A couple of cutting edge and very relevant quantified body topics today- quantifying the microbiome and the state of crowd science

We’re looking at the microbiome, which you probably have seen is the big new topic in the health media and news the last few years. Research is increasingly relating differences in our microbiomes to a range of disease conditions, primarily chronic and gut related ones. If you’re already buying the probiotics or prebiotics in the health store – the reason you’re doing that, is for the microbiome.

But what, if anything, do the probiotic and prebiotic products do for us? How dangerous is taking antibiotics – through changes they make to our microbiome? How does what we eat influence our microbiome?

It’s hoped that quantifying the microbiome, understanding what types of bacteria and other things make it up, will provide a lot more insights into our microbiomes – but how far has the science behind quantifying it advanced? How reliable is it? – and can it lead to us making decisions that improve our microbiomes that in turn lead to better health and less disease.

As we’ll see this is really cutting edge currently – and changing fast. But we have an excellent guest today to bring us up to date on all this.

Jessica Richman, is CEO and co-founder of uBiome. uBiome is the largest crowd science, or citizen science driven project to date. uBiome, already the most popular of the consumer microbiome services, is just about to go through a revolution thanks to recently having gained significant funding, and the backing of Y-Combinator as well as many big name investors such as Marc Andreeson and Tim Ferriss.

Jessica, herself, has an impressive background having started and sold her first company in high school… and having accumulated countless scholarships and awards in academic institutions including Oxford and Stanford universities since. Her major interests include network analytics, innovation, collective intelligence, and crowd science.

The show notes, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

Show Notes

- What the microbiome is and how it varies across our bodies.

- The many different aspects of the microbiome (bacteriophage, fungi etc) and why uBiome provides solely data on the bacteria in your microbiome in order to deliver their service at the low $89 price point.

- The different areas of health that the microbiome and its status and and is increasingly being linked to in research studies.

- Different approaches to quantifying the microbiome and their accuracy: cultures vs. microarrays vs. next generation sequencing.

- 23andMe’s model for delivering consumer based low pricing via focusing on genetic SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms).

- The 5 body sites that you get quantified with uBiome (the same used in the Human Biome project).

- How uBiome is avoiding the FDA regulatory landmine that 23andMe got hit with and which forced it to cut down the information, range and depth of services they were providing to consumers.

- Citizen science or crowd science and what it means for the future of science and potentially the medical world.

- Comparing different sequencing methods of uBiome, American Gut and others and progress being made to one common standard.

- What should we be aiming for in experiments we run on our biome? Diversity? different ratios of the different types of bacteria?

- The value of getting a baseline sequencing of your microbiome now to compare with in the future (especially if you should get chronically ill in the future).

- Do probiotics impact the microbiome? If so, how do they impact it? Conflicting anecdotes, research studies and “marketing hype” from all the probiotic supplements and foods now available.

- Personal insights from Jessica on how what she tracks about her own body, experiments that have worked, and her top 3 recommendations for people trying to improve their bodies and health through the use of data.

Give some love to Jessica on Twitter to thank her for this interview.

Click Here to let her know you enjoyed the show!

Lab Tests and Devices in this Episode

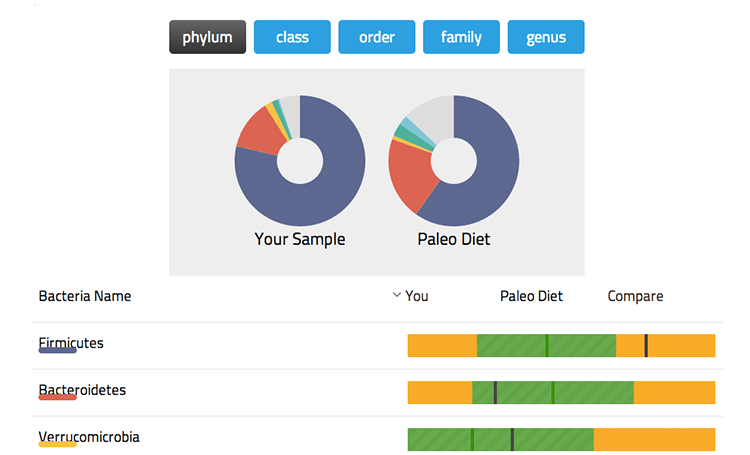

- uBiome Microbiome Sequencing: The lab tests discussed in this episode. These can be ordered by anyone and done from a kit sent to your home.This is a sample chart output from their interface with my sequencing showing that I have more firmicutes and less bacteroidetes than the standard person on a paleo diet:

- 23andMe: The largest and cheapest service for getting your genetic sequencing (a subset of your total genetic makeup).

- American Gut: The other main consumer microbiome sequencing company (not for profit).

- Ketonix: The breathe analyzer for assessing your ketone body levels and whether you are in a ketogenic state. We covered this topic in detail in a previous episode with Jimmy Moore.

Other Resources Mentioned in this Episode

Jessica Richman & uBiome

- uBiome: The company Jessica heads up as CEO, and the largest company you can currently get your biome quantified with.

- You can also connect with Jessica at her personal site, and on twitter @JessicaRichman.

- Why Should Science Be Limited to Scientists? Jessica’s talk at TedMed on why we should be turning to Citizen Science for the future.

- Comparison of uBiome vs. American Gut sequencing approaches: This blog post was written up to explain how the two companies’ approaches differ and why the same sample sequenced by both companies may not directly match.

Other People, Resources and Books Mentioned

- The Human Microbiome Project The original NIH (National Institutes of Health) funded project to first sequence the human biome between 2007 and 2012.

- Ilumina The solution uBiome is using to do their next generation sequencing of the biome.

- 23andMe’s regulatory conflicts with the FDA

- Jeff Leach Jeff heads up American Gut and has published his own self experiments to change his gut and move it towards a more diverse gut microbiome by interacting with Hadza hunters from Tanzania (read about it here)

- Chris Kresser Chris, a functional doctor who works with patients on improving their gut microbiomes, has discussed that taking probiotics doesn’t change the microbiome’s makeup, but seems to impact it in via other changes or modulatory effects.

- Probiotic foods: Jessica says she feels better with Quest Bars, while Damien has noted anecdotal beneficial effects with this Kefir product.

Full Interview Transcript

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: All right Jessica, thank you very much for being on the show.

[Jessica Richman]: Hi, it is great to be here. I am really grateful for the opportunity.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Sure. So to kick it off for you, let’s talk about what the microbiome actually is. I understand it is not just the gut. So how would you describe the microbiome?

[Jessica Richman]: The microbiome are organisms, the microorganisms, that live on or in all of us. And there are many different microbiomes in the body. I think we should take a step back first though and say why is it called the microbiome? What is a biome? So a biome is an ecological area. So in the macrobiome, the biome that we are part of – you can be part of the rainforest, or a desert, or a tundra. And these are environments in which organisms live. And in the body, the microbiome where it actually could be anywhere, not just in the human body, but the microbiome are the microenvironments live in. So if you think about it, it is very different living inside your nose than it is living on the surface of your nose. So inside your nose it is windy, it is warm, it is slightly wet, and there are immune system interactions with human cells. On the outside of your nose it is probably colds, it is dryer, it gets sunlight, there are different kinds of cells that the bacteria are interacting with and if you think about it, it is a very different type of place to live for a bacteria.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you could use the analogy of looking at the world and the jungles, the deserts, and all these different kind of things living in them?

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly, right. And if you think about it the outside of your nose is much more like a desert and the inside of your nose is more like the rainforest, let’s say. It is a very wet environment for an organism to live in. So if you think about it that way, it makes sense that there are microbiomes all over your body and all these spots have very different types of organisms in them and the microorganisms are very influenced by the environment they are in and what can survive in various environments. it is very different, just like plants of the rainforest don’t do very well when they are in the desert. But microorganisms that normally live in the rainforest die off when they are put in the desert. And it is not just bacteria, of course, there are also other microorganisms.

So there are fungi and yeast and all sorts of other organisms that live there and there is this whole ecosystem that we were just never able to see until recently because now it has just become less expensive to sequence the DNA on these organisms, some of which can’t be cultured. So previously you would figure out what was living there by trying to grow it in a petri dish, but that means you have to have the right food, the right conditions, it has to be able to be grown in that kind of environment and not all organisms can be. So now we are finding out things that were just impossible to see before. So now we know more about the microbiome and we have learned that my nose, the inside of my nose, is much more like the inside of your nose than my nose is like my foot, let’s say, because these are very different environments.

Our feet have more in common – the same spot on your body but very different types of places. So the NAH funded a project called the human microbiome project which was sort of supposed to follow after the human genome project to learn about the human microbiome, and they looked at 250 people and they established a lot of the sort of basic technology for doing this. And what we do with the biome is we have scaled up that technology and made it possible for anyone to have access to the same technology to understand what is in their microbiome at various sites and then what to do about it.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Is this like PCR DNA analysis?

[Jessica Richman]: So it is next generation sequencing, which is – there are a number of different platforms but kind of the leading one at the moment is by a company called Illumina, and they make what is basically a camera. It is funny, we just got one, and it looks like a printer/scanner – like an HP printer/scanner combo, one of those things you buy at an office supply store. It looks like that but what you actually do is you put a tiny tube of liquid in it that has the DNA in our case of 500 different people’s microbiomes, and it is seriously a tube that is less than an inch long. And you stick it in there and it is a camera that takes pictures of each of the base pairs of the DNA as it goes along and then tells you what the base pair is. So it is really amazing technology. They have really, they have changed the world.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So just to be clear, is that something you are going to be using or is that what you have used to date?

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, so that is what we use right now. So right now we do next generation sequencing and we have been sending that out to various people to get – we sort of do all the processing and they just kind of – it is kind of like sending out your printing to Kinko’s or something. You prepare the document of what should be in it, and then they do the printing part. We have now brought that in house because we have brought in some funding and we sort of have the opportunity to bring it in house, which gives us a lot more flexibility, it is lower cost, we can do things faster because it is right here. So this is the technology we have been using all along and this enables us to really, inexpensively, make consumer price points for $89 to be able to tell you exactly what is in the DNA of all the bacteria that are living in your microbiome.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so what are the limitations of this? Just a minute ago you were talking about the fact that the microbiome has fungi and bacteria. Today even there are viruses, bacteriophage, viruses that infect bacteria, and all this crazy stuff that we don’t hear about but it is so super complex. So are you just looking at the bacteria aspect of it?

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, so we have the capability to look at fungi and even to do full metagenomic sequencing, which is to look at every organism, all the DNA that is in the sample, whether it is bacterial or human or plant or from the food you have been eating or every bit of DNA that is in the sample. But we currently sell to consumers the bacteria because it is simpler, it is easier to compare, and we have more people who have those kinds of samples. But there are definitely things that we are developing for the future, products that we are developing for the future based on specific other slices of the microbiome, like fungi. And full metagenomic sequencing is really expensive – it is thousands of dollars so it is not really a good – there is this much consumer demand for that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so that people understand 23&Me is pretty well known and they took a similar approach. They are only scanning certain aspects of genetics.

[Jessica Richman]: Well, it is a little different. So 23&Me looks at snips. So they look at our single nucleotide polymorphisms that are specific parts of the human genome that are known to be correlated with specific research outcomes. What we do is we look at all the bacteria. So there are other technologies that some people use that are based on microarrays that will only look for certain bacteria. So instead of – it is kind of an intermediate point between a culture-based method. That is maybe too technical. With culture you say is X bacteria there, yes or no? Does it grow or not? And maybe it couldn’t grow or maybe you did it wrong, whatever so there is some fallibility built into that. With the microarray method you say are any of these 96 bacteria there? And it can check for all of them. WIth the next generation sequencing you can find everything that is there and we are selectively looking at just bacteria because it is sort of priced so that the consumers can pay.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And is this a selection of bacteria I assume there is going to be classification, or a library of what is known well today? Maybe there are just some things that we don’t know there. so does it see everything?

[Jessica Richman]: That’s true, yeah. Well, it is everything that is known plus all the things that we are finding. so there are some public databases of bacteria and what we have done is we have taken the public databases and then added our own and basically enhanced them and so we had it in – they are polydatabases so people upload a lot of junk to them that they think is a good idea to upload and they are not very well curated academically. So we have taken those databases and cleaned them up and streamlined them and added a bunch of things to them to make them better.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, I think what is coming across is that this is quite new and it is exploratory. So the human microbiome project, how long ago was that –

[Jessica Richman]: So that started in 2007 and went until 2012 and we started our company with a crowdfunding campaign, actually, two months after the human microbiome project ended. So we sort of had this – you know, my background is not in biology. It is in computer science and economics and I was doing PhD in computational social science and learning about applied math relating to social networks. And I just saw there is so much interesting information relating to biology and some of the same skills that I was learning could be applied to this new information that was coming out. So we started this project right after the human microbiome project ended. And it is really new. The human microbiome project was really groundbreaking and helped establish this whole field. and you can see the number of scientific papers that are related to the microbiome is on this exponential curve up as the human microbiome project progresses. but we decided to take this technology and bring it to the public.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and so at this stage now, for the consumers, what do you think – what can they get from it, if they get their biome? First of all you have talked about microbiomes. So you do the gut, you do the nose, genitals, mouth?

[Jessica Richman]: Mouth, skin, and genitals. Those are the ones we currently do. So we have the technical capability to do other sites and we are going to be launching some products that relate to the skin, for example, between your toes and things like that. But at the moment we do those five because those are the five that were in the human microbiome project. So it sort of gave us a basis for the data and sort of sample collection procedures that have been well validated. Yeah, we sample all those microbiomes of those five different sites. Then what consumers can get out of it is they can see what is in their microbiome, first of all, and then how that compares to other people and then how it compares to existing studies of the microbiome.

So right now in our [user interface – 00:12:50], it is very nerdy. It is very [inaudible 00:12:52] from our crowdfunding campaign, but you can see what are your bacteria, how does your distribution compare to other people’s distribution of bacteria, and then you can learn a little bit about each of the bacteria that are in your sample and how they relate to existing studies, which studies involved with which bacteria we are building right now. And this should be out in the next few months, like two or three months. We are actively in the development process and this is software that will go a step further and give you much more data analysis about what is in your sample.

The cool thing about doing it now is you are basically biobanking your samples. So if you sample now it is not like it is lost and you missed your opportunity, it is the only way to sort of grab what your microbiome is like now and then as our interface gets better and as our data gets better that sample gets better but you can also compare it to future samples.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so it is the same as genetics. Basically you will be able to re-examine that same sample and still be updated?

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly, but actually we store the data so we don’t need to re – we can resample it later if technology changes completely and we need to totally resample it we can do that. but we also have the data from that sample and let’s say you sample now and you are like, ‘Oh, that’s interesting, my bacteria are fine.’ But then six months from now you want to make a radical change in your diet and you said, you know, maybe I need to cut out dairy, I don’t know, and you try that. Then we can sample afterwards and we can show you the difference between those two things. And we will have the earlier sample so we will know what it was like before.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so you are talking about things that influence it and I guess it is quite an important point to mention that your microbiome can change. There is a lot of emphasis on the gut these days. that is the one they talk about most in the press and stuff so i guess it is the one with the most research?

[Jessica Richman]: It is, it is the one with the most research and it is also the one with the most – it is the richest environment for bacteria and that is why the most research is done there, because it has the most bacteria of any site in your body. And also obviously because that is where you process food and waste, and it has the most biological activity relating to all parts of your body. So they found really interesting connections between that and the brain, for example, that are not what you would expect. There are really interesting relations between the microbiome and depression or autism or things that you might not expect, but they don’t say that, for example, about the nose microbiome because that is just less likely.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so in terms of you just mentioned a few diseases and conditions – there were things like obesity mentioned, diabetes, acne, allergies. There is quite a range which are now linked in some research to the microbiome. How far along do you think that is? Do you think that has got quite a long way to go or do you think it is interesting for someone to say, who has one of these conditions, to get their microbiome done?

[Jessica Richman]: I think it is not that far off, and I probably think that because this is our field and what we are working on and we know the possibilities, that things can happen quite quickly. I think it is not that far off because we’re collecting all this information that can be useful in actually doing something about it. At the moment this is a consumer product and it is not intended to treat health conditions or diagnose health conditions, but we will have the information and when we do find something interesting we can then pursue the proper channels in making sure that it is available to people who have health conditions and need it.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so I mean, you stepped on the 23&Me landmine.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly. Well, we didn’t step on it. We were collateral damage or something.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you said something very important there, it is a consumer and not a medical product. How is that evolving? Are there things that you have to do or are there limits? Can you give us an idea of how you are going to go over that?

[Jessica Richman]: We try to be really careful. And we try to be careful because we don’t want to get into the trouble that they got into, but also because there is sort of a really important public health responsibility to not give people information that is dangerous, poorly understood, that will lead them to do things that are bad for them without understanding why or mistakenly thinking they understand why. I think it is really important to do that. So we are careful to – we are sort of pursuing a two-prong strategy.

One is for things that involve diet, wellness, health, and people’s curiosity about science that is fairly safe in my view. And then things that involve serious health conditions, we are being much more careful with that and we want to make sure we have much more validated information and that we go through the right channels and that people have expert consultation with their doctors or even at the very least with clinicians doing research to share that information. I think it is just a matter of trying to be conscious. And there aren’t any written rules. There is nowhere that we can say, ‘Oh here is where the line is, let’s be careful to make sure that we are on the right side of it.’ But we are just kind of using our judgement at this point to make sure that we are thinking through the issues and trying to be responsible about how we give people information.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, good to hear you are thinking ahead. So we talked a little bit about things that can affect it. Do you know of any clinicians that are starting to either take this themselves or maybe send their patients to give them an idea? A lot of clinicians are trying to tackle things which aren’t very well treated or documented, like dysbiosis and IBD, all of these kind of gut issues, which at the moment is hard to find some clinicians who can say this is the exact approach to fix this. It is not coded and it is more of an art to say the least.

[Jessica Richman]: Right, there is no standard care for a lot of things. And that is difficult because patients are then left without a good answer, even though he went to the doctor to try to get help. I think what we’re doing at the moment is that this is not a diagnostic test. It can’t be used by a clinician, and I sort of want to underscore that. But we haven’t evolved in clinical research, so if a doctor wants to put together a research study of their patients or the participants that they solicit, we partner with them and we provide them basically with a consumer produc. But since they are a clinical researcher they can have a study and they can sort of design this study the way that they want and then communicate with their participants the way they want, which is a way to sort of frame it experimentally so that it is not basing a diagnosis on it or giving medical advice based on the test, but they can use it to learn things about the entire population of people that they are working with.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, and it can better inform the doctors instead of guesstimating all the time.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly, right, And it can also press for publishable research. Some of the doctors are doing really cutting edge things and they want to add this to the repertoire and say oh, this is really interesting when i compare patient group X to patient group Y I notice X has this interesting thing, their microbiome, that is publishable research. So we are contributing to science through clinicians who were doing clinical research. A lot of the doctors that are sort of on the cutting edge also do research as well as treat patients, so they can kind of wear both hats.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, right. I know that this kind of connects with the topic that you are a big fan of, the citizen science?

[Jessica Richman]: Yes, don’t get me started!

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: We will definitely put a link to your TED Talk on that for background, but briefly, what is citizen science? What is that about?

[Jessica Richman]: Sure, so citizen science is a word for non-scientists, non-PhD researchers who work in academic labs. Sometimes they are people who have PhDs but aren’t researchers. They are contributing to science in some way. It started with – and actually, it is really interesting. So Susan Science, that term and the use of that concept, was started by ornithologists, who study birds. And there aren’t enough ornithologists who gather data about all the birds. So there are a lot of amateur birdwatchers who contribute to the science ornithology by spotting birds in various areas or by reporting on the things that they have seen.

So it started out there but this concept of involving the public in research is really just a type of crowd sourcing. So the term we use for uBiome now is crowd science, because I think it sort of communicates the fact that this is not about their citizenship or what country you are part of or whatever, but the idea that the whole crowd can be a part of science. And not just data collection, as in bird watching, but also hypothesis generation, funding of science, evaluation of science. We haven’t done all these things yet, but we really want to.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That is interesting because uBiome is basically – you just brought up a whole bunch of things. And that is what uBiome is.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly. So our goal is to use the fact that people are interested in the microbiome, that it affects all of us, that we all sort of are potential research subjects because we have a microbiome and that we do think that change, to allow us to change the way science is done and to have people fund science, evaluate science, learn about their bodies, and contribute that knowledge to help others, and i think that it is really a change in the way science, which is this very institutional system, it is very much like the change from only four broadcast channels to like YouTube.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, that is a perfect analogy. It is about – this is taken from your talk, but it makes perfect sense. It is like participation – a good example I thought you gave also there, I mean, obviously YouTube allows anyone to participate and everyone sees people putting forth innovation, innovative content, and that then goes to TV and other places, which is a good analogy. If TV was science, now and again they will find something in the crowd which is useful and they will integrate it, so it is kind of like taking that participation.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly, and then it makes it something everyone can do. I mean, YouTube is full of teenagers covering pop songs or something that would never have even been possible to be shared before because you would never waste your really expensive broadcast spectrum on something like that. But you don’t know who is going to be the next pop sensation and you can find that. And it is kind of a trivial example, but you can see that in the world of science and you don’t know who will come up with a really interesting discovery. And this was part of the theme of that talk, that I think it is not – a researcher who is paid to study an area is obviously passionate about their work and is an expert and what they are doing is really valuable. But a person who is suffering from that condition is also really valuable and I feel like they have been totally excluded from the system at this point and integrating in their own knowledge about themselves can add so much.

This is an example that I didn’t give in the talk but I think is really interesting. A friend of mine is a spinal cord researcher and she told me – I should probably verify this a little bit better. What she told me was really interesting. She said that the field of spinal cord research changed really dramatically when – most spinal cord researchers are not spinal cord patients. Most of them are not – they kept on working on trying to get people to walk. What they finally realized after there was a researcher who was a spinal cord injury patient who did a survey to say, ‘What do you actually want us to be researching?’ And it turned out that most spinal cord injury patients have accepted the fact that they are not going to walk, and that is sort of just the way it is. But what they want to be able to do is all the things we do. They want to be able to get around easily, they want to be able to sit comfortably. They want to be able to socialize, they want to be able to go to the bathroom comfortable.

They want all the things that we take for granted. And that is actually what they care about, not learning to walk again. That would be nice, but that is not affecting their lives as much as just basic quality of life now. And that really touched me because I thought, ‘How much time and money is spent researching the wrong things that patients don’t actually care about?’ Because it sounds really good. We are going to make them walk again. It just sounds like you are the great savior that is going to come in and solve all their problems. But maybe they want totally different problems solved.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and you see a lot of communities which get kind of negative and fed up with the way things are being tackled and they are also the most motivated as well as all the passion and motivation because obviously it is effecting their lives. So if we could harness that motivation and passion that could obviously help push things forward. But it seems like citizen science, what it needs and what you spoke about is basically helping to organize and structure this crowdsourcing because obviously if everyone just goes off in their different directions and it is not controlled that is just a mess.

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, I think so. And I think our role is to sort of create the infrastructure that makes it easy for people to study things. And that is what we want to do that helps us business wise and it also just helps us make that change in the world happened have the average person be able to have access to these cutting-edge DNA sequencing technologies that most people don’t have access to just by making it as simple as you buy a kit, you answer some questions, and then you get some results.

So I hope to see this in other areas too because I think there are so many things that are sort of very disorganized in the approach of patients who have them or even just subjects of interest, or things that people are just curious about and that greater scientific establishment is not super concerned with, whether [inaudible 00:25:28] is good for you, or something like that. Nobody cares about that because they obviously have much more important things to worry about in terms of public health but it is interesting to people. And I think people should be able to fund the research that they either desperately need or that they just are curious about, and I think that should be open to everybody.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I think that another analogy is that if you look at businesses as entities and the way they have evolved over time. It used to be from top down they would design products and push them on the consumers and that wouldn’t work so well but they have become these marketing – they are a lot more integrated, they look at customer feedback and in a way you are talking about applying that same concept to science as well, having this feedback mechanism which helps to direct the research also from the end user or the end benefitter.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly. I think that is true. I mean, it is sort of changing from the sort of theory of the firm and having this institution that broadcast things out to people, to this network where people can interact in a much flatter environment. And I think that is very beneficial for innovation because it will help us, the best ideas. This was something we were talking about, we work with some researchers and they were saying the best ideas are not the ones in our building because you can’t hire everybody in the world who is thinking about your problem. The best ideas are out there in the crowd somewhere and the idea is to bring them in.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well, it is very exciting. I hope you help to push that movement forward, obviously.

[Jessica Richman]: I hope so, too. It is something I care a lot about.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well, it is these kinds of things which really change. It is a revolution rather than just an evolution. So that needs to be given efforts. So the other thing I wanted to touch on is obviously there are a lot of different things that can affect the microbiome. Some of the things we have spoken about so far is diet, right? Everyone kind of understands that diet can impact it. And we look at things like probiotics, prebiotics, dietary fiber, high-fat versus low-fat diet, artificial sweeteners have been in the news recently. How do you kind of look at the diet influence and how far – how much understanding we have? Is it a big impact? Is it a major impact? Do we have to look broader than that?

[Jessica Richman]: That’s a good question. So it is a major impact but the questions are teasing. it is a very complex impact. So the question is – and this our science team, is trying to figure out teasing apart those different effects, people who eat very healthy diets also tend to exercise a lot and be young and healthy otherwise, and sort of have this cluster of things that is sort of separating out what is the effect of diet. What is the effect of exercise?

And we are lucky with the microbiome – it is sort of a great feature, the microbiome, that changes over time in response to a change – we can say, ‘Okay, you are not much older and you are still equally healthy but you have changed your diet and here is how your microbiome changed in response.’ And we can see those differences. That is very interesting, but there are a lot of effects to tease out. We definitely see huge differences. Now that we have looked at thousands of these we can say, ‘That is a vegetarian,’ because you can just kind of tell by looking at the microbiome. Which is really kind of fun, actually.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: My results are actually kind of weird, like compared to everyone’s.

[Jessica Richman]: Oh tell me more, interesting.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I have got very high, very low [inaudible 00:28:25] and very high [inaudible 00:28:30], so like 78%.

[Jessica Richman]: Interesting.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so I was actually looking at the American –

[Jessica Richman]: The American Gut.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, the American Gut and Jeff Leach and what he is doing in Tanzania with the hunter-gatherers. Could you give your perspective on that? I am sure you are aware of that more than I am.

[Jessica Richman]: It is very interesting. Their scientific project out of the University of Colorado that is working on some similar things, and I think are differences that were not just America and not just the gut, so I said that was sort of a very easy comparison to make in that way. And also they are non-profit and part of an academic research project and we are for-profit. But I think there are also some technical differences in terms of the sample, collection techniques, lab extraction techniques that are really technical, but suffice to say there isn’t a standard microbiome extraction method and we both used well-documented, very much validated research methods, they are just different methods.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well just on that, because there was a little bit of controversy on that when someone published that. Could you talk a little bit about that? Is that because there are differences in samples? Are there differences in the approach? Because the two samples came back a little bit different from the two companies.

[Jessica Richman]: There are a number of differences. They came back a lot different and I think the reason is – there are a few things. We used a different sample collection technique so when you sample with the American Gut they take a swab and they rely on the swab drying out so that it doesn’t change in transit. Basically, you just send back a Q-tip, or a sterile swab, in the mail. And it isn’t preserved in any way and there is nothing to freeze the DNA at that point in time. So it leads to – there is an argument to be made that it leads to overgrowth because things are growing as you are transiting in the mail to their lab and before the sample is processed.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And maybe some things are dying as well?

[Jessica Richman]: Well, dying is okay, because they are there. When you look at the DNA, dying is okay but it is other things from the air landing on it, growing in it, and then you think that was what was in the gut, not what was actually – you don’t know what happened after the gut. And everything that is there you see is there. And they do some correction for that with bioinformatics, but it just leads to different results. The results are biased in different ways.

Then as far as the actual extraction technique, we both use slightly different – and this is too technical, but we use slightly different kits for the extraction of the DNA that leads to different results, but it seems to me to there is a reasonable way to translate between the two based on that part of it.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, and you had a blog post on that.

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, we did a blog post on that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: If people are interested in the technical aspects of that.

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, we did a blog post on that and I think going forward it would be – one of the things we are really interested in is having a more standardized method so that everyone is kind of on the same page about what that is. And I know there are some academic standards with this, but we would love to be involved in that and do some comparison studies and sort of see how they compare. Because it is in everyone’s interest to have a standard for how microbiomes are measured.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, and they have that now for DNA, right?

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you just have to do the work, the collaboration to get to the same point?

[Jessica Richman]: Well, everyone has to agree. And getting academics to agree on things is really an emerging field. I think this has happened in many emerging fields with their different standards and everyone thinks their standard is the best. So us being no exception to that. So I think we are a little ways from having a translation between the two methods. I think that will be much more important as we move towards clinical results, where you actually want to get the same result everywhere that you do it. Where as in academic research labs this is far from uncommon – only 10% of the studies in the biological sciences can be reproduced. So this is not something that has never happened before.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and this is a common point that comes up in this podcast, whether it is blood samples or heart rate variability, there are different standards at the moment because a lot of this stuff is still new. So I guess the rule for consumers if you start with uBiome, stay with uBiome so that you can compare. If you start with American Gut, stay with American Gut because otherwise you can’t compare your results.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly. And we wish they were more interoperable, but that is the current standard. I mean, the goal of American Gut is a little bit different too. Their goal is to map the American Gut, what is in it, which is a really interesting scientific goal and very laudable, but that is different than our goal, which is to give consumers valuable information about their own microbiome while contributing to science. So that is a very different goal because our main focus is on giving the individual what they want and then letting them have more control over science.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So going back to Tanzania and [inaudible 00:32:55] because what was interesting there is it is difficult for us to know what we are aiming for, what is good, what is bad in the microbiome. You are doing interesting stuff at uBiome because you have these categories which, if you don’t mind explaining quickly, what you do there.

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, of course. So we compare – we sort of pick – so in our new version these will be much more flexible than they are right now, but what we did not for this first version is we have specific categories of people that have very different microbiomes from each other and you can compare yourself against them. And you can say here is my comparison against vegetarians, people on the paleo diet, people who have taken antibiotics recently, people who drink a lot – exactly, people who drink a lot of alcohol.

So we sort of compare against those categories and those are interesting ones that we sort of see a really dramatic difference right away, so it is very interesting for people to do that. Compared to hunter-gatherer tribes, it is really interesting. I was actually talking to someone and we do research projects for researchers also. I was looking at vaccines in the developing world and we usually come at this from such a totally different angle because people assume that people in the developing world had the perfect gut and if we could only go back to our hunter-gatherer ancestors we would all be so healthy.

And I suppose that is true for chronic diseases, diseases of civilizations, but it is not true when you are very sick with acute illness because your water isn’t clean and you want to be vaccinated against it, for example. So it was really funny to have this conversation with this vaccine researcher who was saying this is really interesting. You are assuming that the gut of people in the developing world is better, but maybe that isn’t true.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: But yeah, it is just true. The whole point is they are looking at the [inaudible 00:34:36] and other people because supposedly haven’t changed much over time. I think the most interesting thing that I saw there was the diversity. How important do you think diversity is because the argument was that the [inaudible 00:34:45] have a much more diverse microbiome, so that is good. Is that true? Is that for sure?

[Jessica Richman]: That is such a good question. Many studies have shown – I will answer this a bit eventually. Many studies have shown that there are positive outcomes correlated with diverse microbiomes. For example, there have been studies in elderly patients that when they are sicker, when they have less diverse microbiomes, and perhaps that is part of the moving to a more institutional diet as you move into assisted care or assisted living facilities or something. Part of that is the microbiome becomes less diverse and that is worse for you. There has been a lot of research about how eating a variety of foods, sort of following [inaudible 00:35:28] food dictums will make you have a more diverse microbiome and that is associated with a lot of healthy outcomes. So there is a lot of research and I think that it makes a lot of sense that it would be healthier.

There is also research about that a lot of health conditions are because there is a cornerstone species you just can’t get rid of, for example, C. difficile infections are one species that has sort of taken over your microbiome and that makes you very sick. So I think the evidence is there and the diversity is good, but the scientist in me to some degree used to say this is good and this is bad because there is always some kind of exception to that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and like we said before it is very early stages. So it is just kind of indicators. So I guess an interesting thing when I am looking at your biome now and if I compare myself to people taking antibiotics. Antibiotics are known to kill of bacteria of course and part of your biome. So everyone can kind of see, yeah, that is not a good thing for your biome. I think that is kind of commonly accepted now. So that is one interesting thing you can do in your biome, and sort of compare yourself to people taking antibiotics. Am I more diverse, am I less diverse, or the same. And to give you a rough idea of how healthy you are?

[Jessica Richman]: Right, what we want to do – I wouldn’t make the claim that it makes you more healthy but we can definitely say that with antibiotics, how were you before you took them versus after you took them. I think that would be really interesting. So it is not just you to the population, it is you to yourself. And so you get a sample now, a sample after you take antibiotics, and and then see the difference between the two. And then sample a few months later and see if you have gone back to where you should.

Because most people bounce back to where they were, where they feel fine and it sort of looks like that microbiome is very similar, but maybe that is not true of you and it would sort of be the only way to tell. So there is a lot of really interesting stuff there in terms of tracking your own health and sort of having a baseline that you store now, so you find out, for example, that you have Lyme disease or some other health condition that makes you take chronic, long-term doses of antibiotics, you kind of know back where you were when you started.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, and then at least you are like okay, I was healthy at that point, maybe I should try to get back to where I was in terms of my microbiome. So at least you have –

[Jessica Richman]: And some of this is all in the future but the part that is not in the future is we can store the sample now and we can tell you what is in the now. And the part that is in the future is okay, how do we get you back to where you were and how do we know what is a good change and what is a bad change. Those are all the things we are working on really actively and we should have some answers, not in the next few months but in the near future. but there are just a lot of really interesting things we can do once we have the data stored then we can kind of have a basis for comparison.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So there are a whole bunch of people doing experiments right now, and I think we can call that citizen science or crowd science, right – there are people taking dietary fiber. I am quite amazed because I just got back to the US and I am going into like Whole Foods and places, and probiotics is huge. It has grown out of proportion and you see even in the drinks, like half of the drinks seem to be probiotic drinks now. So obviously that is really, really pushed but to some people, like clinicians like [inaudible 00:38:20] if you know him, and he is like well, there is evidence to say that probiotics don’t change your microbiome that much. So in terms of experiments, you might do one yourself or you might think are kind of interesting, what kind of things would you think?

[Jessica Richman]: Oh, this is so good. So one of the things that we would love to do and that we are sort of trying to set the infrastructure for is to test out different probiotics on different people. Well, we won’t test it on them – they will take it and then we will test them and you know, of course, this will be part of us researching the effects of the probiotics on the individual. This will be part of a study where we can compare like to like. Like people taking like probiotics and sort of their outcomes. I think it is really interesting.

There are a lot of studies that show that either probiotics are mixed or that they don’t work. But then there are a ton of anecdotes from people, and we hear from them all the time, who say this changed my life. This actually worked. And I don’t think that they are all making it up or they all – it is all the placebo effect. I think it really is having an effect on some people. But the question is who and under what conditions and how do you know and what is it doing. And these are all really good questions.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, I guess from what we know it is not actually affecting the microbiome it is affecting something else. I mean, you call it the microbiome but maybe it is not the bacteria or who knows.

[Jessica Richman]: Right, maybe it is not the bacteria. I mean, it is an ecosystem there, right? So it could be –

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Maybe it is protecting you from the yeast overgrowth. Or who knows?

[Jessica Richman]: It could be, right? Exactly. Maybe what you want is not the presence of that bacteria but the absence of something else. I think that part is probably the easiest. I think if it is doing something there is some mechanism, right? So that part we can figure out later. I think it was the most immediately useful to people who have questions or problems and want to take something but don’t know what or don’t know if it is worth it for them to do it. It is just to see what probiotics have what effects on what people. I think that would be really valuable.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I think it is really interesting in these areas where people are spending a lot of money. It is obvious to me that people are now spending a lot of money on probiotics and they are starting to spend a lot of money on prebiotics and you see all the supplements now and the people talking about resistant starch. If people are spending money on these things, I think it will be really useful when data actually starts coming out to prove it. The marketing always goes way faster, the hype goes way faster than any of this stuff really, and who knows – it is anecdotal. For myself, I think i do better with [keffir 00:40:33]. When I come to the US I love the [Keffir 00:40:36] so I will drink that and I tend to feel way better with that. But I have heard other people say that but who knows why or what that is about.

[Jessica Richman]: So don’t you want to – I mean, don’t have you have this natural drive to be like, why, why me? Who, and who else?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I will be doing another sampling of uBiome this month to see if that has change anything because I have doing more of that lately.

[Jessica Richman]: So I started eating – I don’t know if you ever eat Quest Bars, which have prebiotic fiber and it is [inaudible 00:41:02] invasively so they are indigestible fiber that is not supposed to count as carbohydrates. I feel differently when I eat them versus bars that have maltodextrin or something in them, and it is sort of obvious, digestible carbohydrate. So it is really interesting and we get to do a lot of experiments around here and just sort of see what the difference is.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So Jeff Leach is arguing that dietary fiber has a bigger impact on changing your microbiome based on his self tests. And what do you think of that?

[Jessica Richman]: So that is interesting. There are a lot of things you could say about that. And one, there are all those sorts of things. So I think the answer to all these thing is sort of more research. That is interesting, and a lot of things have been discovered by scientists looking at themselves and saying, ‘Huh, that’s interesting. I wonder why that happens.’ Or when I do X, Y happens, but I think you really do need – and what the crowd science lets you do and what the power of the internet lets you do is say okay, that is an interesting hypothesis. Now let’s have a thousand people test that and see what happens. Then you can find an answer to it. So I think that is the goal, and that is what is great about crowd science. It is not my opinion versus his opinion, it is his hypothesis versus the data that we see.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. I guess a good principle for the people at home is before you do anything get your microbiome done so that if you are going to take probiotics or you are going to take resistant starch or prebiotics. At least you can see what has changed, if anything has changed, especially if it has any health impact. Especially a negative one, and you want to kind of go potentially back to it in order to reverse that.

[Jessica Richman]: Right, exactly. Or even just to have it banked so that then in the future you will be able to win the science of therapeutics and diagnostics is caught up to the science of just processing the samples and the data will be there exactly.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So on that point, basically how stable do you see the microbiome in terms of we often talk about how often is it worthwhile and it adds value to track the data? Because it is not that expensive now, microbiomes, but it is relatively cheap and I assume eventually it will be even cheaper. But how quickly does the data change? We know that the microbiome changes but how long is it worthwhile?

[Jessica Richman]: We haven’t done the study. It would be really cool to just test everyone’s microbiome for a day, test 100 people’s microbiome for a day. And we haven’t done the study every day for like two weeks. We haven’t done the study yet but we have talked with certain partners about doing this. And we may be launching something about this. But there are research studies that have been done on this and there is sort of a change every two weeks for if you make a major change, if you change your diet you will see it within two weeks. Antibiotics of course act much more quickly but if you have a dietary change or a habit change you will see it within two weeks.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: When you say a habit, what could that mean?

[Jessica Richman]: Let’s say you start running marathons or something. You start training for a marathon –

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Exercise, or –

[Jessica Richman]: You exercise, you move, you travel to a different country and eat completely different food. I suppose that is a dietary change too, but you drink different water and it may not be that consciously you are changing your diet but you are in a totally different place.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: We are still talking about diet a lot, but actually just if I am living in another country, it is the fact that I am touching things, if I am living in a different environment where the bacteria could potentially be different, or if I am living with a new partner, for example.

[Jessica Richman]: Right, well probably not your gut microbiome but definitely the oral microbiome changes when people start kissing a new person. So that makes sense.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and the genital microbiome I assume, too.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly, the genital microbiome as well. We do collect genital samples and we do ask questions about that, and it is really interesting. We are adding data insights for the other sites as we do for the gut microbiome, and it is really interesting.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I guess there are less people doing genitals because it is a bit more of a politically sensitive topic.

[Jessica Richman]: Yes, that is sort of it. Also, we sell it in a pack with the other sites. So yeah, I think there are definitely less people doing it but it is still kind of interesting, the kind of insights that you can come up with because you kind of see how people’s habits – and it may not even have entirely to do with sex, it may have to do with women after menopause, how is your microbiome different? Or different parts of your menstrual cycle, or in men if you are circumcised or not. Or if – you know, just sort of other things that are not directly related to sexual activity but have to do with your own body and how it changes over time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, this is a fantastic subject. I would like to ask you –

[Jessica Richman]: It is always great to have genitals and mouths on the podcast.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: For my next workup I want to get the whole thing but whatever, I would like to find it all out. I am not bothered about political sensitivities. So what do you think will happen in the next five or ten years in this area?

[Jessica Richman]: Gosh, I think it is going to be really exciting.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: What are you excited about?

[Jessica Richman]: Oh, there is so much I am excited about. So I think there is going to be a real explosion of therapeutics, the proper word for this, but let’s describe that in a little more detail. I think that a real explosion of drugs, probiotics, diagnostic tests, and just really taking this data and doing something useful with it that helps out specific groups of people either with serious health conditions or even very minor health conditions like acne or athlete’s foot. I think there will just be this explosion of valuable products that come out of this kind of data. And I am really excited about that because I think there are a lot of really amazing problems we all have.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So out of interest, how would a product develop or work with you?

[Jessica Richman]: We do work with researchers that are doing this kind of thing and basically what we do are really big studies about specific questions. These really big study about specific questions, someone is looking at dandruff or if they are looking at athlete’s foot or they are looking at heart disease or autism or something, sort of a major – something with much more important consequences. We designed a study with them and then we partnered with them and they use our research techniques. And depending on the type of study, they will often just use our kits where we handle the whole study process for them. And they basically give the participant the uBiome product and then they also share the data so that they can use it for academic purposes to publish a paper about it.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That feels like a great model. That is real crowd science.

[Jessica Richman]: It is crowd science, exactly. And what is unique and what I really like is that in almost all cases the participant gets their own data too, which is really unusual in scientific studies. Usually you participate and maybe you even get paid to participate but you never get your own data. And I have never heard of a study where you get your own data. But here the participant gets to do their own study also at the same time. Their data is banked and they can access it later. They can do whatever they want with it and at the same time they are contributing to a scientific study that they find interesting.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: The other exciting news for you guys is you have joined Y Combinator with [Anderson and Co. 00:47:52] and you have obviously got big investments now in terms of microbiome project and you are by far the biggest investment. And so correct me if I am wrong, but what does that mean for you and where you can take the company now?

[Jessica Richman]: So what we can do is we can scale up and we can make sure that the experience is as good as possible for the user, so revamping our website, revamping our boxes, and making customer service better. Like, all those sorts of things are just sort of making the experience better for people. But we could also be able to analyze the data in more detail and come up with really interesting insights for the participants so they could get valuable information. That is what that money is for, to sort of give us the resources to make things better much faster.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And a couple of personal questions before we finish, that would be great. What kind of data metrics do you track for your own body? Anything like the microbiome, anything else on a routine basis?

[Jessica Richman]: That is a good question. I track all my food in My Fitness Pal, me and like 25 million other people or something. It has got every food – you know, if you travel to China there is like the fast food chains that are in there too. It is sort of like every possible food.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So are you taking photos? Or how are you doing that?

[Jessica Richman]: No, I just enter everything.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Have you got a special app or anything that you like?

[Jessica Richman]: I use my fitness pal, which is the most popular one. I am probably in there six times a day logging everything I eat. And then I also do lots of little experiments with myself in terms of how much protein I am eating, how much fat I am eating, and I just started using [keto sticks 00:49:22] recently, and I had never used those before.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, oh, I just got – do you know the ketonics? I just did an interview, the last interview, but anyway the ketonics allow a slightly better correlated – because it measures your breath which is more correlated with the blood levels.

[Jessica Richman]: Awesome – I was looking at the blood kits also and they have those.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: They are very expensive.

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, they are very expensive. maybe that could be a business expense, I don’t know. Anyways, I am starting with the sticks and just sort of sampling and seeing how it can correlate how I feel with ketosis. If I feel warm and tired, then that is probably because I –

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Are you going to be trying intermittent fasting or anything like that?

[Jessica Richman]: I might. I gained the startup 30 so I think I am trying various things. So we will see, intermittent fasting is really interesting and I don’t think I will do the warrior diet because that is the one where you eat once a day and I feel like I would just sort of keel over. But it is really interesting and I like that our users are generally people who are interested in these kinds of things and I like that we can bond over our various weird potions that we are eating and trackign about ourselves.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So what has been the biggest insight that you have learned about your biology through doing some kind of tracking or –

[Jessica Richman]: That is a good question. That is a really good question. I think in terms of the microbiome, I think I have sort of – my cofounder is a lifelong vegetarian who has never eaten meat in his entire life. And his parents were vegetarians and he hasn’t eaten meat. So his microbiome is very different than mine because I have sort of been an omnivore my whole life and it is really interesting to see the differences between people who share a lot of environments in common but eating very different foods, so I think that was a really interesting insight. As far as tracking myself over time, I think I am lucky and that I don’t have a health condition that sort of gives me an unusual microbiome. Mine is very normal so that hasn’t really shown up very much in the things that I am doing. I am tracking a lot of these dietary changes, which I just started doing, so we will see how they go.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well, that is a good point you bring up. Someone could have a microbiome done and then if they fit straight in the middle of the road, then it is probably not a bad thing.

[Jessica Richman]: Exactly, it is a very good thing.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It also just depends on how extreme the experiments you are doing on yourself are.

[Jessica Richman]: Right, exactly. And I think I am just sort of dipping my toe in the water of cool things people can do to track their health, but there are definitely users who do much more interesting things and sort of want to see the effects of them.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so what would be your number one recommendation to someone trying to use some form of data to make a better decision about their body’s health and performance?

[Jessica Richman]: I think there is sort of advanced versus not advanced. So I think the very basic thing is tracking what your food and exercise, it really changes your behavior dramatically. And I have noticed this and it is a very obvious thing and advanced quantified self people are going to be like, ‘Ha ha, I have been doing that for 20 years.’ But for the average person I think it really makes a big difference because you just start seeing – you don’t want to eat junky food when you know you are going to record it. And you start seeing how good you feel when you eat certain foods versus other ones and I think it is really motivating and it is really disciplining.

So I think that is sort of the basic recommendation. I think advanced recommendation is sort of don’t be afraid of scientific literature. Working with scientists and as a scientist, you see what goes into scientific research and you see that it is this really messy field where people are trying different things and sometimes they work and sometimes they can’t be reproduced. So don’t be afraid to delve into literature and see what is there for you and then try to make it work for you. And don’t sort of take it as received wisdom, that it has to be exactly right.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, that is a great point. Thank you, both of those are great point like the psychological benefits and accountability. I think that is probably one of the biggest things that is happening right now with all the devices and everything, just reinforcing behvaiors.

[Jessica Richman]: Yeah, I think it can’t hurt and it takes a little bit of attention, but I think it is attention well spent because it helps people learn to track themselves better and learn to understand what is going on when they feel a certain way, what is likely to be causing it. And I think it is really beneficial.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Jessica, thank you so much for your time today. I know you are very, very busy at the moment so it has been great that you have made the time for the show.

[Jessica Richman]: This was so fun, I am so glad. Thanks for taking the time to talk with me. This is really great.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thank you very much.

[Jessica Richman]: Awesome, I will talk to you later. Bye.