s interesting.

[Alan Cash]: But that’s about all we’ve seen so far. So, from a toxicity standpoint, this appears to be a very safe molecule.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well, that’s great. Do you remember the multi-part question, or shall I repeat it?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, the second part was what if you take a lot of this and you’re just a normal person, what would you expect to see? Some of the things we’ve seen are really interesting.

We have an R&D project where we’ve developed an oxaloacetate tablet that goes under your tongue. And so we deliver a lot more oxaloacetate to the bloodstream, which preferentially reacts with glutamate. And what we see with that tablet is an increase in the ability to [unclear 40:04] because if you can turn down glutamate levels a little bit in your brain, you don’t have some of that repetitive cycling of questions, you’re able to focus more, you’re able to pay attention better.

It’s kind of like, the way I can explain it, it’s like you’ve been meditating for a half an hour, so you have this incredible focus but it’s not jittery. Like if you have 10 cups of coffee you can also have more attention, but your whole body is shaky. This is more, you’re very relaxed, and you just have that increased ability to focus. It’s pretty cool.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It sounds like you’ve been testing it yourself.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah I test it always on myself, because if I’m ever going to give it to somebody else you’ve got to feel confident enough in it’s effects to try it on yourself first.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. You know, it would be nice to hear, how do you use oxaloacetate yourself? Do you have some kind of routine, or what do you do with it?

[Alan Cash]: Yes, I use it primarily for anti-aging, because I’m after that [00:41:11 – 00:41:14:17 audio error repeated “we see an increase in burping in some of the people.”] I take like three caps a day, which is a little bit more than our recommended one cap a day, but I get it for free, so what the heck, right.

I’ve also started working with this sublingual dose whenever I’m tired. Like if I have to drive somewhere and it’s late I take one and immediately I’m awake and my focus is there. Or if I’m in a conference and its 4 o’clock on the third day of the conference I find that it helps quite a bit. So that’s how I use it.

A lot of athletes are using this now because we’ve been able to measure a decrease in fatigue and an increase in endurance. We don’t see an increase in strength, just an increase in endurance. So a lot of endurance sport people take one to two capsules about 15 minutes before competition, with about 100 to 200 calories.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So it sounds very quick acting, in terms of you’ve take it in and within a very short period it’s going to have that impact. Are you talking about it feeding the mitochondria, basically?

I mean, you spoke earlier about it basically being like a ketone. Do you think that’s the mechanism there, or is it because it’s stimulating the mitochondria somehow?

[Alan Cash]: Well there’s been some work out of UCSD showing that oxaloacetate activates pyruvate decarboxylase and allows the citric acid cycle to process faster. So you get more ATP production, which would tie with the endurance effect.

We’ve been able to measure the endurance effect almost immediately, and we published that in the Journal of Sports Medicine. We saw about a 10 percent increase in endurance. And you think, you know, 10 percent is not all that much, but in a lot of athletic competitions 10 percent is huge.

So that’s the short term effect, and that actually only lasts about two hours. And then if you want it again, you have to reapply.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So a marathon runner would be dosing every couple of hours?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, about every two hours.

The second effect though is longer term. We’ve seen that oxaloacetate supplementation increases the number of mitochondria, or the mitochondrial density in the cell. So it produces more of the power plants so that when you feed it more glucose, you can turn it into fuel faster.

But that takes typically, you know, anywhere from two to six weeks to see the effect on that. And you have to take it daily. What we’re doing is we’re increasing that NAD to NADH ratio, which then activates AMPK, and chronic AMPK activation has been shown to start the process of mitochondrial biogenesis, or producing more mitochondria.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Is there any reason we want that activated? Anything you know of like in the research, where it says like chronic activation of AMPK could lead to any downsides?

I have another question, just to kind of give you a bit of context to that. Is it worth cycling oxaloacetate? So having a month on, or a couple of months on, a couple of months off, or anything like that?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, a lot of supplements that deal with stressing your cells in order to get an effect they work better if you cycle them. For instance, echinacea. Echinacea works because it’s an irritant. So you turn on your stress response and get a response, but if you take it all the time, your body gets used to it.

Oxaloacetate doesn’t work as a stresser, it works to turn on genes and turn on the development of more mitochondria. So no you want to take it all the time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, and so we were discussing earlier, I was just asking you about potentially doing a lot of experiments with oxaloacetate, and you were saying that for most of the effects it’s really this aggregated, this cumulative effect.

We want to be using it for between two and six weeks before we see the effects. And then, if we stop it’s probably going to take that amount of time before those effects disappear. But they will disappear, so it’s something that you really kind of have to take on an on-going basis.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, yeah. Because it’s, well there are two effects. One is a pharmacological effect, like for instance the reduction of glutamate in the brain. That happens almost immediately, so some people when they take this they get that feeling of peace because they’re just reducing their excitatory chemical in their brain.

But the other effect is a genomic effect, and while your genes start producing these proteins right away it takes a while for the proteins to be enough in number that we see measurable effects. We can see those effects in typically four to six weeks.

For instance, blood glucose levels would be one that we’ve been able to trace that down to activating AMPK, which is the same thing that the diabetic drug Metformin does but through a different pathway, and the up-regulation of a gene called FOXO3A, which deals with glucose stability. But that takes time, it takes usually four to six weeks.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, for the people at home, if they were going to design their own little experiment, it would be basically measuring blood glucose stability, is that the main, is it the variant which is reduced, or is it actually lowered in general?

[Alan Cash]: One experiment that they could try is start off with a baseline. Go to the drugstore, get a glucose meter and some little paper strips, and take your fasting glucose levels for maybe a couple of weeks. You see the variability, because even in fasting glucose levels, you’re going to see the levels bounce all over the place.

And then start oxaloacetate supplementation, one or two capsules a day for a month, and take your daily glucose levels. You won’t see much change for about three weeks, and then what we typically see is a slight reduction – in non-diabetics – in fasting glucose levels.

And more importantly, a reduction in the swing. So you don’t see as high a high, and as low a low. And that reduction is typically on the order of 50 to 60 percent, so you have better glucose regulation. And in normal people, that’s not a bad thing.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Just if we’re talking in terms of performance, just throughout the day I think people’s performance goes up and down. Some of the reasons people try new diets such as Paleo and Ketogenic and so on is to try and even out their blood sugar a bit more so they don’t have these typical dips people get after lunch when they need another shot of caffeine to get through the afternoon.

So I’m sure probably you can see how that could impact their performance in that way. That would be interesting.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah. Absolutely.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So how would you recommend someone takes oxaloacetate? Would it just be 100mg one capsule? Would it be in the morning, once daily?

What would be the recommended way to try this out, for someone who is just normal and healthy, and they’re just more interested in the long term benefits, and so on.

[Alan Cash]: For the long term benefits, we looked at the minimum amount that you could take – I believe in small measures for big effects – the minimum amount over time, and we know that through the clinical trial that was done. We know that 100mg was effective in reducing fasting glucose levels in diabetics. We’re turning on those genes that we want to turn on.

So, one capsule a day. It doesn’t matter if you take it in the morning or the evening, what does matter is that you take it every day, because we’re trying to increase that NAD to NADH ratio and keep it pretty steady, so that we continuously activate AMPK. And that continual activation is what turns on the genes and gives us the gene expression that we want to see to see extended lifespans.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great, thank you. Are there any situations where you would recommended people – because you’re taking 300mg yourself, and obviously you don’t have the costs that other people would have – but are there other situations where you would think it would be interesting for people to take a slightly larger dose?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, but I really can’t recommend that, as I’m not a physician, I’m a physicist.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, right. We’re getting outside of the nutritional realm again.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, and that [can] be a dangerous thing for us to do.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely.

[Alan Cash]: Definitely our CRONaxal medical food for [treating] cancer, they would take a lot more oxaloacetate.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great. If someone wanted to learn more about the topic of caloric restriction and oxaloacetate, where would you say, are there any books or presentations or is there any other resources people could look up that would help them to learn more about this?

[Alan Cash]: Absolutely. There’s quite a bit in PubMed, so they could go to www.pubmed.com, or .gov, and just type in ‘oxaloacetate’ and ‘calorie restriction’. We’ve got some papers in there that we’ve published.

And they can also look at oxaloacetate and other things like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, cancer, you know, if they’re interested in that, and see what animal data there is out there right now. There’s not a lot of human clinical work done yet.

We’re in the middle of some of that ourselves. They can also email me. My email address is [email protected]. I typically get back to people in a couple of days with questions.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, and I can attest to that, because we’ve been in contact before and I know you make yourself very much available, and that’s really appreciated.

Are there other ways that people could connect with you? I don’t know if you are on Twitter. You have a website, of course, which is benagene.com?

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, we have a website benagene.com. There’s not a lot of information on that because the FDA discourages that. For instance, we can’t legally put any animal data on our site, even though I consider humans animals. I think it’s relevant, but the FDA does not.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, right. Of course. So, is there anyone besides yourself that you’d recommend to learn about this topic? I don’t know, calorie restriction, longevity. Is there any interesting stuff you’ve read over the years, or have you referred people’s work?

[Alan Cash]: There’s tremendous amounts of data on calorie restriction. And there’s a society, the Calorie Restriction Society, where these people have been restricting their own calories for years, seeing tremendous results, especially in reducing atherosclerosis. In human clinical trial we’ve seen a major drop in atherosclerosis and blood pressure.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Do you know if that’s reflected by the CRP? The C-reactive Protein biomarker? Because you spoke about inflammation earlier, I wasn’t sure if that was that marker or another one.

[Alan Cash]: I’ve seen a decrease in inflammation in our studies really through the M4 pathway. I don’t know if C-reactive protein levels are down. We did have a case where due to a genetic dysfunction an 11 year old girl, she was in critical care, her CRP levels were up around 20,000.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, yeah. She was…

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s insane.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah. Yeah. She was eating herself alive, essentially. And she was in critical care. They tried just about everything. And this was work done out of University of California San Diego Mitochondria Dysfunction Department. They’re doing some breakthrough work there.

They ended up giving her some oxaloacetate and in two days her CRP levels dropped to zero, and she was released from the hospital and went home. Once again, that’s a case of one person and specific genetic anomaly.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, yeah. Interesting. That’s pretty impressive.

In terms of your own personal approach to data and body data – because we’re always talking about data on this show in terms of our biologies and so on – do you track any metrics or biomarkers for your own body on a routine basis?

[Alan Cash]: Glucose levels. And for a guy, I’m 57 years old, my blood glucose levels are typically in the low 80s, which is pretty good. That’s about the only thing I track regularly. I mean I track my weight, which is very stable. I don’t count the number of hours I exercise or anything like that. I should.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I guess. Have you tracked your blood sugar over time? Before you started taking oxaloacetate, or is it since, so you probably wouldn’t see the effects? I’m just wondering if it would be a cumulative effect from you having taking it, I assume, for years now.

[Alan Cash]: I have been taking it since about 2007, which is when we introduced it into the Canadian market. Basically it just dropped. Initially I was up in the upper 80s to low 90s, and over time I’m just pretty much consistently in the low 80s now.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you have seen some kind of steady decline, or did it decline when the genes turned on and then it stayed there?

[Alan Cash]: It pretty much declined when the genes turned on and stayed there, yeah.

Now there’s ways to lower it even further if I went to a ketogenic diet. I know some people who have been doing this, like Dominic D’Agostino. I think his blood glucose levels are down in the 40s.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah. But he does a very strict ketogenic diet, and he’s feeding his cells with ketones instead of glucose.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so I was interested – just before we started the interview – also in just cancer prevention, so we had Thomas Seyfried on here and he recommended a five day water fast twice a year.

So it would be interesting to combine that with the oxaloacetate. It might have a potentially beneficial upside, you know, combining those two rather than doing them separately.

[Alan Cash]: Yeah, we’re seeing that in patients now. Hopefully we’ll be able to get some funding for some clinical trials to combine calorie restriction with oxaloacetate in some of these patients. To take the science from our animal data, which is very promising, but it’s not human data. And so hopefully we can continue our research and help some people here.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. I’m guessing it takes quite a while to get these clinical trials going. Would you expect this to be done over the next 10 years? Is there anything that could help you with that, in terms of getting funders, or what could help to push that along faster?

[Alan Cash]: We’ve taken the unusual step in brain cancer of making oxaloacetate available for a disease through the Orphan Drug Act in the US. So this allows for various medical conditions that have scientific basis to be used for a specific disease. In this case, we’re using it for brain cancer, which is an orphan disease.

So that’s helping get the word out, get some anecdotal cases, which I’ve discussed with you a little bit, and increase the interest in getting a clinical trial out there. We’ll see how that all evolves.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great. Thank you. Well, one last question Alan. What would be your number one recommendation to someone trying to use data, in some way, to make better decisions about their health and performance, or their longevity?

[Alan Cash]: I think that’s a great place to start. You know the benefits of calorie restriction, and so just counting calories and reducing calories where you can would be one strategy of using data to improve your health. If you keep track of that information.

Keeping track of blood glucose levels, because having lower glucose levels rather than higher glucose levels is going to positively affect your health. The amount of time you exercise.

One of the ways we’ve seen to increase the NAD to NADH ratio is chronic exercise. So calorie restriction is one way, chronic exercise is another way. A drug such as Metformin can increase your NAD to NADH ratio, or activating AMPK anyway.

And oxaloacetate as a nutritional supplement over the long term. So there are quite a few ways that you can use data and monitor your data to positively affect your health.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Alan, thank you so much for your time today. It’s been really amazing having you on the show with all of these interesting stories about these case studies about the work that you’ve been doing.

[Alan Cash]: Yes, and just as, again, as a disclaimer, we don’t want to recommend this nutritional supplement, which we manufacture, called Benagene, which you can get at www.benagene.com, for any disease.

Not to diagnose, treat, prevent, or cure any disease. It’s primarily, we developed this to keep healthy people healthy.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. And I take it myself too, so I’m kind of following in your footsteps there.

Well Alan thanks again for your time today, and I look forward to talking to you again soon.

[Alan Cash]: Alright, thank you very much.