In this episode we talk about improving your focus and meditation practice with the Muse Calm app. There are many benefits to meditation. Some find that it helps increase their calm. Other benefits include reducing stress, and changing the structure of the brain.

In spite of these benefits, many find it hard to either start or continue meditating. People wonder if they are doing it right, if they are making progress, or if they are getting results.

Muse is a meditation tech device that tracks your brain waves. Using the Muse Calm app, you get feedback on how focused your mind is. Users can see if they are getting the results they want. It also helps you refine your technique in the moment. This feedback and reward system makes it easier to practice long-term.

– Ariel Garten

Today’s guest is Ariel Garten. She is the CEO and co-founder of InteraXon, the people behind Muse. She has an unusual background as a neuroscientist, a psychotherapist, and a fashion designer. Called the “Brain Guru,” she’s known for integrating art and neuroscience.

Her research at Toronto’s Krembil Neuroscience Centre focused on regenerating the brain’s hippocampal tissue. She’s lectured about neuroscience and meditation at many events, including TED. Recently, Ariel was selected as one of the nation’s top entrepreneurial women by Ernst & Young.

The episode highlights, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

What You’ll Learn

- Ariel help found InteraXon to allow consumers to see into their minds (11:10).

- The Muse device is a consumer EEG to track brain waves and comes with Muse Calm, a mediation app (12:23).

- There are numerous other applications being developed for the Muse device, including for anxiety and ADHD (14:00).

- Doctors can incorporate Muse into their practice to help patients (17:18).

- The Muse device is easy to use, but electricity and movement can cofound the readings (20:20).

- The Muse Calm app was specifically developed as a focused attention training tool (22:07).

- By tracking four types of brain waves associated with different activities, the Muse device can give feedback on your focus (24:41).

- Brain wave activity depends on the person and the time of day, so Muse has you calibrate your baseline every session (26:55).

- Focused breathing is essential to developing a better meditation and mindfulness practice (28:35).

- Muse Calm can benefit both experienced and new meditators (30:25).

- Long-term data from Muse users show that people get better at meditating, and that the device helps with a variety of issues (33:07).

- Self-awareness lets you know yourself in a more meaningful way (34:54).

- The skills learned through using Muse Calm can benefit you in other areas besides meditation (37:46).

- Caffeine can either increase or decrease your ability to focus (39:10).

- Athletes use Muse Calm to calm their anxiety and improve their performance (40:27).

- Ariel personally tracks the time she spends doing certain activities, blood oxygen levels, and heart rate (44:44).

- Her biggest recommendation on using body data is to focus on your goals and choose data metrics that will let you reach those goals (46:15).

Thank Ariel Garten on Twitter for this interview.

Click Here to let her know you enjoyed the show!

Ariel Garten and InteraXon

- Ariel Garten’s Wikipedia page: Information about today’s guest.

- Muse: Find out more about the device and the InteraXon team behind Muse.

- Know Thyself with a Brain Scanner: Ariel’s TED talk on how understanding brain waves can let you know yourself better.

- Ariel’s Twitter account

- The Muse team’s Twitter account

Tools & Tactics

Tech

- Muse Device and Muse Calm: The Muse solution combines the Muse brain sensing headband – a consumer EEG (electroencephalography) device – with the Muse Calm app. The app provides direct feedback on your state of mind as you use either its guided meditation exercises or practice your own mindfulness or other form of meditation. The app is intended to reduce stress, increase focus, sharpen concentration, and relieve anxiety. Muse Calm works best on iPhone 4S or later, IOS 8 or higher, and Android OS 4.0.4 or higher. The app does not work on desktop or laptop computers.

Walkthrough How-to and Tips on Optimizing the Muse Calm Score

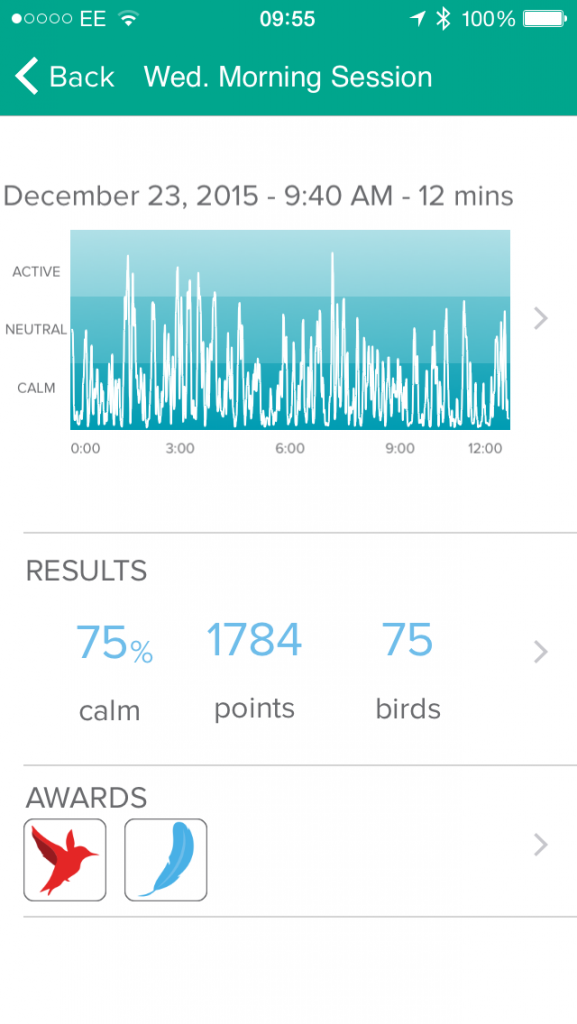

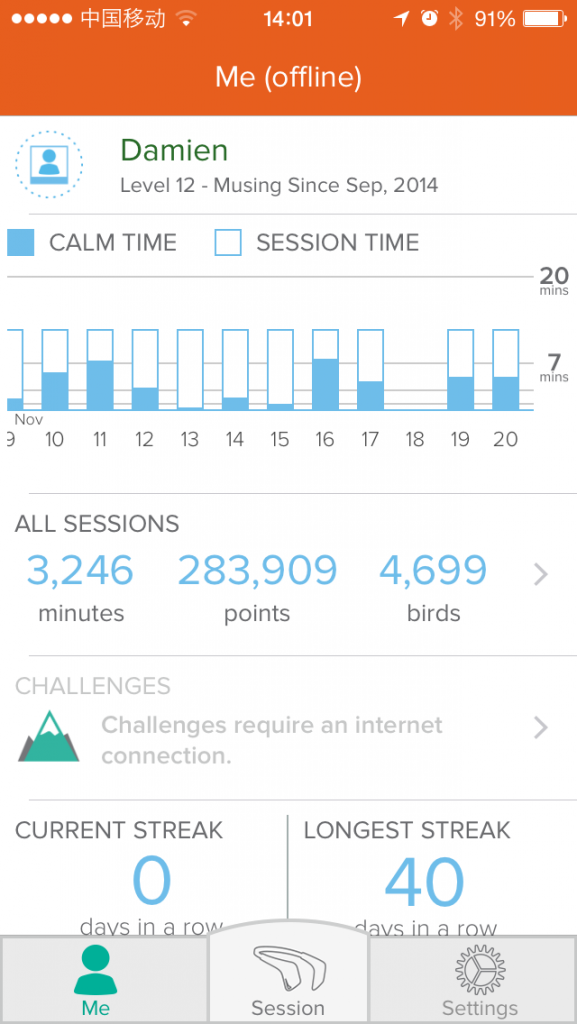

Screenshots from Damien’s Muse Calm App Results

Supplementation

- Nootropics: Sometimes called “smart drugs” or “cognitive enhancers,” nootropics are drugs or supplements that enhance mental function. The most commonly known are stimulants, including caffeine.

Exercise

- Mindfulness Meditation: Mindfulness meditation is the practice of sitting meditation. The ultimate goal is to be unconditionally present in the moment. Research has shown that mindfulness-based meditation can help alleviate anxiety, pain, depression, anger, and promote well-being.

Tracking

Biomarkers

- Brain Waves: The brain produces a range of waves, each associated with different activities and levels of consciousness. Delta waves (0.1 – 4 Hertz) are seen when you are asleep, and theta waves (4 – 7 Hertz) are seen during dreaming or relaxed states. Alpha waves (7 – 14 Hz) can be seen during both relaxed and focused states, while Beta waves (15 – 30 Hertz) are seen during focused cognitive processing. Gamma waves (30 + Hertz) are associated with consciousness and potentially cognitive process.

- Blood Oxygen Levels: Blood oxygen is the amount of oxygenated hemoglobin in the blood compared to non-oxygenated hemoglobin. Blood oxygenation is important for physical performance and cognitive function. The normal range of blood oxygen levels at sea level for a healthy adult is 96 – 99%; anything less than 94% indicates that you may have a health condition.

- Heart Rate: Heart rate is measured in beats per minute. For most adults, normal resting heart rate is between 60 and 100 beats per minute. Better cardiovascular health is associated with a lower heart rate.

Lab Tests, Devices and Apps

EEG Devices

- Biosemi EEG: An EEG system designed to be used specifically in research settings.

- Brain Vision actiCHamp: A research amplifier that combines components for all electrophysiological research into one componenet.

Personal Fitness Trackers

- Pulse Oximeter: Used to assess levels of blood O2. An example of one of these devices can be found here.

- Up by Jawbone: This product tracks sleep, activity, and nutritional information.

- Misfit Shine: A waterproof activity logger, the Misfit Shine can be used to track various activities.

- FitBit: The company makes a variety of different personal activity loggers, including the Fitbit Charge.

Other People, Books & Resources

People

- Sam Harris: Sam Harris is a neuroscientist and an author on meditation and spirituality.

- Brian Orser: A Canadian skating champion and Olympic silver medalist, Brian Orser currently coaches competitive skaters.

- Javier Fernandez: Winner of the 2015 World Championships and the 3-time European Champion. Javier represented Spain in the 2010 and 2014 Winter Olympics

- Nam Nguyen: A Canadian figure skater, Nam was the 2014 World Junior champion, 2014 Skate America bronze medalist, and 2015 Canadian national champion.

- Jon Kabat-Zinn: Dr. Kabat-Zinn is the founding Executive Director of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He is also the founding director of the Stress Reduction Clinic. He teaches mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), is the author of numerous scientific papers and books.

- Daniel Goleman: An internationally known psychologist, Daniel Goleman writes about the brain and brain science, including for the New York Times.

- Dr. B Alan Wallace: Dr. Wallace writes and lectures on incorporating Buddhist contemplative practices with Western science to advance the study of the mind.

- Dan Harris : Journalist and author on the topic of his personal journey to understand the benefits of meditation.

Organizations

- Mayo Clinic: a nonprofit medical practice and medical research group based in Rochester, Minnesota. The Mayo Clinic is currently using Muse Calm to reduce stress in cancer patients.

- Baycrest Health Sciences: A global leader in geriatric residential living, healthcare, research, innovation and education, with a special focus on brain health and aging. Baycrest is currently doing a study on the effect of Muse Calm on blood pressure

Books

- Waking Up: Recommended by Damien, Sam Harris’ book talks about spirituality without religion.

- 10% Happier: A book about Dan Harris’ (described by our guest as a “self-absorbed journalist”) as he changes through meditation.

- Search Inside Yourself: Chade-Meng Tan, one of Google’s earliest engineers, teaches readers the same skills in mindfulness and emotional intelligence that he teaches Google employees.

- Emotional Intelligence: Daniel Goleman’s book about the importance of emotional intelligence in success.

Full Interview Transcript

(11:07)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Ariel, thank you so much for joining us.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: My pleasure, happy to be here.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Could you share a little bit about how you became part of InteraXon and you got to do what you’re doing today?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Sure. I’m so lucky to be doing what I do today, I have to tell you, I’m really, really thrilled. I founded InteraXon with my co-founders Chris and Trevor about six years ago, it’s actually our sixth birthday tomorrow. Prior to that I was working in a research lab where we used primitive brain computer interface software to allow people to create comfort with their own mind, so they’re actually creating musical experiences.

From there we went on to allow people to control physical stuff with their mind in a very basic way, and this entire time we recognized that we had this amazing technology that allows you to literally peer inside your mind, connect your mind to a device and then do something. So we created InteraXon to really find out what that “something” is that we could do with it and bring a product to market that was ultimately going to help people by.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: So, is the innovation with InteraXon, as I understand, it’s because you’re enabling consumers to get in touch with this, whereas a lot of the devices beforehand have been clinical – they’re not exactly very accessible. Is what you’re doing based on trying to make this more widely available, or are there some other specific innovations involved that you’ve brought?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: There are a lot of innovations involved and certainly being more widely available is one of them. The Muse is – for people who don’t know about Muse – a clinical-grade EEG, its seven centers that deliver four channels of data, two on the forehead and two behind the ears. It tracks your brain activity in real time and sends it to your smartphone or tablet.

From there, the application that Muse comes with is basically a meditation tool – focused attention training tool – that teaches you to improve your attention, decrease your stress and learn to self-monitor and self-regulate.

In terms of the innovation, it uses clinical-grade EEG. It’s a dry system, so it’s very sleek, very fun, very easy to wear, and it’s mobile. Our innovation’s around getting EEG to fit easily on any head, getting something that really is just a part of your daily life and it looks like any other wearable device, like a Jawbone UP or a Fitbit.

It’s a little device that you wear as part of your daily life or at home. I sometimes wear mine to parties and people think that it’s actually part of my outfit!

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: So are you actually using it to track your brain waves while you’re at a party or is it more for decoration?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: I have to admit that I sometimes do that, yes, because I am a neuro-nerd.

(13:34)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Well, I’d be interested if you’ve learnt anything about yourself, because I’ve been using it, of course, just for the meditation, with your app Calm since September now. So I’ve been using it specifically for that.

This is basically a consumer EEG device that you’ve made available to people. I understand that you’re going to be able to add other different applications on top of it. Today we have the meditation app called Calm, but there’s potential to add different apps also?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yeah, we actually have an ecosystem of hundreds of developers. The SDK is open so anybody can build on top of the Muse platform.

We have people doing things like drowsiness detection, building simple game-based interactions, using it for more complex healthcare needs that are also game-based. There’s a group out of Europe that is doing beautiful applications for kids with anxiety, there’s two groups that are creating lovely applications for kids with ADHD and through gaming they actually improve their ADD/ADHD symptoms. The first one has gone through the first trial.

Then we have over probably 50 different research institutions that we’re working with that are using Muse. Mayo Clinic for example, are just beginning to study the Muse to decrease stress during cancer care; NYE has been using it to look at learning and memory, so true variation across the board – some of them are just fun gaming things, some of them are really serious medical applications.

Then, of course, there is our application that we’ve built called Calm, that comes shipped with the device, and that is a beautiful experience that helps you to understand and improve your own mind.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: That’s excellent, I didn’t actually realize that you had as many projects out there. I guess a lot of these we don’t hear about because they’re done more in very specific niche areas, so unless you’re actually looking into the clinical applications…Are these with doctors or are these in universities primarily that it’s being used at the moment? Are there any doctors taking interest?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: We have quite a number of doctors that actually use Muse as a part of their practice. We have a pediatrician who has a Muse room and when kids come in, she can send them to the Muse room to do focused attention training. We have other doctors that recommend the Muse for issues like sleep anxiety and depression. In North America, if you have a naturopath in your clinic, the naturopath can actually sell Muse at the front desk.

Then we have health care institutions that we’re working with to do broad scale studies. Baycrest, it’s a geriatric care facility in Canada, they’re doing a study on Muse’s effect of blood pressure and affect; Mayo, as I said, is doing their study on stress in cancer care patients; I’m trying to think what other ones I’m allowed to mention, but there’s quite a number of them going on.

(16:13)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Yeah that’s a lot. I want to talk more about the meditation one now, because that’s the one that’s more widely available to people right now.

For some of these applications, like some of these things other people would be interested in – just like increasing focus and attention, things like that – will these be more widely available or are they going to stay in these niche applications, like with physicians working with them? I guess you’ve got a more private program working with those or is there somewhere someone could go to download these and use them with the Muse headset?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: These are all in very early prototypes that people are building themselves. So from a year forward, you’re going to start to see these things enter into the Muse ecosystem. Some of these studies that are running, like the Mayo Clinic study for example, they’re fusing Muse Calm, using the existing software that comes with Muse, and they’re applying it to these various health care settings.

When a doctor recommends Muse, he’s recommending the existing application, Muse Calm, to help his patients with sleep or anxiety or depression.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: So they’re using Muse Calm and then seeing what the impact is on insomnia and some of these outcomes. Is it mindfulness techniques they’re using?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yeah, Muse basically teaches you how to meditate. The doctor, if somebody comes in with heart disease, one of the main prescriptions for them is actually change your diet and learn how to meditate so you can manage your own mind and decrease your stress.

Patients will then say, “Okay, how do I do that?” and they walk away and absolutely nothing happens. So now they can come into a doctor’s office and the doctor will say, “Well you should meditate” and frequently they’re saying, “you should meditate and you should use this device. This device is going to teach you how to calm yourself, improve your focus, manage your urges and your cravings, manage the stress in your life, and I will know that you’ve used it because you can come back, you can show me your data, you can show me how you’re improving, we can talk about how this works for you” and it becomes a really actionable tool.

(18:06)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right. The reason I approach this is as soon as it came out, it was because meditation is one of those things that everyone would like to do and everyone would like to do it properly. I’ve been doing it for many years, and honestly, I found it difficult to know how effectively I’m meditating.

I think this is something that a lot of people struggle with when they’re trying to meditate, so it was really, really an interesting device for that reason for me to get hold of.

I want to talk to you a little bit about, first of all, the EEG, you said it’s clinical EEG; so has it gone through specific tests to show that it’s exactly the same output as the bigger contraptions that people are used to when they go into hospital for example, or are there slight differences? What does it mean that it’s clinical EEG?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: We’ve had third parties, hospitals, go through the processes, comparing Muse to Biosemi and to Brain Vision actiCHamp – these are 30 to 50,000 dollar systems that are clinically used – and their analysis came back that it is not statistically different from a clinical-grade EEG.

To be fair, there are only four channels. In those four channels you’re getting the same readings as you would get from a clinical EEG. We can’t see the rest of your head, where you may in a clinical EEG also have sensors on the top of your head and the back of your head.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Typically how many channels are there on a hospital-based machine?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: It depends. There can be anywhere from 19 channels, 32 is common, or all the way up to 128 or 200 and more depending on the application.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right. So is it sensitivity? What would be the difference between having more or less channels?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: It really depends on where on the head you need to measure and what you’re trying to do. More of anything is typically better, but we found with four channels you can actually get really great data. We’re able to look at the difference between left to right, back to front, we can do some very basic mapping on focal localization – where is the signal coming from in the head – once you have four channels.

For the applications that we’ve been building, this is the perfect channels for the perfect head for the outcomes, and no goopy gel and no wires and no doctor on the other side of the room looking at your data.

(20:20)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right, exactly. I think that’s the important thing to emphasize here, that it’s a lot more convenient than the standard EEG systems – where you have to put gel on your head and it’s kind of messy; this thing, you can just put it on and take it off as you want.

One interesting thing that I noticed: I was wearing headphones – I don’t know if you know this too; I imagine you do – so obviously with a wire, and I found that sometimes I wouldn’t be able to get a signal when I was wearing the headphones and it was irritating me. Then I realized it was because it must have been an electrical signal coming through the wire in the headphones. I’ve got these other air ones now and I don’t get that, so I don’t know if that’s something you’ve seen before?

I just wondered, what kind of confounders could people come across, or things that they should avoid? I think another one is that you shouldn’t be moving, right? You have to be still.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes. EEG is very sensitive. EMG – muscle activity – is much, much louder than EEG, so in order to use an EEG, you have to remain quite still and relax the muscles in your face and neck. That’s the main confounder.

Then if you’re in an insanely electrical environment, you may find that your signal’s having some issues, but overall that should be fine because the electrical lines would be affecting both the ground and the reading channel, so ultimately that should cancel itself out.

But in most environments, it’s pretty good. You can even do it on airplanes. Sometimes when it starts to get really turbulent, then your signal has an issue, but overall, you can use it on the plane.

(21:47)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Great. So it sounds like its best suited for meditation, where you’re really not doing anything. If you wanted to increase your focus, like say attention on a task, are there applications that are potentially coming out later that we’ll be able to use to do that?

If you’re working on your computer, you’re moving your head a little bit, from side-to-side, probably not thinking about it much.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yeah, actually the best thing to improve your focus on a task is to do the existing application with Calm. It is literally a focused attention training tool; that’s what it’s been built for.

When you Muse, you focus your attention on a single object, and as soon as your mind wanders, you get a notification and then it’s your job to bring your attention back to the single object. The more you’re able to maintain that state of focused attention, the more you’re rewarded by points and birds and all sorts of fun stuff.

I joined a study that we had internally really early on, and after my first two days of Musing, I was doing a long form essay. Typically, these things take me three or four hours to do because I’m distracted, I think about something else, I obsessively check my emails – and this time I started typing and kept typing and I had a slight urge to do something else, now I’m coming back to what I’m doing. It was just phenomenal for my focus.

(22:58)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Yeah, there’s a lot of research on the benefits of mindfulness meditation for increasing these things.

I’m wondering, when you wear you device in other scenarios, have you learnt anything interesting from it? You said you would sometimes wear it to parties or anything like that; have you learnt any insights about yourself or anything you’ve learnt from it?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: There’s a couple of really funny examples. I’ve noticed the correlation of my brain activity over the day and with weather. Prior to it raining and when there are changes in pressure systems, I see big decreases in my data activity, decreases in my down activity. I’m like a human barometer in some ways, it’s quite cool.

Another pretty fun story: I was actually on stage and projecting my brain waves live during a presentation that was in Paris. The presentation was in English and then it came to Q & A. Somebody asked me a question in English; my focus spiked a little, I answered, it was not a big deal. I then tried to answer another question in French – being Canadian I marginally speak French and I thought I could show off to the audience – and the audience started to rustle and giggle and I didn’t realize why.

It wasn’t my French, it was my brain activity: my level of data activity had just shot straight through the roof as I was trying to figure out how to answer in French. Then as I started to answer, you could see it come back down again as I’d gone through the processing.

The audience figured this out well before I did – it was behind me, I couldn’t even see it – and so then they started asking me questions in French, playing with my brain activity! Hacking my own brain on the stage, it was really cool.

(24:41)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Taking a little bit of a step back; you described a few different waves there, so the Muse is tracking four different types of waves? Could you give a bit of background for the people at home who aren’t used to these different types of waves and what the purposes of them are?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Sure. The Muse tracks full spectrum EEG activity, from about half a Hertz, which is as low as the EEG is ever going to go, up to EEG that we tend to talk about ending in around 50 or 60 Hertz. 60 Hertz or 50 Hertz when you’re up with activity from the electrical activity in the room, like your lights, etc.

Muscle activity tends to be from 40 Hertz up to hundreds and hundreds of Hertz. EEG is typically broken up into different bands. Delta activity is the lowest wave of activity – that happens predominantly during sleep. Theta activity is from about 3 to 7 Hertz – that happens when you are dreaming or highly relaxed, and also during sleep. Alpha activity is from 8 to 12 Hertz, and that is both a relaxed state and a focused state. Then beta is from 13 up to 35, that’s intense cognitive processing – so if you’re thinking about something, your brain is working.

Then from 35 up, and there’s debate up to how far that up goes – some people say it goes even up to 200 Hertz – we have gamma activity, and gamma is associated with consciousness and a bunch of other very fun things. Sometimes also seen in the meditation literature.

When you go through and you get an EEG, often it’s broken up into these bands. Somebody will say where you’re falling asleep, you know we’re seeing an increase in delta activity, or you’re processing, we can see a lot of beta activity right here, so me trying to speak French, it was very beta. And me relaxing is very alpha.

When we run our algorithms for Muse and we use Calm, what we’re looking for is a state of focused attention and we’re looking a little bit at this band-based activity, but we’re also doing machine learning on your brain activity, and so we’re not saying, “Okay, well, you are in beta activity so you must be focused”; we’re saying, “alright, let’s look closely at what your brain is doing and let’s build a model for your brain that we can then apply much more settled times of thinking and interactions around, rather than just ‘are you in beta? Are you in alpha?'”

(26:55) [DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right, that’s interesting because I wanted to ask you about how the algorithm worked, just for the people at home. When you first put this application on and you’re going to start a meditation session, it asks you to calibrate, so it asks you to think about some things – so you’re trying to generate beta, I guess, at that time, or the equivalent of beta, like basically, a lot of thinking activity – as a control, and then you try to compare that.

Is it because brains are very personal, is that why you have to take that approach?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, absolutely. You do a calibration, so we’re looking for the baseline that day. We’re not just looking at beta; we’re looking at all sorts of different things in your brain at that moment. Then we’re seeing how that compares with two sessions that you’ve done previously and to the session that you’re about to do.

We’re able to see a real snapshot of your brain at that moment in time, because not only does your brain differ from day-to-day, it also differs at different points of the day, it differs based on how much caffeine you’ve had, how much sleep you’ve had, the environment around you at that moment.

So we take all of that into account looking at your brain activity, and deciding how you’re going to respond to the algorithm experience.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Basically, it gives you a score – it gives you percentages of calm. Would that vary, would it be relative for each session? Is that what you’re saying – say it was a different time of day or something like that, it will say “for this time of day you’re basically doing well”?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes. Your calm score is relative to your calibration.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: The immediate calibration immediately before?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Exactly, you do calibration every session.

(28:35)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right. I guess the important thing there is like when you’re given the instructions to think about things, you have to do that properly, otherwise that won’t work as effectively?

Mindfulness-based meditation is a type of meditation that has the most research on it. I don’t know if you’ve compared it to mantra or some of the other types of meditations and if you specifically chose mindfulness because there was more research? Could you talk a little bit about why you made the decisions to design the application the way it is?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Sure. The application that you’re getting is specifically a focused attention training focus, focusing on your breath. This action of focusing on your breath tends to be a really first-line thing that you learn when you learn mindfulness and you learn to meditate.

Once you build your state of focused attention, you can then start to apply it to anything, and you can move your attention around your body and do a body scan for example, or you can move your attention around your environment and do open monitoring, or listen for your own thoughts and put your attention on your own thoughts.

With Muse you’re really doing a core exercise that teaches you this muscle of attention and builds it so that you can then go on through the range of experiences. The application offers a range of teachings that are available in mindfulness and meditation.

The application that we’ve built works very specifically with the focus on your breath, so it doesn’t work with the body scan, it doesn’t work with the mantra meditation, though we will have more exercises like body scans being added to new Calm.

(29:57)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Great, and you’ve just actually come out with an upgrade of the original app. The thing I noticed, it used to have difficulty levels, and I think they’ve disappeared now. Is that correct? Or are they still there and I just can’t find them?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, difficulty levels have disappeared, and I think we’ve replaced it with volume on the wind.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Oh really, that’s interesting. So are there some things you’ve learnt over the past six months that you integrated into the new app which were interesting?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Absolutely. There are two classes of people who love Muse: one is experienced meditators, and we would hear things from them like, “We don’t want the volume, we don’t want the real time feedback, we just want to see after the fact how we did.” So we now have a volume switch so you can turn off the different sounds, so less to be rewarded by a sound or it’s going to your score at the end.

The other class of people who love Muse are people who kind of know they should meditate but really have no idea about how once they’ve started and it’s really hard to stick to a practice. One of the things that we’ve really learned from that audience is about motivational architecture and what’s required to encourage them into the experiences of meditating with Muse and how you create an experience of motivating and sticking – you just want to come back and do it and you just want to do it every day, and before you notice, you’ve built yourself a meditation practice and that thing that you know you should do is a thing that you’re actually doing.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Yeah, so you’ve integrated a little bit of gaming in there. The birds are still there, as well as the win?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Okay, great. So you had these birds come along when you were being really good and you were being calm for a while and they start chirping, so I think that’s one of the things you’re saying you can turn off the volume on the birds – is that it?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Because some people were saying that was a distraction for them, the way they like to meditate; whereas other people need that feedback to know they’re doing good, as you say, for motivation.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Exactly, so the vast majority of people love birds, and I will get random texts out of nowhere like, “My grandfather just tried Muse. He got 87 birds,” which is a lot. And people just get very excited about birds. Then every now and again, I hear somebody say, “I hate those damn birds. I’m really, really calm and then they start going.”

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right. Because there is just that little temptation to start listening to the birds, which I guess is starting to interfere with the mindfulness. But in order to add neurofeedback, I guess you need…

[ARIEL GARTEN]: If we’re talking about the birds for a second, because that temptation to listen to the birds is actually part of the experience. Everybody who complained and said, “Those damn birds,” it’s kind of funny because those damn birds are actually part of what’s challenging you.

The goal of mindfulness and meditation, you will ultimately be triggered by something, you might be rewarded by it, and then you get really excited about this reward and then the reward leaves. You’re trying to move to a place of equanimity, where you are not pulled either towards the positive reaction or negative reaction towards something. So these birds are actually there to subtly reinforce these lessons of equanimity.

But if somebody’s not ready for them, you can turn off the volume.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right. As you get better and you get more birds, you’ll basically be more challenged?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, and more rewarded, which is also your challenge to not get excited by those rewards.

(33:07)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Yeah. I was wondering have you learnt things from using the app, because it’s been out for a while now and I guess you have a lot of data from people. I don’t know if there’s anything you can talk about that you’ve learnt in terms of how people learn and how long does it take to learn to get better at mindfulness-based meditation, or anything like that.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: One of the things that we’ve learned is that people get better. We can see people’s Calm scores and how they improve over time and track those improvements. It’s astonishing; people really stick with it and get better.

We’ve done some fun diagnostics, which is the Calm City. I will check back and send you an email and let you know which city it was. That was a fun little study that we did.

We’ve also learned of the different ways that this can make an impact in people’s lives. I’ve gotten tremendous emails from people. The first one I ever got was a girl who was 27 years old with ADHD. She’d stopped taking medication four years ago and she said within three or four days of using it her parents had noticed a difference. Then within three weeks of doing it, this to her was not a game changer; it was a life changer.

When you give people this small ability to learn that they can actually manage and direct their own mind, extraordinary things start to happen in their lives. If you go and look in our Amazon comments, there’s a woman’s husband with cancer and she was using this to manage the stress of his cancer. There’s another woman who had heart palpitations and was using Muse to manage her heart palpitations and she stopped having them and stopped taking her medication.

When I hear those things, I strictly say, “No, keep taking your medication. It’s not a medical device. It’s not indicated for this.” The things that people are discovering about themselves and how they can learn to manage themselves through non-medical easy to implement tools is pretty amazing.

(34:54)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: I know from your TED presentation that you’re a big believer in building self-awareness. Could you talk a little bit about that and what it means to you?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Self-awareness is about being able to know yourself in ways that are meaningful to you. There’s a whole lot of navel gazing that one can do that’s not necessarily useful, and quantified self tends to get very caught up in data. To me, the data is not the important thing, it’s our own human experience. I think data often takes us away from that human experience, which is why we wanted to create a tool that just was based on real time feedback so that you can learn about yourself in real-time in this way that’s really intuitive, really quite emotionally lovely.

As a psychotherapist, and with the [psychotherapist part starting to interact on –??], my job is to help people understand themselves. We have so many things that govern our reactions every day that we have no idea about.

A cliché example, that fight that you had with your boyfriend that comes in and causes you to snap at your boss or your co-worker or your child; you don’t know why is the thing that causes stress and grief and strife and undoes the lovely world that most people are trying to build for themselves. When you have the ability to know about your own internal state and your own internal motivators – these motivators that previously had been secret motivators, hiding deep in your subconscious and below the surface, and just guiding your actions without you even realizing it – when you have the ability to begin to dig in there and to decompose your actions into those subparts that truly are the motivations for your actions, you can live a much better, much happier, much more pleasant, calmer life.

You’re not creating drama and distress and perpetuating discomforts that are your own internal discomfort by putting them on somebody else in ways that you may not have previously realized.

(36:55)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Thank you for that because it’s something I feel is very important too, and obviously the Muse device can help to give you these kinds of insights. Do you recommend people do it at a specific time in the day?

One of the things I’ve noticed is that my morning sessions are always a lot calmer than my evening sessions, basically after I’ve been working and doing things like that. Is that very typical? Is that the kind of thing that you would expect?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Often people’s morning sessions are calmer than their evening sessions, yes. You can do Muse anytime, so the right time to Muse is anytime when it fits best into your day. Some people do it in the morning and set themselves up for the day; other people take it to work and will use it when they have a little break and they need to focus, or when they’ve had an issue and they just need to calm down; and then another set of people do it in the evening to shed the day, or right before bed to improve their sleep.

(37:46)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: You were talking about it earlier, if something upsets you in your life and maybe you’re not that aware of how much of an influence it’s having on you. Have you heard of case examples where people are using it just to get back in touch with themselves after something? It could be maybe they had a big dose of caffeine and they’re not sure how much of an effect that has on their ability to focus and relax and so on, or maybe it’s when they’re in contact with a certain boss which they find a bit disagreeable – have you heard of examples where people are using it just to touch base with themselves?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, and to be clear, Muse is not going to tell you that you’re sad, or Muse is not going to tell you that you don’t like your boss; all you’re getting is this feedback of focused or not focused.

But it’s that action of learning to quiet your mind and look inside yourself, and that action of knowing that you can actually observe your own thoughts and take the time and space internally to focus on your own thoughts, that leads to those insights.

And that leads to this state that in the past where your boss had said something really annoying and then you feel the anger rise, you don’t just immediately jump on him and respond the way that’s probably going to threaten your job; you’re able to take the time to then recognize what’s going on internally and respond appropriately.

But we have a bunch of quantified selfers who do fun things like track their neuro response to caffeine, etc.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Are there other thing, like caffeine, which you would say typically disturb it that people should be aware of? Because if they’re using this and they’re upset with their scores because they’re not getting what they should be, are there other things that they could be doing in their life that might be interfering?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Caffeine – we actually have a relatively personal interactional score. It’s not only the bad thing, and for some people, caffeine really helps you focus. For other people who are over-caffeinated, caffeine makes it very difficult to focus. So it’s not yes or no caffeine, it’s the dose that is actually making you productive.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: That would be interesting. Potentially your score in Muse might translate to productivity in some areas as well, so they could tell if caffeine was having a positive.

We all take caffeine and we think it helps, but I think it could help in some situations for some people, and for others it may not be helping – like making us more distracted. So that could be a correlation there.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, potentially. It’s something to think about. A fun experiment for somebody to run.

(40:11)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Great. Are there any others that you can think of offhand, which people could be aware of that might interfere or have an influence?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Anything that has really aroused you that day, so if your heart is beating and you’re anxious about something, it’s going to show up in your Calm score and that’s what Calm has been teaching you to calm back.

(40:27)[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: How about exercise? Would that have an impact?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: I haven’t run an experiment looking specifically at the effect of exercise on Muse. But, we have quite a number of athletes who use Muse, so we know a lot about the experience of Muse on exercise.

We’ve done programs where you Muse prior to your workout, and people report significantly better workouts – they’re able to push themselves further.

Then we have a good handful of Olympic athletes who’ve been using Muse. Most recently I was talking to you may not know him, he’s a Canadian skater – it’s really valid, and it’s exciting here. Brian Orser is a Canadian Olympic skating championship and he’s been training two amazing young skaters, Javier and Nam. They have been using Muse prior to the World Championships, which just happened a few weeks ago. Javier came in gold in the World Championships after Musing, which is amazing.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: It’s competitive advantage!

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, definitely a competitive advantage. And Nam is 15 or 16 years old and I went and I spoke to him after his World Championships. We sat down and he was telling me, I’ve no idea how he’s been using it, but he said that he Mused every day. Prior to Musing and prior to being introduced to me, he would be really distracted and nervous and felt all these incredible social pressures on him being so young and having to perform.

He’d be Musing all the time to get that down and to learn to manage his own anxiety. He’d Mused 15 minutes before every performance, and he Mused 15 minutes before his performance at the Worlds, where he came in fifth at the age of 15 or 16 in the World Men’s Skating Championship.

I heard this a week ago and I was overwhelmed, kind of beside myself.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: That’s amazing. There’s so much research on mindfulness proving these kinds of things. It’s great to hear examples where it’s actually happening in the real world.

For the people at home, I guess there are a few things that could be influencing that. First of all, neuromuscular control is basically driven by the brain, so even people lifting weights, they can do better. Or people using nootropics for example, as well – if you’re improving your brain, you’re going to have more control and you’re going to be basically stronger.

Then you’ve got all the coordination and these complex sports and everything like that, which obviously is a lot more brain driven as well. So, there’s definitely a very direct relationship there.

Thank you for those examples, it’s really interesting. If someone was looking to learn more about your topic, are there any books or presentations on the subject, like your TED talk for instance, or is there anything else related to the Muse and some of its applications we could look up?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: You can always go to our website, choosemuse.com. We’re going to go through a website rebuild pretty soon with more and more information and resources there for you.

Then of course there is the entire canon of mindfulness and meditation research. I’ve loved talks by folks like Jon Kabat-Zinn, he’s got a good-old [unclear 0:43:26] school pep talk that teaches you about learning about mindfulness and the impact it can have in your life.

If you’re looking for something really, really accessible, Dan Harris’ book “10% Happier” is really fun. It tracks a journalist, narcissistic, self-absorbed journalist who changed through mindfulness, so lots of really interesting stuff there.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Right, thank you for that. If people want to connect with you, are you on Twitter? What’s the best way to connect with you and follow what you’re up to?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: You can find me on Twitter, @ariel_garten. If you type in Ariel Garten you’ll find me. And Muse is on Twitter @choosemuse.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Okay, great. Is there anyone besides yourself you’d recommend in this area, basically like you’re saying, I guess those references you already gave out would fit that.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yeah, sure. Meng from Google wrote an amazing book, “Search Inside Yourself.” It’s sort of an engineer’s perspective on mindfulness. Alan Wallace is always a great one to look into. Daniel Goleman has a great book on focus that ties neuroscience and mindfulness and focus. I can keep going!

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: It definitely sounds like you’re passionate about this stuff. I’m also interested in just more general, like whether it’s with Muse and meditation or in more general, are there metrics or biomarkers you track for your own body on a routine basis, and things that you use to keep an eye on yourself and you take an interest in?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: For myself, as I said, I’m not into data-driven quantification in the same way because for me it’s about having an actual human experience and data is there to support it. Definitely I’m aware of the amount of exercise that I do, I don’t count my steps but I count the amount of time that I spend in activities like walking, dancing, ice skating, climbing, etc.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Is that through a device?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: I just have weekly goals for myself, and I just do it on a calendar basis.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Are there any lab tests or anything like blood markers that you look at from time to time? Or is that awkward for you?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Oxygen levels was one I was having fun with for a while. I began very interested in a relationship between oxygen and both cognitive and physical performance. I have a CO2, just a little blood oxygen reader that you clip onto your finger that connects to my iPhone. I’ve tracked my blood oxygen levels in really fun places, including up in planes, and it’s also interesting to then start to look at people of different ages in the same situation and track their blood oxygen levels and see how they’re doing relative to myself. And of course, I’ve got the ones like heart rate.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Yeah, I’ve played around with that a little bit as well. I didn’t really find a lot of change in myself; did you find some interesting things about that in different situations? I didn’t try on the plane one though, which would be the more extreme one, right?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Definitely with altitude the change becomes very, very clear. Then when I’m fatigued, I see a change in my blood oxygen levels.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: What would be your number one recommendation to someone trying to use data to make better decisions about their health, performance or longevity, whatever they’re interested in?

[ARIEL GARTEN]: I would say focus on your goals and choose data metrics that are going to directly lead you to those goals. If fitness is a goal, your step counting is definitely the easiest and simplest way to start. And for absolutely any individual who wants to motivate themselves to lose a little weight and get a little fitter, get a Fitbit, Jawbone UP, Misfit Shine, any of the above and just start to engage in the understanding of your activity and have an impact on your life and simply be active, beginning that correlation will be motivating you to improve.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Yeah, it sounds like you said the greatest benefit is accountability, like a motivation for a lot of these devices.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: Yes, for level one, yes. If you are an athlete in the 90th percentile, you’re well beyond motivation and you’re really trying to optimize. For the vast, vast majority of individuals, motivation is the thing that’s most required to get you to engage in any these mindfulness activities.

[DAMIEN BLENKINSOPP]: Great Ariel, thank you for that, it’s interesting. I certainly agree; a lot of it’s about motivation and accountability, making sure you’re moving in the right direction.

Thank you for all of your tips on Muse and for giving us some insights into how it works.

[ARIEL GARTEN]: My pleasure. Thank you very much for the time. I’m happy to be on the podcast with you.