[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thomas, thank you so much for joining us today.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Thank you.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I’d like to start off with basically kind of an overview, because you are putting for a different theory of cancer compared to that that’s been the reigning theory for a very, very long time now. Could you describe the differences between the two theories, and what is the basis for your new theory?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, it’s not that my theory is new. The theory was initiated in the early part of the last century, in the 1920’s through the 30s and 40s, by Otto Warburg, the distinguished German scientists and biochemist. It was Warburg who found that all tumor cells continue to ferment glucose in the presence of oxygen. Put it this way, lactic acid fermentation.

This is a very unusual condition that usually happens only when oxygen is not present. But to ferment in the presence of oxygen is a very, very unusual biochemical condition. Warburg said, with his extensive amounts of data, that the reason why tumor cells do this is because their respiration is defective. So, in our normal bodies, most of our cells generate energy through respiration, which is oxidative phosphorylation. And we generate ATP this way.

But cancer cells, of all types of tumors and all cells within tumors, generally have a much higher level of fermentation than the normal cells. And this then became the signature biochemical defect in tumor cells. And Warburg wrote extensively on this phenomenon, and presented massive amounts of data – he and a number of other investigators.

But what happened after Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA, and the findings that genetic mutations and DNA damage were in tumor cells, and the enormous implications of understanding DNA as the genetic material, this just sent the whole field off into a quest to understand the genetic damage in tumor cells. And it gradually became clear to many people that cancer was a genetic disease, rather than a mitochondrial metabolic disease as Warburg had originally showed.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so when you were talking about the energy and respiration of the cells, just a minute ago, that was actually in fact the mitochondrial respiration, and energy generation from mitochondria within cells.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: That’s correct. That’s correct, it’s mitochondrial. It’s an organelle within all of our cells, the majority of our cells – erythrocytes have no mitochondria, so they ferment. But the mitochondria are the organelle that dictates cellular homeostasis and functionality, and provides health and vitality to cells in our organisms, and ultimately our entire body.

And when these organelles become damaged, defective, or insufficient in some way, cells will normally die. But if the damage or insufficiency is a gradual chronic problem, the cells will resort to a primitive form of energy metabolism, which is fermentation. Which is the type of energy that all cells had, all organisms had before oxygen came onto the planet, which was like a billion years ago.

So what these cells are doing then is essentially going back to a very primitive state of energy metabolism, which was linked to rapid proliferation. Cells would divide rapidly and grow widely before oxygen came onto the planet. So what these cancer cells are doing is just falling back on the type of energy metabolism that existed for all organisms before oxygen came on the planet.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Does that type of fermentation type of respiration, metabolic activity, is that originating from the mitochondria, or from the cell itself?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: No, there was no mitochondria before oxygen came on the planet. So this was purely a reductive activity within cells. It doesn’t require mitochondria, it’s a purely cytoplasmic form of energy. Glucose is taken in, and rapidly metabolized to pyruvate through cytoplasmic in the cytoplasm, and then the pyruvate is reduced to lactic acid or lactide, which is called lactic acid fermentation.

And this then could drive energy metabolism, and the processes that can emerge from this type of energy metabolism. But it’s a very inefficient form of energy generation, and it’s often associated with rapid proliferation.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, thank you very much. So, in very simple terms it seems like, basically what you’re saying is, as the mitochondria get damaged they stop functioning, and then the cell goes back to the original form of energy generation, and it’s as if the mitochondria weren’t there any more.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well it’s not that they’re not there. They are there, and they can also participate in certain kinds of amino acid fermentations. They still play a role in generating energy and nutrients for the cell, but it’s not through the sophisticated aspect of energy generation through oxidative phosphoryation. That part of their function seems to be compromised, but other parts of their function can take place. But they’re not generating energy through what most cells would generate energy through, which is respiration or oxidative phosphorylation.

And I also want to point out, it’s not a complete shut down of oxidative phosphorylation. Tumor cells, depending on the grade, and how fast they grow, and how aggressive the tumor is. It is true that some very, very aggressive tumors have very few, if any, mitochondria. So these cells are primarily massive fermenters.

But some tumor cells still have some residual function of their respiration, and they grow much more slowly than those tumor cells that have no function, or very little function, of their respiration. So it’s a graded effect, but the bottom line is the cells continue to grow, but they’re dysregulated. Because the mitochondria do more than just provide efficient energy. They are the regulators of the differentiated state of the cell. They control the entire fiber network in the cell. They control the homeostatic state of that cell.

So these organelles play such an important role in maintaining energy efficiency. And when they become defective, the nuclear genome turns on these oncogenes, that are basically transcription factors that drive fermentation pathways. So the cells are able to survive, but they’re dysregulated.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, which becomes cancer.

So, in what ways are the mitochondria getting damaged. What is the context for this kind of damage that takes place today? Is this a modern phenomenon, because, obviously cancer has become a bigger and bigger target of medicine over the years, and, potentially, it’s been growing. I’d like to hear your view on that.

Is cancer something that’s always been around, or is it something that affects us more today, and how is it that the mitochondria are getting damaged?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, what you said there is referred to as the Oncogenic Paradox, which has been discussed by Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, who received a Novel Prize for his work on Vitamin C and energy metabolism and these things, and John Cohn from England. These people had referred to this phenomenon as the called the Onogenic Paradox. How is it possible that so many disparate events in the environment could cause cancer through a common mechanism?

And when we think of what causes cancer, we think of carcinogens. And these are chemical compounds in the environment that are known to be linked to the formation of cancer. So there’s a whole array of these kinds of chemicals that we call carcinogens. Then there’s radiation can cause cancer. Hypoxia, the blocking of oxygen into cells, can be linked to the formation of cancer.

A common phenomenon and finding is inflammation. Chronic inflammation that leads to wounds that don’t heal. This is another provocative agent for the initiation of cancer. Rare germline mutations, such as the mutations in the BRCA1 gene that a lot of people hear about because of Angelina Jolie bringing attention to that area. Viruses, Hepatitis virus, papillomaviruses. And there’s a variety of viruses that can be linked to cancer. Age. The older people get, the greater the risk of cancer.

All these provocative agents all damage respiration. Their common link to the origin of cancer is damage to the mitochondria, and damage to the respiratory capacity of the cell. So the paradox is solved once people realize that these disparate, provocative agents work all through a common mechanism, which is basically damage to the cellular respiration.

Now, but people say, “Well what about all the genome mutations? What about all these mutations?” Which is a major focus in the field right now, is that cancer is a nuclear genetic disease. Now what happens is the integrity of the nucleus and the genetic stability of the nucleus becomes unstable once energy from respiration becomes defective.

Now it’s very interesting. All of the so-called provocative agents that are known to cause cancer through damage to respiration release these toxic reactive oxygen species, which then cause nuclear genetic mutations. And this is what most people are focusing on. The nuclear genetic mutations in the tumor cells are the targets and focal point of the majority of the cancer industry. Now, when you look at the disease as a mitochondrial metabolic disease, the nuclear genetic mutations arise as secondary downstream epiphenomena of damage to the respiration. So what most people are focusing on is the downstream effect, rather than the cause of the disease.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: You’re saying that because mitochondria are damaged and energy output is damaged, that causes the cell to lose it’s integrity?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Lose the genomic integrity.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ah, genomic integrity.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah. Most people you talk to about this, they say “Oh, cancer’s a genetic disease. We’re trying to talk all these genetic mutations. Every kind of tumor has all kinds of mutations. We need personalized therapies because the mutations are different in all the different cells, and the different types of cancer.” And that’s true, but all of that is a downstream effect of the damage to the respiration.

So, people are focusing on red-herrings. They’re not focusing on the core issue of the problem, which is stabilized energy metabolism. And this underlies the reason for why we’re making so little progress in managing the disease.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, I don’t know if you can break it down into a bit more detail. The mitochondria are made up of several parts: the outer membrane, the inner membrane, and so on. Is it certain parts, or is it any part of the mitochondria that’s getting damaged?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, it’s very interesting. It seems to be we’ve defined the lipid abnormalities, the lipid components of the inner membrane of the mitochondria. So there’s certain types of lipids that are enriched primarily in the inner membrane of the mitochondria. This lipid called cardiolipin. It’s an ancient lipid that’s present in bacteria and in mitochondria, but it plays a very important role in maintaining the integrity of the inner membrane, which is ultimately the origin of our respiratory energy, which is that inner membrane.

And many of the proteins that participate in the electron transport chain depend, or are dependent under interaction in the lipid environment in which they sit. So, lipids can be changed dramatically from the environment, which then alter the function of the proteins of the electron transport chain, effecting the ability of that organelle now to generate energy.

This is a real issue, and that inner membrane can be effected by all these carcinogens, radiation, hypoxia, viruses. The viruses themselves, or the products of the virus, will enter into the mitochondria and take up residence, thereby altering the energy efficiency of the infected cell.

And most of the cells die. When you interfere with respiration, most cells die. But in some cells of our body that have the capacity to up-regulate fermentation, these primitive energy pathways, they survive, and they go on to become the cells of the tumor.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, thank you for that. So, this is a very different theory to that which most people have come across, which, of course, you just outlined with the DNA mutations. Which bits of research have you pulled together in your book, and in your presentations, that you feel like present this view of the world the most strongly. Are there key research elements, researchers that have gone on, and maybe it comes down to four pieces that you feel strongly support this versus the other argument?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: I think that’s an extremely important point. What is the strongest evidence to support what I’ve just said? And what I did in my book in evaluating the therapeutic benefits that we’ve seen in managing cancer by targeting fermentation energy. How is it possible that we overlooked this information? It’s very interesting.

Over the last 50 years, various sporadic reports had been published in the literature showing that if the nucleus of the tumor cell is placed in a new cytoplasm, a cytoplasm that has normal mitochondria – and this is cytoplasm either from a newly fertilized egg, or an embryonic stem cell. Because now we have this technology where we can do these kinds of nuclear transplantations. And this ultimately was what lead to the cloning of Dolly the sheep, and these kinds of experiments. These had been done many, many years earlier in frogs, and in mice, before we moved on to the larger mammals and things like this.

But it became clear that when the nucleus of the tumor cell was placed into the normal cytoplasm, sometimes normal cells would form, and sometimes you could clone a frog, or a mouse, from the nucleus of the tumor cell. Now this was quite astonishing. Because people were thinking you would get cancer cells, because the mutations in the nucleus, if the hypothesis is correct that this is a nuclear genetic disease and the gene drivers are in the nucleus, then how is it possible that you could generate normal tissues without abnormal proliferation. In other words, normal, differentiated tissues from the nucleus of a tumor cell.

I was able to pull together a variety of these reports that had been sporadic in the literature over 50 years. And when these reports came out, it was considered kind of an oddball report that didn’t support the gene theory, but most people discounted it, because it was one singular report. But every four or five years, another report. Eight years would go by, another kind of report. And some of these studies were done by the leaders of the field, the key developmental biologists, the best there were. These people were heavy-weights in the field.

And they were coming to the same conclusions. That we were not getting tumors from transplanting the cancer nucleus into a normal cytoplasm. We were cloning mice, we were cloning frogs. We were seeing normal regulated cell grow. Now how can this happen, if the nucleus is supposed to be driving the disease?

So what I did was, I put all these reports together in a singular group. And I distilled it down to what the ultimate results showed. And then when you look at the whole group of papers, together for the first time, and the conclusions are consistent from one study to the other, using totally different organisms, totally different experimental systems, the results are all the same. The nuclear mutations are not driving the cancer disease.

And then if you take the normal nucleus and put it into a tumor cytoplasm, you either get tumor cells or dead cells. You never get normal cells. So this was clear. It became very clear to me, and when people look at these kinds of observations in their group and their totality, it’s a devastating statement on the nature of the disease. It’s not a nuclear genetic disease, it’s a mitochondrial metabolic disease. And the field has not yet come to grips with this new reality.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Just on that point, quickly, if you were to predict the future, do you think that this view of cancer metabolism is going to get traction in the near future? Say the next five years, next ten years, and what will it take to make that happen?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, it’s already gaining a lot of traction. People are now coming to realize that metabolism is a major aspect of cancer. But, unfortunately, what the field has done, there’s still links to the gene theory. So, the top papers come out and they say, “Oh, the abnormal metabolism in cancer cells is due to the nuclear gene mutations. Therefore, we still must be on the quest to find out what these mutations do.”

They have not evaluated in the depth of the information that I’ve presented. It becomes clear that this is not a nuclear genetic disease. So the mutations are not driving the disease, they’re the effects of the abnormal metabolism.

Now, there’s a groundswell of new interests in this. Now this opens up a totally different way to approach cancer. Once you realize it’s not a nuclear genetic disease, but it’s a mitochondrial metabolic disease, you have to then target those fuels that the tumor cell is using to stay alive. These amino acids and glucose, which can be fermented. Those molecules that can be fermented through these primitive pathways now become the focal point of stopping the disease.

So it becomes a much, much more manageable and approachable disease once you realize that if you take the fuel away from these tumor cells, they don’t survive. They become very indolent, they stop growing, they die. And now this gives you an opportunity to come in and target and destroy these cells, using more natural, non-toxic approaches.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. If you could reinforce that a little bit, because as I understand it, the current approach, which is pushed the most, is to target all of the different nuclear genetic mutations – and there’s many, many thousands of them, you can’t really count how many there are, because it’s constantly developing – versus, with mitochondria, as I understand it, mitochondria are all the same. So it’s a completely different problem when you look at it from that respective. Am I summarizing it correctly?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yes, I think you’re absolutely right. I mean, it’s a completely different problem. It now becomes a problem of energy metabolism. And the nucleus becomes a secondary peripheral issue.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. And the fact becomes much simpler, because you’re targeting the same problem versus thousands of different problems.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Absolutely.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And then therapy is… Today we’re developing thousands of hundreds of different drugs to target different types of cancer.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, it makes no sense. And the issue is every single cell in the tumor suffers from the same metabolic problem. But every single cell in the tumor has a totally different genetic entity. And we’re focusing on the very different aspects of every cell, rather than the common aspects of every cell.

The problem becomes a much more solvable problem once you target the commonality. The common defect expressed in all cells, rather than the defects that are expressed in only a few of the cells. You would not do that until you came to the realization, and saw the data, that this is a disease of energy metabolism, not nuclear genetic defects. It’s a totally different way of viewing the disease.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Thank you.

This may be kind of off subject for you, let me know if it is. But, I understand it, there’s also, more and more people are starting to link other types of diseases – say multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, and some of the other chronic diseases that we have and are not very solvable today – to mitochondrial disease. So I’m wondering if in any way you link that to the same origin of cancer, here. That we’re discussing.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, those diseases, that’s true. There are mitochondrial abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, and Type 2 diabetes. I mean, you can go right down the list and find a mitochondrial connection to a lot of these different diseases. But the mitochondria can be damaged, and insufficient, and influenced in many different kinds of ways. So, only cells that can up-regulate, significantly up-regulate fermentation, can go on to form tumor cells.

But many of our cells are not killed outright, and they struggle. For example, the brain. We rarely get tumors of the neurons in the brain, because if you damage the respiration of the neuron, the neuron will die.

Many of the tumors in the brain come from the glial cells. These are supportive cells of the brain, they play an extremely important role in the homeostasis of brain function. But those cells have a greater capacity to ferment than do the neurons. So when mitochondria are damaged in neurons, the neurons usually die. You can never get a tumor cell from a dead cell.

Now Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, these are situations where populations of neurons die from reactive oxygen species. So these reactive oxygen species, which are produced by inefficient mitochondria, kill the cell. And the cells never form tumors, they just die. So you have populations of cells in the Substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease, or in the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease, where the neurons are dying. And they’re dying from mitochondrial energy inefficiencies.

And the idea then, is can we enhance neuronal function by using therapies that will strengthen mitochondrial function. And the answer is, yes. And this is why these ketogenic diets are showing therapeutic benefit for a variety of different ailments, a very broad range of ailments. But the diets and these approaches – what we can therapeutic ketosis – can enhance mitochondrial function for some conditions, and can kill tumor cells in other conditions.

So one now has to appreciate a new approach to managing a variety of diseases that may have a linkage through inefficient mitochondrial metabolism.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Could you talk about – we’re coming into treatment here a little bit now, based on your theory. There’s the difference between ketone, or like, fat versus glucose metabolism in the mitochondria. And you were just talking about efficiencies. Could you go over that? What is the difference there? Why is it that glucose metabolism is different that of fats and the production of ketones?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, well the body is very flexible. It can burn energy from carbohydrates, which is glucose, or it can burn energy from fatty acids. Or it can burn energy from ketones. And we evolved as a species to survive for considerable periods of time without food. It’s amazing how people don’t understand this. They think if they don’t eat food in a week or less, they’re going to drop dead. This is nonsense.

We evolved as a species to function for long periods of time. As long as we have adequate fluids, water, the human body can sustain functionality for extended periods of time without eating. Now, you say to yourself, well where are we getting our energy. We evolved to store energy in the form of triglycerides, which are fat. And many of our organs store fats to various degree, and we have fat cells that store fat.

Now, when we stop eating, the fats are mobilized out of these storage vacuoles in the cells. And the fats go to the liver, and our liver breaks these fats down, like a wood chipper, to these small little ketone bodies, which now circulate through the bloodstream, and they can serve as an alternative fuel to glucose. So we can sustain, because the brain has a huge demand for glucose, but the human brain can transition to these fat breakdown products called ketone bodies.

So this all comes from storage fat, and our brains can get tremendous energy from these ketones. The energy in food comes from hydrogen carbon bonds that were produced during the production of the food. Ultimately from planets and the sunlight. But the energy in the bonds is ultimately derived from the energy of the sun. Now, our bodies break down these bonds, and recapture that energy. What we’re doing then is just recapturing this energy.

Now ketone bodies, when they’re burned in cells, they have a higher number of carbon oxygen bonds. They produce more intrinsic energy than does a glucose molecule, which is broken down to pyruvate, which is a glucose breakdown product. And when ketones are metabolized, they produce fewer of these reactive oxygen species. They work on the coenzyme Q couple within the mitochondria to produce clean energy, energy without breakdown products. It’s a very efficient form of energy.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I like that analogy there, because people could relate to how we had lead gas before, and we cleaned it up a bit, and now we’ve got less waste products in the environment.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah!

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s a little bit similar.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: It’s the same thing. I mean, our bodies are so super energy efficient when we begin to force them into a situation. In the past, this was done all the time, because in the past the humans almost were extinct a number of geological epochs, for the ice ages, lacks of food and all. And I mean, we have a very energy efficient machine in our bodies that can generate this energy from within. Clean, powerful, efficient energy that allows us to sustain our mental and physiological functions for extended periods of time.

And this comes from the genome. Our genome has a remembrance and a knowledge to do this. It evolved over millions of years to do this. The problem today is that this capability is suppressed by the large amounts of high energy foods that are in our environment. And what happens, this then creates inflammation and the kinds of conditions that allow inefficiencies, and eventually inflammation and the onset of cancer.

So, returning to the more primitive states allows our bodies to reheal themselves. And, as I said, here’s the issue. The nuclear genetic mutations that collect in these cancer cells prevent those cells from making the adaptations to these food restrictive conditions. So, because the mutations are there, the cells are no longer flexible. They can’t move from one energy state to the other, like the normal cells can, which have integrated genomes.

So, the mutations can be used to kill these tumor cells, but by forcing the body into these different energy states in a non-toxic way. It’s not necessary to have to poison people, nuke people, surgically mutilate people to make them healthy. There’s natural ways we can do this, if we understand the differences in metabolism between normal cells and cancer cells.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, from your perspective, anything that would help to repair mitochondria, would that be helpful against cancer?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. You’re not going to get cancer in cells that have very healthy mitochondria. If mitochondrial damage is the origin of cancer, and the cells have very high efficient mitochondria, it’s very unlikely. The risk of developing cancer in those situations is remarkably low.

There are groups of people that we have in the United States, the Calorie Restriction Society of America. It exists in other areas throughout the world. These people have a very low incidence of cancer. They’re in a constant state of ketosis, and the incidence of cancer in these people is very, very low.

Now, I have to admit. This is not an easy lifestyle. People don’t want to be restricting themselves all the time, and doing this stuff. This is the issue. We live in an industrialized society that has come a long way to create an environment that is free of the massive kinds of starvations, and these things that existed in the past. So it’s hard to take your body and go back into these primitive states to do this kind of thing.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So, there’s [unclear 31:58] a really big focus on what you’ve been saying on reactive oxygen species, which is kind of like the mini explosion that takes place inside a car when it’s running. And I think people can relate to the fact that all engines are causing damage while they’re running, because they’re producing heat, and so on.

So, with the mitochondria, it’s basically the same. And you’re saying that when we’re on a ketogenic diet, or where we’re fasting and we’re producing this more efficient type of fuel, it reduces our assets [unclear 32:23] causing less damage. And it’s an important type of the damage that is caused to mitochondria.

And this is why eventually it helps with the status of the mitochondria, to heal them and repair them, or to limit the additional damage that goes on which would help to promote the cancer. Is that a good summary, or have I got some things wrong?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: It’s a very close analogy. I would say this is exactly what it is. We damage our body by the kinds of foods we eat, the kinds of environments we’re exposed to. And the mitochondria in certain cells just get damaged, and these cells then revert back to a more primitive form of energy, which is fermentation, which then leads to a total dysregulation of the growth of the cell. Collects these mutations that come as a secondary downstream epiphenomena of this.

And the thing of it is is, how do you target and eliminate those kinds of cells. And cancer, people must realize, this is systemic disease, rather than a focal disease. People say, “Oh, what does he study? He’s a liver cancer, breast cancer.”

These cancers are all the same. They’re metabolically all the same. You need to treat cancer in a singular global systemic way, and this then will marginalize and reduce the growth of these cells. And you have to be able to do it non-toxically.

And these ketogenic diets, or therapeutic ketosis, is just one way to enhance the overall health and well-being of the body while targeting and eliminating these inefficient cells. And this can be done if people do it the right away.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great. Thank you very much.

So, based on this theory, what kind of biomarkers would give us insights into someone’s potential to develop cancer? Because today we look at 23andMe data, for example, genetics to kind of asses our risks of future cancer. For instance, on mine it says my highest potential cancer is lung cancer. And that’s pretty much the only markers that we’re given. Are there markers related to mitochondrial function, or damage, that you would feel that would be relevant to estimating a future potential risk of cancer?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, well I think one of the risks of cancer is high blood sugar, blood glucose levels. I mean this creates systemic inflammation, which underlies a lot of the so-called chronic diseases that we have, including heart disease, and Type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer. These are just the predominant number of chronic diseases that we’re confronted with.

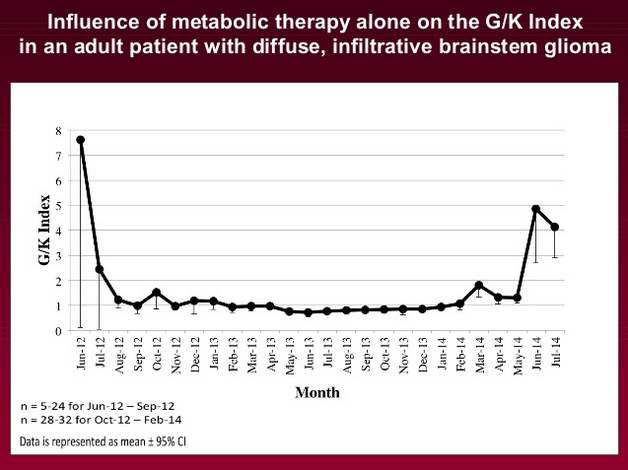

So, if we know that high blood sugar is a provocative agent that increases the risk for cancer, then making sure your blood sugar levels are low. And the other thing too is elevation of ketones. So we developed what they call a glucose-keton index that can be used for people to prevent cancer, as well as managing the disease.

So if the glucose-ketone index, which we have defined as the ratio between the concentration of glucose in the blood to the concentration of ketone bodies in the blood. If this index can be maintained as close to 1.0 or below, the body is in a very high state of therapeutic energy efficiency. Which is then going to reduce the risk for all of these different kinds of chronic diseases. So, and if you look at most people with chronic disease, their index is about 50 or 100, rather than 1 or below 1.

We’ve just developed this, and we’re working on a paper. It’s called the Glucose-Ketone Index. It was designed basically for managing cancer, because patients who have cancer, if they want to know what these therapies are doing, how they’re working, you look at your index.

Now, people who don’t have cancer, who would like to do something to reduce their risk, they would do the same thing. And people would say, “What’s your index today?” “My index is 1.2.” You’re in a very good state of health.

And if most people – I can guarantee – people who eat regular foods, their indexes are about 60 or 70, not 1.2 below. Because what you do is when you have a lot of carbohydrate in your bloodstream, the ketones are very, very low. They’re like 0.2, 0.1. And you’re blood sugar is like 4 or 5 millimolar, and your blood ketones are 0.1 millimolar. Well what do you think your index is going to be? It’s going to be huge.

But then if you increase your ketones, if you can bring the ketones bodies up to the same level as glucose, then I have a 1.0.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Is this sensitive enough to manage potential? You made a very clear scenario of 60, where that’s a very dangerous situation to be in.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Oh no, no. I don’t want to say it’s dangerous. I want to say it’s the norm.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Oh, okay. Great.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: It’s not dangerous. When you take somebody who has Type 2 diabetes, and his blood sugar is like 300 milligrams per deciliter – and you have to divide that by the number 18 to bring it down to millimolar – and his ketones, you can’t even measure them. I mean, these guys are inflamed. Their bodies are in an inflamed state. And inflammation will cause all kinds of effects.

So, you want to bring people down. How do you get these low numbers? Well, you can either go on these calorie restrictive ketogenic diets, or you can do therapeutic fasting, which is water only fasting, for several days. You’ll bring those numbers right down. You’ll get into an extremely healthy state. Because the ketones go up naturally when you don’t eat, and blood sugar goes down naturally when you don’t eat.

So then you enter into these states, it’s called therapeutic ketosis. The problem is it’s very, very difficult for most people in our society to do this, because our brains are addicted to glucose. If you take somebody who stopped eating for 24, 36 hours, this guy thinks he’s going to go crazy. It’s almost like trying to break the addictions to cigarettes, alcohol, drugs. It’s not easy. It’s very, very difficult to break the glucose addiction.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely. It takes a little bit of time to change your metabolism.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So we spoke to Jimmy Moore before. I don’t know if you connected with him before, and his book…

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, I know Jimmy.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, right. So we spoke about some of the different ways to measure ketones. We had the blood test, the blood-prick test with the precision, which is a little bit expensive today. And you have the breath test, the Ketonics, which has just come out. With that index, are you using the blood-prick test, or are you using maybe blood labs, or something a bit more complicated?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: There’s a couple of companies that use the blood test, the most accurate. It’s more accurate than the breath, blowing into a ketosis meter. Or you do urine sticks. So the most important measure, of course, is blood. So you have to take a blood stick. There’s only a few meters that can do both ketones and glucose, using the same meter.

You have to use different sticks. There’s a ketone stick, and a glucose stick. So from the same drop of blood, you can get your blood sugar, and then you can put a new stick into the machine, which is a ketone stick, and then you can take the same drop of blood and get your ketones.

Now what we did was we developed a calculator so that all the person would have to do is to push the button on the meter, and it would calculate already your glucose-ketone index. This would give you a singular number from a drop of blood.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you’ve developed your own device, you’re saying, which does that calculation?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: We developed the calculation. It’s called the Ketone Index Calculator. And because you have to convert everything back to millimolar. Because many of the ketone meters give you blood sugar in milligrams per deciliter, and ketones in millimolar. So we have to convert. You can do all this by hand, you just have to do the divisions and all of this stuff.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you’ve got an online calculator where people can put their values in and it will give them the index?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, we don’t have that yet. What we did was develop the calculator that could be incorporated into these meters.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I see.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: This is the thing. So people, regardless of whether you’re a cancer patient and you want to manage your disease, or you’re a person who wants to prevent cancer, or you’re an athlete who wants to know what his physiological status is, or you’re someone who wants to lose weight. All of these issues, you can get a sense, a good solid biomarker sense, by looking at your glucose-ketone index.

And everybody can do that from these meters that are capable. But the meters right now are not designed to give you glucose-ketone indexes. And this is what we’re saying; it’s the index that will tell you your overall status, your health status.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So I imagine, right now, you’re approaching the providers of these tools to see if they can incorporate this calculation into their devices?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yes. Exactly. They don’t have it yet. They’re not even aware yet of the potential market, or interests, among the general population. Not only for people that are afflicted with various diseases, but people who are healthy and don’t want to get those diseases.

So this is a very simple tool. The only drawback from it is you have to stick your finger with a little prick to get a little bit of a drop of blood. The people with Type 1 diabetes do this regularly. This is not an issue. But for those people who are into this, and they want to do it the right way, and they want to get accurate biomarker measurements, then they would do this. For those people who are interested in this.

This is invasive in the sense that you have to prick your finger to get a drop of blood, but it’s not invasive in the sense that you have to take tissue samples, or any of this kind of thing.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And so this is something that people could do on an on-going basis? So I’m guessing for someone with cancer – I don’t know if this would be something you would say – they’d probably want to look at daily, or every few days, or something like that. And someone else, maybe it’s just something they need to do a lot less intensive routine, in terms to just monitor the levels of their general ketogenesis.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yes. You’re absolutely right about this. People who are trying to manage their diseases thoroughly might want to do this maybe once or twice a day. Just like someone who might have Type 1 diabetes. They measure their blood sugar several times a day.

The issue right now is the glucose strips are relatively cheap – they’re like 50 cents a piece – but the ketone strips are much more expensive. They can range from anywhere from $2 to $5 a stick.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Do you know if that’s due to economies of scale? Or if it’s simply because not enough people are using them yet?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yes, it’s an economy of scale, absolutely. Because very few people measure their ketone levels. But now, linking those ketones to your overall general health, a lot of people would be interested in this.

And people in general like numbers. They want to know, and especially a singular number that would dictate your state of health. If you can say to somebody, “Listen. My index is between 1.1 and 0.9,” people would automatically know this guy is in a tremendous state of health.

People like to know that. You say, “Where is your number?” And people like to keep log books. They like to record these numbers. And they also link this to a greater sense of well-being. People who have their numbers down in these ranges, they tell me – and I’ve done it. Some people get into a state of euphoria. It’s like unbelievable.

When your body starts burning these ketones, it’s like you enter a new physiological state. And athletes are doing this sometimes. So it’s a whole new realm of how to monitor your own health with accurate biomarkers that give you an indication of your health status.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So do you follow a similar prescription to Jimmy Moore? I believe you understand his approach, where he’s eating a high fat diet, or sometimes he’s fasting. Kind of like intermittent fasting, which has become pretty popular these days.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well intermittent fasting is, from what we’ve seen in our work, you don’t get the health benefits, the power of the health benefit, until you’ve gone three to four days without any food. Just drinking water. And then those who can go a week, like a seven day period, this is really when you start to see your blood sugars going down and your ketones going up.

But once you can get into this zone – we call it the zone of therapeutic management – where now you know your in the zone, this is where the health really comes in. And when you say periodic fasting, now there’s a lot of people that I know – numbers of people – who have a rather restrictive diet for the week, and then one day a week they’ll not eat anything. So, it’s one day off on food, like a 24 hour period where they’ll just have maybe a green tea, no calories, or just pure water.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Some of the intermittent fasting regimes propose that approach, a 24 hour fast every two days.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, but then you’ve got to know, okay what did that do to my index? How effective was the 24 hour fast on my index? And you look down, you say, “Well, I didn’t get my ketones up very far. They went from 0.1 to say, 0.5.” Okay, but if I go four or five days, it goes from 0.1 to 3.0. Oh wow, this is the magnitude difference.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So have you looked at different people, because when we were talking to Jimmy, he was saying that different people have different responses. It’s based on their current state of metabolism. They’ll have to be more extreme in their approach to get the same level of ketones, and the same impact on an index, depending on, potentially, how damaged their mitochondria are. I don’t know how you look at it.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, no, that’s a really important point. It’s certain people. It’s also certain sexes. Women can get into these ketone states much easier than men. And young people can get into these zones much, much easier than can older people.

So it’s an age issue, it’s a gender issue. We’ve seen some of our students get down their blood sugars down into the low 30s, which people would say would be a crisis situation, you’d have to go to the hospital. But their ketones are elevated, and when the ketones are elevated, you have no crisis situation. It’s only when you lower blood sugar and don’t elevate ketones that you have this situation.

Males have a lot more muscle, they tend to burn protein, which can be converted to glucose. So their blood glucose doesn’t go down as sharply as women, the blood glucose of females goes down. Females can get their blood sugars down and their ketones elevated – from all the data that we’ve seen for several years on different gender – and this is what we see.

And older people are simply locked into a much longer lifestyle of high glucose. And for them to get their blood sugar down, it’s a real struggle. And also their muscle mass over the age. They have a lot of other issues that play into this whole thing.

And you’re absolutely right, it’s an individual thing. Some people can’t tolerate this. They get really sick, they get light-headed. Where other people make the adaptations much more quickly. So again, people have to know their own physiology.

But they have to have the biomarkers that let them know. They need to see these numbers, and once they see these numbers they’ll know that they’re on the right path, and they probably can do this if they persist a little bit longer. Rather than throwing their hands up, not knowing what’s going on, being very frustrated. And as I said, once you have this information and knowledge, that these kinds of things become much easier.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. It definitely helps with your confidence in something if you can see that, maybe you don’t feel better, or you don’t feel a difference yet, but if you see the numbers starting to move then it gives you that sense of accountability, and motivation also. I think that’s one of the very helpful aspects of these kind of indexes that you’re talking about.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Absolutely. This is a very important point, you’re absolutely right about this. Because when you see that you’re killing yourself, and nothing’s happening, or you don’t feel anything, but when you see numbers starting to change in the direction you know your hard work is starting to pay off. And then you get motivated, and you want to see then how far you can push these numbers.

Now this is not going to hurt anybody. You’re just lowering blood sugar and elevating ketones, and your body gets into a new state of health. And people feel it, believe me. You can feel this stuff happening. But there’s a rocky road going from the high glucose state to the high ketone state. And that rocky road can be more rocky for some than others.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely. So there are other aspects to mitochondrial health that certain people are looking at at the moment. I don’t know if you’ve come across any of these, but I thought I’d just throw them out in case you had some comments on them.

Some people are talking about mitochondrial repair, in terms of repairing the membranes with specific lipids, by providing those lipids to help reinforce the mitochondria. Other people talk about things like PQQ to help stimulate biogenesis of new mitochondria. I don’t know if you’ve heard about these things, or have any ideas or opinions on them.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, in my book I called it autolytic cannibalism. And this is basically, the mitochondria can either be rescued, enhanced, or consumed through an autophagy mechanism. And when you stop eating, now every cell in the body must operate at its maximal energy efficiency. That means that the mitochondria in those cells must be operational at their highest level of energetic efficiency. Otherwise the cell will die, and the molecules of that cell will be consumed, and redistributed to the rest of the body.

Now, in cells that have some mitochondria effective, or more efficient than other mitochondria within the same cell, the inefficient mitochondria can be incorporated into the lysosome. The parts of that mitochondria can then be redistributed to the healthy mitochondria within the cell. And this way you eliminate internal energy inefficiencies, but without having to kill the cell, because the cell is able to repair itself.

Whereas those cells that can’t repair themselves die, and their molecules are then consumed by macrophages, excreted back into the blood stream, and the nutrients now are used to support the health and vitality of those cells in the body that have this higher energy efficiency. It’s a remarkable state of efficiency. So it works both with individual cells, and throughout the whole entire physiological system.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great. Thank you. I’m just thinking, you’ve spoken about fermentation versus respiration. Is there any way to measure that, that you know of? Is that being done in studies? So are the studies coming out are comparing the state of fermentation versus respiration taking place in people’s bodies, and correlating that to cancers, or anything like that?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, that’s kind of hard to do, because we all have lactate in our bloodstream, and the lactate comes from erythrocytes, our blood cells. The blood cells have a shorter half-life than many of the other cells in our body, and those cells have no mitochondria. They have no nucleus. So they’re little cytoplasms that primarily ferment.

But they don’t use a lot of energy, because the role of that cell is simply to exchange gases. So it floats around in our tissues, it deposits it’s oxygen and picks up CO2, as more or less a little mailman running around, picking up this and dropping that off. And they have a shorter half-life. But they have lactate.

Now if you have a tumor, or if you’re under hypoxic stress, lactic acid will go up in your bloodstream. But it’s hard to know if a tumor will do that. Sometimes what tumors will do, they have a phenomena called cachexia. This is where the tumor cells will send out molecules that will digest proteins, or dissolve proteins in our muscles and other proteins. And these proteins then go to the liver, and are broken down into amino acids, and the amino acids are conjugated into glucose.

So the glucose goes now into the tumor cell, and some of the proteins and the amino acids go to the tumor cell after being broken down. So the tumor is essentially causing our body to starve to death. We might be eating, but it looks like we’re not gaining any weight, and we’re becoming moribund and looking like we’re starving to death. This is an effect of the tumor,.

Sometimes you don’t see that. Sometimes lactic acid will go up, and sometimes it won’t. So there’s a lot of ambiguity of looking at a good biomarker to assess the state of what level of tumor growth you might have, other than the fact that you’re losing weight even though you’re eating. Which is the cachexic state; you’re kind of wasting from within. This is the whole thing.

And this is one of the fears that the medical profession has with cancer patients, because they say these poor people are losing weight through this cachexic mechanism, and then you come along with a metabolic therapy, and they say, “Oh, this can’t work.” But the issue, of course, is that there’s two types of weight loss. One is a pathological weight loss, and the other is therapeutic weight loss.

Pathological weight loss is cachexia, and of course if you treat it with toxic chemicals and radiation, you get so sick with fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting. I mean, this is pathological weight loss. Therapeutic weight loss is you’re losing weight, but your body is getting extremely healthy, and killing cancer cells at the same time.

So weight loss can come in two different varieties: pathological and therapeutic. And people have a tremendous difficulty in understanding the differences between these kinds of weight loss.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I think we’ve mentioned on a podcast before that when people are fasting in this state, they actually feel better, even if they have, for instance, chemotherapy. They tend to do better in chemotherapy when they have been fasting.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yes, because it reduces inflammation. We published a number of papers showing how therapeutic fasting reduces systemic inflammation. Systemic inflammation contributes to a pathological state, and facilitates tumor growth.

So therapeutic fasting, while at the same time you’re taking a toxic drug, it’s like what are you doing here. But it does take the sting out of that toxic drug. People feel better when they’re therapeutically fasting. I think Longo’s group down at University of Southern California has clearly shown that some of these cancer patients can do a lot better, and feel better, when they’re fasting while they’re taking chemotherapy.

But you’re absolutely right about that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thank you so much for this interview[unclear 53:08] Thomas. I want to ask you just a few more questions to round off now.

What do you think will happen in the next five or 10 years, or hope? What are your visions for this area, in terms of biomarkers, like testing devices, or change in the way we approach this? Do you think there’s specific opportunities ahead, are there specific questions you’re looking at at the moment to resolve, in research, or so on?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, well I think the people themselves are demanding a change. The issue is that they haven’t been shown other alternatives, other than the standards of care, which are conducted by the major medical schools: Dana Farber Cancer Center, MD Anderson, John Hopkins, Yale Cancer Centers, Sloan Kettering, UCSF. The major industries of cancer and academics are closely aligned in how to do this.

And it’s not working. We’re having about 1,600 people a day are dying from cancer in this country. And the statistics in other countries in Europe, and China, and Japan, are not far off of this. And if we had Ebola outbreak in this country, where 1,600 people were dying a day, this would be of the greatest catastrophe that people can imagine.

But for cancer, it seems to be okay. This is the norm. Well it doesn’t have to be this way. It doesn’t have to be this way. And the issue here is that the people see that we have more, and more survivors, and people doing pretty well on these metabolic therapies. Why are we not doing this as more of a general treatment as opposed to these toxic approaches to manage the disease?

So I think the change will come from the grassroots. I don’t see it coming from the top medical schools, because these people are not trained. They’re medical education doesn’t give them the training to identify these approaches to therapy. It’s not part of the medical training.

There are a number of physicians that are recognizing this now, and they want to become part of this new approach to cancer management. Now, you have to realize that we’re just beginning. This is just a new field, it’s a beginning field. Even though the science is well, well established, the implementation of this science for patient health is just at the beginning. It can be refined, it can be modified.

A lot of this now we’re talking about, the potential for managing cancer in a non-toxic way with greater therapeutic efficacy, is just beginning. So, I think that we need more trained people. We have to have people that understand this. Eventually, these kinds of approaches will be more and more recognized, and more and more implemented in the overall society.

The problem is people have not yet found a way to make a large profit on this kind of an approach as you can with certain drugs, and immunotherapies, and these kinds of things. But that will probably come in time, once people understand what the best approaches and techniques are.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Another aspect I wanted is there’s more research being undertaken on mitochondria over time. Do you think that will help, in any way?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, I think it will help a lot, like you said, with the lipids. And we’re looking into this ourselves. I think there’s ways that we can enhance mitochondrial energy efficiency through various diets and supplements, and things like this.

And there will be a real quantitative measures that can assess this, for people to recognize what works and what doesn’t. So I think it’s just that it’s an area that has been not well appreciated, and not well recognized.

And as long as people think that cancer is a nuclear genetic disease, the focus on the mitochondria hasn’t been there. People have known the importance of mitochondria, and it’s been a very major area of scientific research. But it’s not recognized as the solution to the problem. It’s kind of a side effect.

What we’re looking at is understanding mitochondrial functions, and it’s interaction with the nucleus and other parts of the cell to maintain a healthy cell – a healthy society of cells – and a healthy overall physiology. All linked to the mitochondrial energy metabolism. This is going to be a very exciting new development.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, I agree. There’s not a day that goes past that I don’t think about mitochondria these days. And hear someone talk about it. It happens a lot on this show, also.

If someone wants to learn more about your work, and this theory of cancer, and the index you were talking about, where should they go?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, I wrote the book On Cancer as a Metabolic Disease: On the Origin, Management, and Prevention of the Disease. That’s published by John Wiley Press. Unfortunately, it’s a science book and it’s not cheap, like you’d find most of the Amazon books, but it gives you the literature, it gives you the science. It gives you the hard evidence to support everything that I’ve said.

Another book that’s just appeared is Tripping Over the Truth: The Metabolic Theory of Cancer, by Travis Christofferson, who’s written a book for the layperson, where he actually read my book and went back to test all the things that I was saying, and actually talking and visiting and interviewing those scientists who work in the gene theory, and work in the metabolic theory, and get the word directly from them. It reads like a novel, and it’s much less scientifically intimidating than what I wrote.

I wrote this book to convince my peers, and people in the cancer and scientific field, the evidence that supports what I’m saying. This sometimes can be intimidating to the layperson. Whereas Travis went out and actually interviewed those scientists, and asked them the specific questions. And now it becomes a very intriguing story; I mean, how did this cancer thing get so far out of whack with what we know about it. People like to see this, and read it.

So that is another book that’s generating… If you go on Amazon, you’ll see the reviews. They’re all quite outstanding for Travis’ book. And I’ve been privy to a number of other books that will be coming out over the next year, which are harping on the same general theme, that cancer is a metabolic disease, and it can be beaten by metabolic solutions. Totally different than what’s been going on in the main focus.

And this is kind of shocking, because you go to the top cancer centers, and they don’t speak anything about this. They’re still talking about the standards of care as they have been done, or they’re talking about immunotherapies, which is the new buzzword for the cancer field, where you’re going to identify all the mutations, and then make anti-bodies to the defective proteins, and then treat people. And they show a few survivors on the cover of the Wall Street Journal saying how wonderful this works. But they don’t show you the other evidence showing how many people are dying from this.

All this will change, because the people in this society, the public, is going to be fed up with the lack of progress, and what we have is a new way to approach this problem based on solid scientific fact. It’s just that these facts are not well understood or recognized at this point.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. Thank you very much, and we’ll put all of this in the show notes, so people will find these links easy. Also the index you spoke about, I’m guessing there’s nothing really published about that. If people go to your website in the future, will you have something on there which will talk about that in more detail?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah. We have a paper that’s under review right now, where we’ve submitted a paper for the index, and we’re in the process of making some revisions on the index. And the index was, in this paper, was mostly focused on managing brain cancer, but we also noted that this index could have a broad applicability to a whole range of different diseases.

And in the Journal of Lipid Research, which is the top journal in the field of lipid biochemistry, I edited one of the issues that was entitled Ketone Strong: Emerging Evidence for the Role of Ketones and Calorie Restriction for the Management of a Broad Range of Diseases. So, more and more scientists are getting involved in this, and more and more information will be coming out. Both in the professional scientific journals as well as in the public interests articles in journals, and magazines, and radio shows.

More and more people will be coming to know this, and I think the field is going to have to deal with it. And I think in the long run, we’ll emerge into a new way to manage these chronic diseases with a lot less toxicity, and greater efficacy.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great, great. Thank you. Now, just two more questions, personal questions for you.

What data metrics do you track for your own body on a routine basis, if any?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Well, basically I try to get on a scale and see how much I weigh. Obviously, if you can keep your body weight at a stable level for a period of time, this is certainly one way to maintain homeostasis.

I’ve done the three day fast, but as I said, when you’re older like myself, it’s very uncomfortable, but it’s certainly doable. It’s like training exercise. You’d have to do it probably a couple of times a year to get into the state. I think every time you do this, you become more confident in your ability to do it again.

There is a state of uncertainty and discomfort, like, “Oh my god, I’m not eating any food. How can I go, and I feel uncomfortable, and a little light-headed.” And you try to drink water to say, “Maybe I can fill my stomach up with water and I won’t feel as hungry.” And then you start getting water intoxication. And eventually you realize that you really don’t need to drink a lot of water, and you just have to bite the bullet.

But as I said, as we begin to do this, we realize that it’s not so life-threatening as everybody would think it would be. So I think I try to do that. But as I said to a lot of people, they said, “Oh, you must do this all the time.” No, I don’t do it all the time. But if I had cancer, I’d know exactly what I would do.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: What would you do? Just to speak it out clearly.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: I would stop eating.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Completely?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: I’d get my index down below 1, that’s for sure. And then I would transition off to these high-fat, nutritious kinds of diets, ketogenic diets, and maintain my index. And then of course, we’re investigating – it’s very hard to get funds to do this kind of stuff too, because it’s not considered sexy science – what is the best combinatorial therapy that would work with therapeutic fasting and ketogenic diets, that would put the greatest amount of pressure.

And most of it has to do with what kind of non-toxic drugs would you dovetail in with therapeutic fasting and ketogenic diets? And like hypobaric oxygen therapy, 2-deoxyglucose, 3-bromopyruvate, oxaloacetate. I mean, we can go down these lists. Most of these are non-patentable drugs, but they have tremendous power when used together with these other therapies. And most of this stuff is just trying to figure out the dosages, the timing.

These kinds of issues, it’s just like perfecting the engine. How did the car engine become so efficient today from the way it was in 1900?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So the things you just mentioned either stress the cancer cells specifically, like hypobaric oxygen, or they support the mitochondria, oxaloacetate, right?

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yes! Exactly. What you’re doing is you’re enhancing mitochondrial function in normal cells, and you’re putting maximal metabolic stress on the tumor cells. For the first time, we’re using our normal cells to directly combat and battle the cancer cells, while enhancing their health and efficiency.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So for someone who has, say we do a 23andMe test – like a lot of people on this podcast do their 23andMe test – and it comes out with some DNA, and it says, maybe you have a pretty high chance of cancer in your lifetime – and it could be lung cancer or whatever. Lung cancer’s not a good one, because often it’s smoking. So, one of the other more general ones, like breast cancer.

What would you basically say that they should be fasting once per month for three days, or twice per year for seven days, and maybe looking at those therapies you just outlined.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah. People who have Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which is an inherited germline mutation in the gene for P53 which encodes a protein in the electron transport train, or BRCA1. Product of the BRCA1 gene has been found in mitochondria. We look at a number of these so-called inherited genes that increase your risk for cancer. But as I told you, everything passes through the mitochondria The mitochondria are the origin of the disease.

So, the inherited mutations simply make that organelle slightly less efficient in certain cells of our body. Not all cells, but only certain cells, like the breast, the uterine, or these kinds of things. And we know that there are people, like if you inherit the BRCA1 mutation, your risk of cancer goes up significantly. But not everybody who has BRCA1 mutation develops cancer.

So clearly the environment can play a huge role in determining whether that gene will be expressed or not. You can do prophylactic removal of organs, and things like this, to reduce your risk. But it would be just as effective in my mind to transition the body to a metabolic state that would minimize the problem of that gene influencing the mitochondrial function. It seems a lot less draconian than doing these massive surgical mutilations.

Or you can do both. The idea is some of these inherited mutations, they might have a preferred organ – like a breast, or a uterus, or ovary – but you’re not going to remove all your organs. You’re not going to remove brain. You’re at a higher risk, so what can you do to lower your risk? As I said, if you keep your mitochondria healthy, the risk is going to be significantly reduced.

People need to know this so they can make choices that would be best suitable for them.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thank you so much for the information today. This is really an information packed episode. It’s got this great new take on cancer, which I think is very positive, because it’s talking about something which people can have more control about. So it’s not just that this is a new approach, and the older approach has been struggling for quite a while, it’s become very expensive, and so on, with not so much success, but also that this is an approach which is within people’s own manners, sphere of management.

A lot easier to start having an impact on their own lives. So it’s very positive from that perspective also.

[Dr. Thomas Seyfried]: Yeah, I agree. Absolutely.