In this episode, we explore how carbohydrate intolerance works. We look at the evolutionary template (basically the Paleo template), neuroregulation of appetite, carbohydrate tolerance, insulin resistance and sensitivity, and the factors that drive all of these.

– Robb Wolf

Robb Wolf (@RobbWolf) is basically the man responsible for bringing Paleo to the mainstream, in part via his New York Times Bestseller, The Paleo Solution. He also has a new book out, Wired to Eat, which covers many of the topics discussed in this episode.

Robb is a former researcher biochemist and review editor for the Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, and the Journal of Evolutionary Health. He is a consultant for the Naval Special Warfare Resilience Program and has provided seminars in Nutrition and Strength to organizations such as NASA, the Canadian Light Infantry, and the United States Marine Corps.

One of the takeaways from Robb’s new book, Wired to Eat, is using a 7-Day Carb Test. That’s testing a different type of carb seven days in one week to see what these do to you, and what your personal tolerance is to different carbs, because not every one of them affects you the same way, or like it would any other person.

I ran that test myself and the results are further down this page. This gives you a concrete example of what Robb is talking about when he talks about the 7 Day Test, how to measure blood glucose and how to understand how these carbs are affecting you differently.

The episode highlights, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

What You’ll Learn

- Damien extends his gratitude to Robb for getting him back to eating meat in the year 2010, which greatly improved Damien’s health (03:45).

- Robb’s book Wired to Eat approaches health from an evolutionary neuroregulation of appetite as starting point and progresses with dieting self-experiments (04:01).

- The insulin resistance theory and how the 7 Day Carb Test is useful in coming up with personalized diet plans aimed at improving health (10:46).

- The potential for low-carb / paleo diet and intermittent fasting to improve carbohydrate tolerance (18:50).

- Robb’s plans for experimenting with donating blood to reduce potential iron overload inflammation (19:58).

- The value of lipoprotein insulin resistance (LPIR) panel in determining ‘hidden’ insulin resistance, otherwise not detected by fasting glucose levels alone (21:05).

- Anthropometric measures, such as the waist to hip ratio, are only somewhat reliable markers of insulin resistance (24:28).

- Making use of the 7 Day Carb Test to track the process of recovering carb tolerance over time (24:53).

- Why sleep is the most important health parameter and how HRV is useful for tracking sleep quality and overall health (29:39).

- Integrating physical exercise into a busy life and optimizing exercise intensity (36:41).

- The ketogenic diet offers numerous therapeutic and health maintaining benefits (41:35).

- The role of the circadian rhythm in tuning meal consumption with the body’ demands throughout the day (45:35).

- People to follow & material for learning more about this episode’s topics (51:39).

- The best ways to connect with Robb Wolf and learn more about his work (53:14).

- The biomarkers Robb Wolf tracks on a routine basis to monitor and improve his health, longevity, and performance (53:45).

- The labs using NMR spectra technology to detect LPIR components with high precision (57:58).

- Robb’s one biggest recommendation on using body data to improve your health, longevity, and performance (58:28).

Thank Robb Wolf on Twitter for this interview.

Click Here to let him know you enjoyed the show!

Robb Wolf

- Main Website: Short life & career summaries of Robb Wolf and his team.

- Paleo Diet: An introduction on the Paleo Diet written by Robb.

- Robb’s Instagram: Where he spends most of his social media time and answers almost all posed questions.

- The Paleo Solution Podcast: Robb’s long running podcast exploring every area of evolutionary and paleo based lifestyles as well as many of today’s chronic health challenges.

Recommended Self-Experiments

7-Day Carb Test

- Tool/ Tactic: This test is described in detail in Robb’s Wired to Eat book and on his blog here. It consists of consuming 50g of carbohydrate from different carbohydrate sources (e.g. rice, lentils etc.) each day for one week.The goal is to identify which carbohydrate sources have the biggest impact on blood glucose levels, and thereby identifying which ones you are least carbohydrate tolerant for.In creating this test, Robb was inspired by the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Personalized Nutrition Project. We discussed personalized nutrition and interviewed the lead researcher, Eran Segal, from this project in Episode 48.The test entails preparing 50g of effective carbs, or another carb source, and eating only one type of this meal first thing in the morning (with the exception of coffee and water).

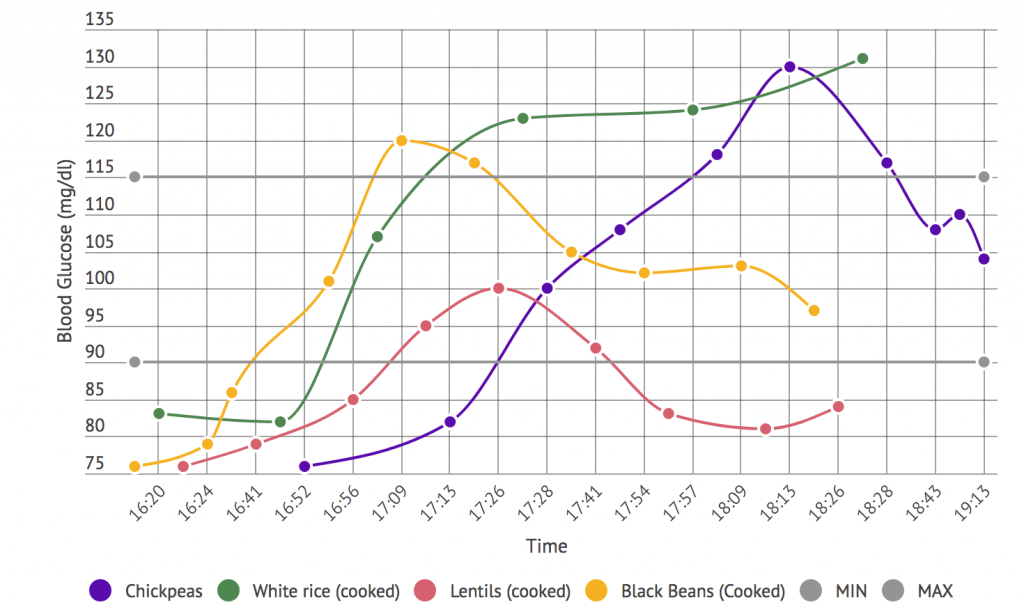

- Tracking: Track the food types, your blood glucose level before you consume the food and the time at which you eat. Exactly two hours later, test and record your blood glucose reading again.Is your blood glucose at the 2 hour mark over 115mg/dl? This can indicate carbohydrate intolerance with respect to that specific food.By understanding the carbohydrates you are personally intolerant of you can reduce your blood glucose variability significantly by just removing these from your diet (while still enjoying other carbs that your body is tolerant of).

Robb recommends that the 7-Day Carb Test is repeated approximately every 3 months, such that the time intervals are close enough to track improvements in particular carb foods insulin sensitivity, as well as tracking the body’s overall insulin sensitivity.

Damien’s 7-Day Carb Test Results

Before recording the interview with Robb I followed his carbohydrate testing protocol for some of the carbohydrates that appeal to me more.

I made a couple of modifications of the protocol to fit my profile better.

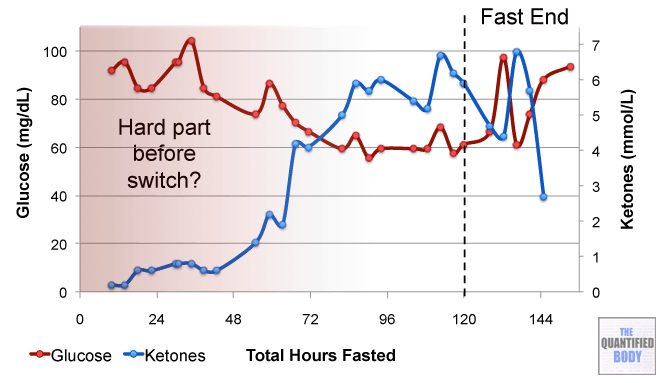

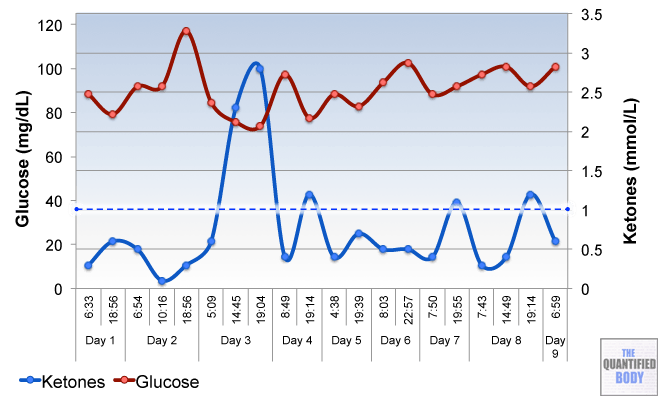

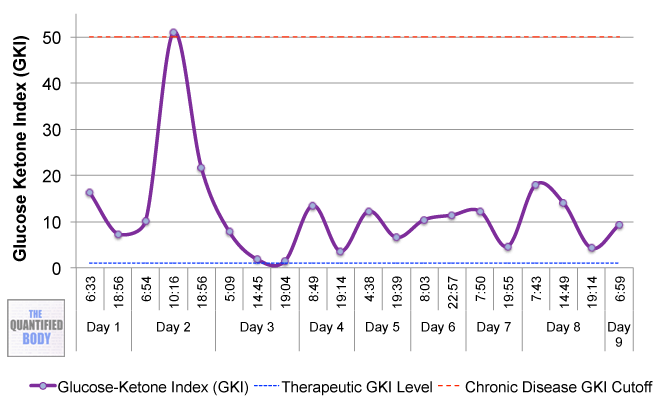

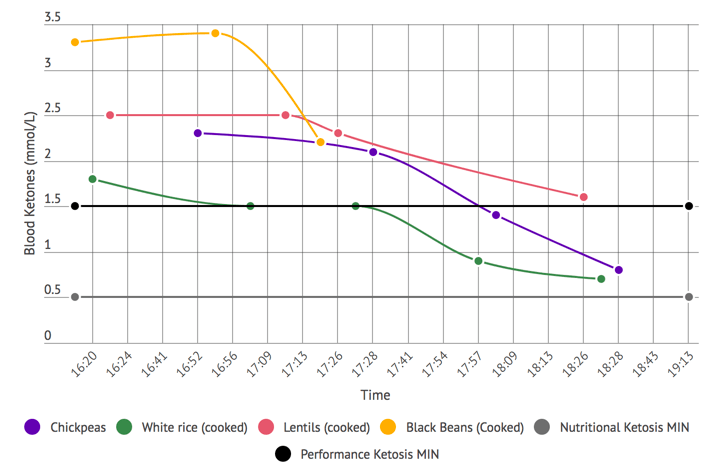

- First, as I’m on a ketogenic diet, I also tracked blood ketones to understand the impact of each carbohydrate source on my levels of ketosis.Did a particular carb drop me below the performance ketosis threshold (1.5 mmol/L)1? Or did it drop be below the nutritional ketosis threshold (0.5 mmmol/L)?

- Second, from my using a Continuous Glucose Monitor for the last 3 months I know that my blood glucose readings in the mornings are not stable. They rise and fall after waking very predictably, but to greater or lesser amounts depending on sleep, stress and possibly other factors.On the other hand, since I only eat once a day typically, at my evening meal, I know that my blood glucose in the afternoons is always flatline. So I ran my experiments in the afternoon knowing that the variables were better controlled. This is not the situation for most people as Robb describes in his book, so you are most likely better off running the test in the morning as he advises.

In my case the takeaways from this self-experiment were:

- Lentils had the least impact on my blood glucose levels and ketone levels. My blood glucose had dropped back to near baseline, below 90 mg/dl, within 90 minutes.

- White rice had the largest relative impact on my glucose levels, but didn’t necessarily have the largest impact on my blood ketone levels. It was the only carb for which I found myself ‘carbohydrate intolerant’, as it failed to return below the 115 mg/dl cut off mark. It also had potentially not even peaked at the 2-hour mark. It was still rising as of last reading, and was just over 130 mg/dl.

Blood Glucose Response to 50g of Effective Carbohydrate

Blood Ketone Response to 50g of Effective Carbohydrate

Notes for Context & Additional Observations

- Average readings of two or three blood glucose readings were taken for each blood glucose data point. From discussions with blood meter manufacturers I’ve learned that blood glucose meters have a high variance in their readings, so when you want accurate results you need to take several readings depending on the variance of the readings (two readings if the first two readings are < 0.5 mmol apart, or three readings if they are over 0.5 mmol apart). Researchers I’ve spoken to also follow this protocol to normalize readings.

- Unfortunately I ran out of ketone strips for the last experiment which was the black beans. This was particularly annoying since the ketone response looked pretty unique for these – so I will likely rerun this particular test in future (especially as I dabble in black beans at Chipotle every once in a while).

- I experienced some gut intolerance/ some negative symptoms from the lentils. This was the only carb that I experienced this with and seems to go against some assumptions that autoimmune/ auto-inflammatory responses are behind the largest glycemic responses to foods. The glycemic response in my case, was the lowest for lentils while it was the only one I experienced gut intolerance with.

Sleep

- Tool/ Tactic: Sleep is the most important physiological parameter, and poor sleep or inadequate sleep is excessively damaging to the body. Robb argues that if one feels good when going to sleep and waking up, then this is a reasonable indication that the body is performing in healthy shape. Tactics for improving sleep quality from Robb’s blog include: reducing light saturation, reducing noise in the environment, doing intense exercise earlier in the day (due to potential shift in circadian rhythm with late evening exercise), stopping all work a few hours before sleep and making a list of your thoughts before going to sleep – then agreeing with yourself that you are best able to take care of this list after a good night sleep.

- Tracking: In Robb’s opinion, it is key to subjectively track physiological concepts in our bodies and to make use of understanding these perceptions. For example, this entails paying attention to feeling tired before or rested after sleeping, or feeling background symptoms of inflammation (eg. in the joints). Robb discusses the use of Heart Rate Variability (HRV) for tracking sleep quality in his blog.

Tracking

Biomarkers

- Waist to Hip Ratio: Anthropomorphic body markers, such as waist to hip ratio, body weight, or Body Mass Index (BMI) are useful for understanding carbohydrate tolerance, ex. as a complement to evaluating 7 Day Carb Test after a diet intervention. However, anthropomorphic markers are not very specific measures of insulin resistance. For example, people who are lean still face carb toxicity. Alternatively, people also sometimes face inflammation caused by the immune responses to other specific food types, ex. eggs or soy.

- Fasting Blood Glucose: Elevated fasting glucose levels indicate a progression toward diabetes. Fasting glucose is usually taken first thing in the morning after an 8 hour fasting period and optimum levels range between 70 and 90 mg/dL.

- Hemoglobin A1C: Used to identify the average plasma glucose concentration over prolonged periods. Higher levels of hemoglobin (A1C) indicate poorer control of blood glucose levels. Normal levels are less than 5.7%, pre-diabetes levels range between 5.7 to 6.4%, while higher than 6.4% is indicative of diabetes. Both fasting glucose levels and hemoglobin A1C are useful in identifying a level of blood sugar dysregulation, but cannot be used to quantify insulin resistance at an individual level.

- HDL & LDL Cholesterol: High – Density Lipoprotein (HDL) is the traditional measure of ‘good cholesterol’ used by doctors and healthcare. Levels above 60 mg/dL are considered protective of cardiovascular disease. Low – Density Lipoprotein (LDL)) is the traditional measure of ‘bad cholesterol’ – the type which causes cardiovascular disease. Less than 100 mg/dL is considered an optimal level, while levels between 160-189 mg/dL increase the risk for cardiovascular disease. While both measures are important biomarkers, these are not indicative of insulin resistance status.

- LPIR (Lipoprotein Insulin Resistance) Score: The LPIR Score is constructed as a weighted combination of 6 lipoprotein subclass measures and reflects the concentrations of each into one score. The final result ranges from 0 (most insulin sensitive) to 100 (most insulin resistant). Recent studies have been using the LPIR as a more accurate approach to assessing insulin resistance improvements via interventions.2

- GlycA: A novel biomarker useful for predicting predisposition to insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes3, cardiovascular diseses4 and inflammation-driven diseases including cancer5. Normal GlycA levels are below 400 μmol/L. Concentrations tested above this cut-off value are considered high and indicate the need to take steps towards preventing health issues.

- Ferritin: Serum ferritin acts as a buffer against iron deficiency and iron overload. Levels are measured in medical laboratories as part of the workup for detecting iron-deficiency anemia. The ferritin levels measured usually have a direct correlation with the total amount of iron stored in the body. Female normal reference range is 12-150 ng/mL and for males it is 12-300 ng/mL.

- Hematocrit: The hematocrit (Ht) is the volume percentage (vol%) of red blood cells in the blood. It is normally 45% for men and 40% for women. Robb checks ferriting and hematocrit as markers for tracking iron saturation which he plans to tackle by experimenting with donating blood and because these are useful in determining iron saturation which he suspects is the potential cause of some inflammation.

Lab Tests, Devices and Apps

- NMR Lipoprofile: The LPIR score is part of the NMR Lipoprofile run by Labcorp (example report output here). It is an additional biomarker that was added to the panel more recently. The NMR Lipoprofile was originally run by the company LipoScience, which was acquired by Labcorp. As a result, Labcorp is now the company that runs the most advanced labs using NMR Lipoprotein analysis.

- GlycA Test: The GlycA test is also offered by the company LabCorp.

- BioForce HRV Set: BioForce HRV is a for tracking HRV which allows users to include their choice of sensors. There is a standard Bluetooth heart rate strap or a newly developed and finger sensor. Both sensors are compatible with all iOS and most Android devices and are constructed to deliver the precision necessary for accurate HRV measurements.

Tools & Tactics

Diet & Nutrition

- 30 Day Diet Reset: A diet scheme based largely on a Paleo diet type template, aimed at healing the gut and re-normalizing the neuroregulation of appetite. Following Robb’s guidance in Wired to Eat, the 30 Day Diet Reset should be done before the 7 Day Carb Test such that the results of the test can be objective.

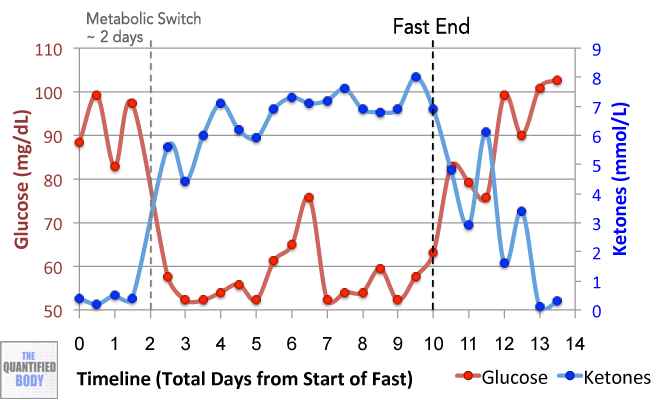

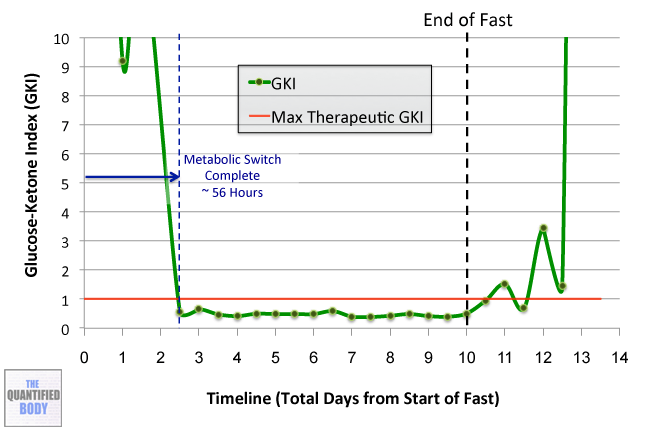

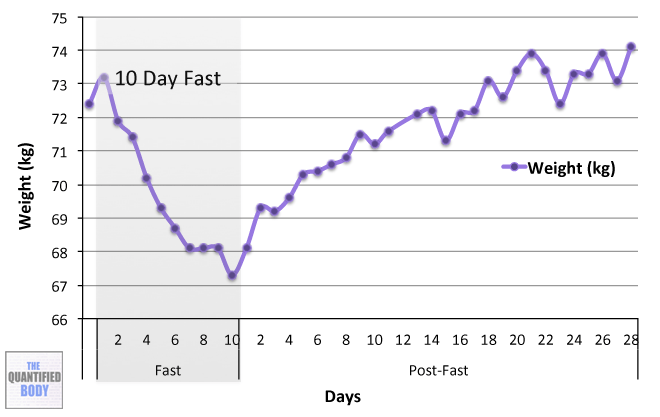

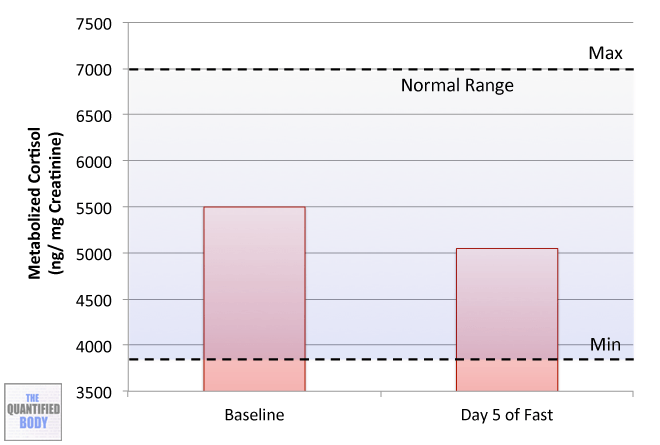

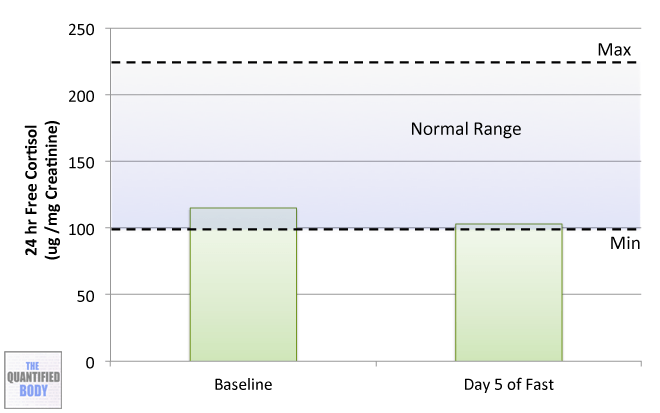

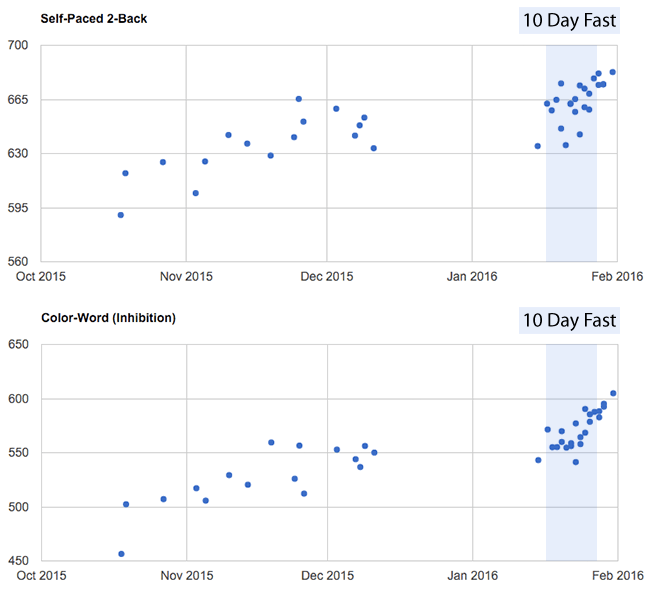

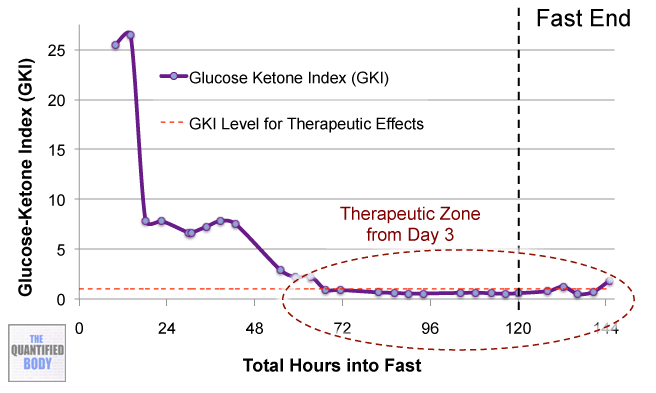

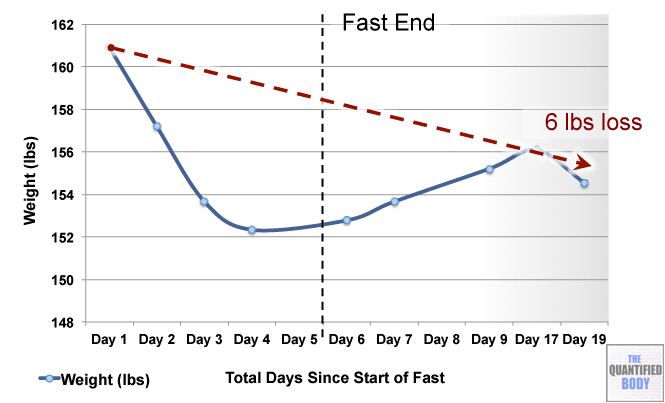

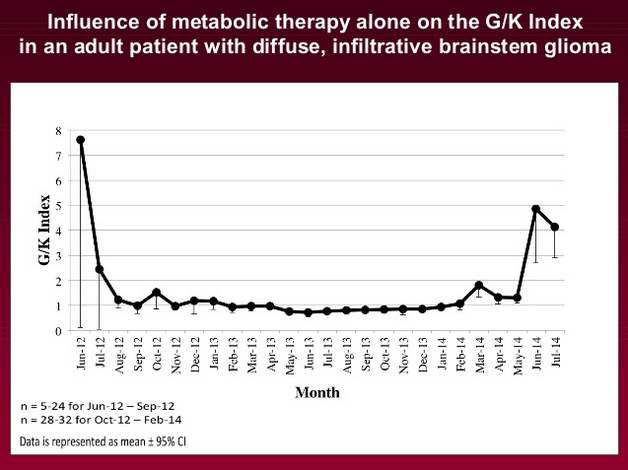

- Fasting: Damien has seen improvements in his carb tolerance with the use of fasting as a tool in various formats. Having tracked his glucose and ketone levels, he concludes that the switching point of burning ketones, instead of glucose, occurs at approximately the 72-hour mark. Over several fasts, it becomes easier on the body to switch to ketogenic (therapeutic) ranges with the switch occurring quicker (e.g. 48-hour mark). The glucose/ketone ratio charts look flatter indicating a more controlled physiological response to fasting.6

- Ketogenic Diet: A diet which restricts carbohydrate intake, over time causing the body to switch from using glucose to burning ketones as the main fuel. There are many potential benefits from ketogenic dieting. For most people who are overweight and insulin resistant, a lower carb intervention wins out as an approach to solving these health issues. A therapeutic state of ketosis is determined by reading fasting blood glucose levels (which should be below 80 mg/dL in the morning after 8h of no food intake), while β-hydroxybutyrate (blood ketones) should be higher than 0.8 mmol/L. See Episode 7 with Jimmy Moore on optimizing ketogenic diets.

Interventions

- Donating Blood: Robb plans to experiment with donating blood, with the aim to reduce some potential low-grade inflammation caused by iron overload. He plans to track iron saturation before and after 3 months of donating blood on a consistent basis and reach conclusions based on the data. Robb compares his case to Chris Masterjohn who personally controls an iron toxicity predisposition by optimizing his blood donation schedule. Chris discusses this topic in Episode 46 of this show, an episode focused on micronutrient status optimization.

Tech & Devices

- Blue Light Blocking Glasses: FDA registered blue light blocking glasses used for digital light eye strain prevention. These glasses are a useful way to reduce light saturation for a few hours a night before going to sleep.

Other People, Books & Resources

People

- Christopher Kelly: An athlete and founder of Nourish Balance Thrive which is a service offering a science-based, personalized support program to help people regain optimal performance.

- Marty Kendall: An engineer with an interest in nutrition who seeks things numerically who founded Optimizing Nutrition. Marty aims to consolidate a range of paleo and ketogenic ideas into an algorithm that will enable an individual to tailor their diet and bring about health goals.

- Tim Ferriss: An all-round successful man, who runs a podcast focused on deconstructing world-class performers – other successful people in various niches or businesses. His podcast is often ranked #1 across all of iTunes and is also selected for “Best of iTunes” for three years and running. Robb interviewed Tim in an episode of his podcast.

- Joel Jamieson: Joel Jamieson is considered among authority figures on strength and conditioning for combat sports and has trained many athletes since 2004. Joel stands behind the BioForceHRV project, aimed at tracking HRV and implementing it in optimizing exercise to the condition of your body. Joel introduced Robb to the BioForce tracking platform which he has used ever since.

- Alessandro Ferretti: An optimum nutrition researcher who formed Equilibria Health Ltd, which is now recognized as one of the leading providers of nutrition education in the UK. Alessandro actively does Judo and Karate and has discovered that he performs efficiently with a ketogenic diet – meaning feeling energetic, being able to undertake fasts, and remain lean.

- Bill Lagakos: A biochemistry professor focused on circadian rhythms and nutrition. Following on Bill’s work, Robb has adjusted his diet to time-restricted eating, meaning that shortened feeding windows are assumed to be beneficial for a variety of physiological reasons. Moreover, based on his research in biological (circadian) rhythms, Bill Lagos advocates the idea that more carbohydrates should be eaten earlier in the day, such that carbohydrate backloading can be avoided. Because of these reasons, Robb has adjusted his fasts to approximately 14-16h, whereas before he would 18h fasts. Following a fast Robb eats a robust full meal, but he usually times this with jiu-jitsu exercise 2-3 hours later. This is an example of optimizing both how diet volume and the intensity of exercise.

- Chris Masterjohn: Robb appreciates Chris’s ability to dive into the biochemistry and pathophysiology of when things are right and wrong in the body, as well as to develop whole food and supplement solutions based on his research. Chris was a guest on our show in Episode 46.

- William Cromwell: A physical chemist who studied NMR spectra technology lipoproteins, serving as Director of Cardiovascular Disease at LabCorp.

Books

- The Paleo Solution: A book by Robb Wolf following his perspective as both scientist and coach on the benefits of Paleo dieting, and this along with exercise and lifestyle changes can change one’s appearance and health for the better.

- Wired to Eat: A book written by Robb which starts with the 30-Day Reset to help people restore normalized blood sugar levels, repair appetite regulation, and reverse insulin resistance. This book also features standard Paleo – based recipes and meal plans for people who suffer from autoimmune diseases, as well as advice on eating a ketogenic diet.

- Myth of Stress: A book explaining how much of what we perceive as stressful in day-to-day life is actually generated by our brain’s anxiety response, but is not actually a legitimate stressor in terms of evolutionary times scenarios, when our brains evolved the stress response. Robb interviewed author Andrew Bernstein in an episode of his podcast.

Other

- I, Caveman Show: Robb took part in this Discovery Channel reality show where they had to live mimicking the stone – age hunters and gatherers. It took place at 8,500 feet in the Colorado Mountains.

Full Interview Transcript

[Robb Wolf]: Hey, huge honor to be here, thanks.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, it’s a huge honor on my side, because you got me back into eating meat back in 2010, just as we discussed a few minutes ago. That was great and that vastly improved my health, so thank you for that.

[Robb Wolf]: Awesome, awesome.

(0:04:01) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So you just released this book, Wired to Eat, which I went through, and it’s building on what you’ve done in the past, and also looking at some of the things you’ve learned over time with all the practical experience you’ve had implementing this.

What would you say is basically the crux behind this book? Is it the neuroregulation of appetite, or how would you think about it?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, it’s kind of two pieces. So the front of the book is really starting this conversation from the perspective of the neuroregulation of appetite.

So I’m kind of known as being one of the Paleo guys, and I definitely use that evolutionary biology, evolutionary medicine framework to inform the question and answer process that I bring to strength and conditioning and nutrition, and what have you, but it’s a starting place. It’s not the endpoint.

And I think that’s where, in some ways, the efficacy of that whole methodology has been lost. People assume that that’s where you start and stop. Whereas for me it’s always been this is the starting place.

We’re not yet able to take a Star Trek type scanner and run it from toenails to earlobes and then say okay you need to eat this and train this way. Stuff like that may happen eventually, but we’re still very much in this empirical process.

So then if we’re in this empirical experimentation process, where the heck do you start? And I throw out this really insane, over-the-top, greasy used-car salesman notion that maybe evolutionary biology can inform some of where we start this health and performance story from.

There’s this model in evolutionary biology called the Discordance Theory. That’s basically you have an organism that is pretty well matched for it’s environment. The environment can be the weather, the food, it can be a ton of different factors, it could be bacterial or parasitical. But if things change, it could be beneficial, negative, or it could be neutral.

But if we start seeing disease processes prop up that we don’t see in the natural free-living environment, or in the pre-environmental change story, then maybe there’s something to be learned from that. That’s my crazy suggestion is that possibly our genetics are wired up for a life way and a time that no longer exists, and that as great as so many of the elements of modern civilization are, there might be downsides to it.

For example, antibiotics are amazing for preventing septic illness and death, but there might be some downsides related to mitochondrial function in our own bodies, and then changes in our gut microbiome, which we’re now understanding may have huge implications for our overall health.

Again, I use this as an orientation tool. And at the beginning of Wired to Eat I’m laying that foundation with the neuoregulation of appetite. Really trying to understand if we looked at high carb diets or low carb diets, what are the things that allow people to eat in a way that they support their activity level, support a healthy body composition but tend not to overeat.

And there are some commonalities there. The efficacy of some of these nutritional approaches becomes really obvious why they work when we better understand the neuroregulation of appetite.

And the goal on the front end of this – and it’s kind of funny because it’s fairly touchy feeling stuff – but my real goal is to help people understand that it’s not your fault if you find it difficult living in the modern world and navigating the snack aisle of the supermarket. It’s totally reasonable and understandable.

Now I’m not one of the fat accepting guys either. I do recognize that overweight and metabolic issues are damaging to our health. They are a huge cost to society.

So I’m not recommending that we just roll over and die and let life have it’s way with us, but I’m suggesting that if we can unpack all that emotional baggage and understand that this process might be hard but it’s doable, then we’re starting off at a good footing.

And then the implementation part of the book is where we get really granular in a more progressive fashion. We start things off with a triage process where we do some subjective elements, such as asking how do you feel between meals, what’s your cognitive function like, how long can you go between meals and still maintain good physical and cognitive performance.

And then we get more specific. We look at things like the waist to hip ratio, we look at fasting blood glucose. We really lean heavily on this thing called the LPIR score, the lipoprotein insulin resistance score, because for me it’s kind of the most powerful direct means for understanding where we are on this insulin sensitivity insulin resistance spectrum.

And if we are more insulin resistance then we tend to do better on a lower carb intake. And there’s a lot of variability with that. But we also have people that are overweight or experiencing some other health related issues but they are actually insulin sensitive, and these are the people that tend to do better on that moderate to high protein, high carb, low fat diet. So there are examples of both ends of this spectrum working pretty well.

But we use this triage process to get a handle on where we are in that insulin sensitivity insulin resistance spectrum. We use a 30 day reset, based largely around a Paleo diet type template, to heal the gut, re-normalize the neuroregulation of appetite. And then from there we use the 7 Day Carb Test.

There we pick a battery of different carb foods and we eat an allotted amount, which is 50 grams of effective carbohydrate. We check our blood glucose at a two hour mark. If your blood glucose is at or below a certain level, that’s usually an indicator that’s a good amount and type of carb for you.

If it’s above that, then we start asking some questions about should we reduce the portion size or is this really a good food for you. Because sometimes our elevated blood glucose level is not just from the carbohydrate content of the food but it’s from the immunogentic properties of the food.

If someone is reactive to wheat or eggs or soy, they may actually get a significantly elevated blood glucose response. And it’s not from carbohydrate, it’s from the stress response that occurs when we eat a food that we have an immunogenic response.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thanks Robb. A real big download there.

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, that was… (laughter)

(0:10:46) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Let’s talk about a couple of the things you mentioned that stood out.

First of all you were talking about insulin resistance.

Do you see this as one of the cruxes of the issues? Is this one of the main factors? I know you’ve had a lot of practical experience in clinics and studies, and so on. So what have you seen in the populations out there in terms of how important the insulin resistant piece is?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah. And this is a really contentious topis because people are still in pissing and squabbling matches about what brings about insulin resistance. Is it just in response to elevated insulin levels?

I think it was an interesting theory but over the course of time that has not borne out to be the best theory. It still seems to relate to an overabundance of energy causing systemic inflammatory responses within the cells that then tends to up-regulate this insulin resistant response.

But once the person is insulin resistant, particularly when they are heading down this road towards prediabetes and potentially diabetes, there is without a doubt one intervention that seems to work remarkably well. That’s reducing carbohydrate level to a point where it’s no longer toxic to the individual.

My analogy to this is basically photo exposure in getting a sunburn. Depending on what type of skin pigmentation you have you will be able to handle greater or lesser amounts of UV radiation before you get a sunburn. And if you do have a sunburn, there’s really only one intervention that makes sense, and that’s to reduce your exposure to the toxic levels of UV radiation.

And so that insulin resistance and the resulting metabolic derangement, which includes but definitely isn’t limited to elevated blood glucose levels, you can tackle that in a variety of ways. You can starve people down on a high carb low fat diet, and it can work. But in that insulin resistant state we tend to have a really serious dysregulation of the appetite and the tendency to want to eat a lot of carbohydrate.

And so this is where for most people who are overweight and insulin resistant that lower carb approach seems to work pretty magically. Even in these free-living populations where people can make a variety of choices, the lower carb intervention tends to win out.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I guess that refers to the saying carb-cravings, that we often hear.

I don’t know if you’ve seen this, but some people have a lot of difficulty with fasting. They’ll have dreams about food if they fast for 24 hours. I know friends who have fasted with me [for whom] it was a bit difficult. Or they get ‘hangry’ – I know that’s a term you coined in your book as well.

Have you found that that correlates with some of the lab tests? Is that kind of a symptom of potential insulin resistance?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah. So here’s a good example of this.

My wife and I did this 7 Day Carb Test, and we’ve known empirically that I just don’t do as well with carbs.

I remain 100 percent gluten free because if I get a gluten dose, the first bathroom I hit will require a priest, an exorcism, and probably needs to be bricked over and never used again. So there’s no upside to consuming gluten such that I willingly do it. I get some cross-contamination stuff occasionally.

But I’ll have a little rice, or some corn, here and there. We’ll go to Mexican food or Thai food and I’ll kick my heels up once in a while. And I usually feel pretty rough. And I may feel rough for a day or two afterward.

Whereas my wife, I’ll ask her, “Hey are you feeling kind of carb headed from that?” And she says, “Yeah, it lasted for 20 minutes.” I wonder what’s going on with that.

And so we dug into that deeper, using this 7 Day Carb Test. And we ate the same amount of carbs – 50 grams of effective carbohydrate — and we picked the same foods. It was, white rice, white potatoes, sweet potatoes, applesauce, gluten-free bread, and a couple other items. And it was really interesting.

So with the white rice, at two hours post-meal my blood glucose was still in the 180s, damn near diabetic levels. Terrible. And I felt terrible. And Nicki at two hours was a 121, 122 or something like that. Just across the board, she had remarkably better blood glucose levels than I did.

So that was interesting, and it was kind of validative of what we had seen previously. So then kind of out of nowhere she said, “Hey, I’m going to do a dinner to dinner fast.” I was like, okay, that sounds good. We’ll check that out. And it was interesting.

So she did her dinner, and didn’t eat again the following morning. She worked out. We have a 10 month old Rhodesian ridgeback puppy that requires a ton of training, and she’s really diligent in training the dog, but it’s active. So she did her workout and then she’s running the dog around.

And we have two daughters under the age of five. So it’s a really active life that we both live, and particularly my wife being at home in that scene most of the time. By 23 hours she was getting hungry, but she was still totally cognitively on point. She felt good.

Right at that 24 hour mark we checked her blood glucose level, which was 71. That’s low, but a good low, particularly for a fasting scenario. And her ketones were at a 0.8. So she was already in a therapeutic ketosis range. And she was effectively just right at that 24 hour mark.

This is something that we just don’t see all that often in Westernized populations. This exact type of study hasn’t really been done specifically in hunter-gatherers and pre-Westernized societies, but what we see in those situations is these folks may go a day or two without eating.

They are hungry, they are definitely wanting to eat, but they don’t have a decrease in physical performance or cognitive function. You aren’t a very effective hunter-gatherer or horticulturalist if you are leaning against a tree drooling on yourself because you are in metabolic shutdown because you have to eat every two hours to keep yourself going.

So your question was — and I know that this is the longest answer to the shortest question in history. I seem to be good for that. But the question, was do we see specific lab values that tie into this?

What I’ve noticed is a tendency towards, if you are more insulin sensitive – and that will be determined by your total choleric load, your stress load, your sleep, your gut microbiome. There are lots of factors that go into that.

But if you tend to be more insulin sensitive, we tend to see more metabolic flexibility. If you have a higher carb meal, it doesn’t really knock you out and you don’t get super high blood glucose levels. You don’t have hypoglycemic crashes. And on the flip-side of that, if you need to go 6, 10, 12, 24 hours without eating, you may be hungry but you are still functional.

Whereas that insulin resistant individual, they do a piss poor job of dealing with large carbohydrate boluses. They get a super high blood glucose level, they get a rebound hypoglycemic response. And then when they have carbohydrates restricted significantly, the first couple of days – usually 72 hours – they’re in hell, because they have neither adequate glucose to fuel what’s going on and they’ve not yet kicked over to converting fats into ketone bodies in an effective way.

There are hormonally driven elements to this, and then there are also possibly mitochondrial considerations, where the mitochondria themselves may be damaged to a degree. It’s like taking a lawnmower that’s been out in the garage for two years, and it’s got some water in the carburetor and you just have to really rip the cord on that thing to get it to turn over and start using the fuel that you want it to use.

So let me know if I answered that. I know it was a long, rambly story.

(0:18:50) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, I think you really did. Out of interest, because you noted that your blood sugar spiked to 180, how long have you been low carb for?

In a sense it seems like it’s not therapeutic, even if you’ve been low carb and Paleo for a long time, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to mend these type of things, this dysregulation when you eat some rice.

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, it’s interesting. Over the course of time, I’ve been able to push that carb tolerance up.

So now on my heavier Brazilian jiu-jitsu days I’ll be somewhere between 120-150 grams of carbs, and I do fine with that. But I also keep an eye on the types, and then I tend to put more of the carbs in the post-workout period, and similar to that. Whereas before 120 grams of carbs would have just crushed me.

So I’ve definitely recovered a lot, relative to where I was previously. And I’m still tinkering. I’m not sure if there’s still some gut health considerations. I’m actually just getting ready to start donating blood on a consistent fashion, because of some thoughts around some potential low-grade inflammation from iron overload.

So I’m going to play with that, and what I’ll do with that is I’ll probably go through three months of consistently donating blood, check the before and after numbers with regards to ferritin and iron saturation, hematocrit. And if we get to whatever delta we get from the start and the finish with that, then I’m going to revisit this 7 Day Carb Test and see if we get some improvements on that.

So that might be one final stone that I need to turn over and explore. I know Chris Masterjohn had talked about really reversing some significant insulin resistance. He had no idea what was going on, and he felt it was largely driven by that iron overload status.

(0:21:05) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow, that’s interesting.

I have iron overload as well, and many other things like infections. So for me it’s a bit difficult to pinpoint what it is. But my carb tolerance has got a lot better with fasts.

So I’ve tracked with fasts, and I’ve seen that switching point you were just talking about, the 72 hours. It gets a lot easier and would happen a lot quicker as well. My ketones would go up faster, and glucose would go down quicker. And it’s been flatter over time. So it’s really, really interesting.

So you mentioned another panel just a bit earlier, a lipoprotein insulin resistance panel. What’s that?

[Robb Wolf]: So people are usually familiar with HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol. The cholesterol is a fat soluble, not water soluble, substance. So it would be like trying to mix oil and water together; it just doesn’t work that well.

But we need to move these substances around the body, so there are these things called lipoproteins, which actually are the vehicle that carries the cholesterol passenger around the body. And triglycerides are also, to some degree, carried around [by these], although they have their own carrier molecule as well. But these lipoproteins usually correlate pretty directly with the amount of cholesterol that we have, both HDL and LDL cholesterol, but not always.

There are certain folks that exhibit this phenomena called discordance, where you may have lots and lots of small dense lipoprotein particles and then a relatively low cholesterol level. And these are the folks that often, like a 35 year old triathlete and they work out all the time but they’re also a shift working firefighter or something and they suffer a heart attack at age 35 or 40.

And it’s like, wow, we never saw that coming. Their triglyceride to HDL ratio looks pretty good, which is a decent correlate or indicator of insulin sensitivity. And then their total cholesterol levels didn’t look that high, but under the hood looking deeper the lipoprotein numbers were super high.

And so there’s also a way that we can look at the lipoprotein numbers and their relative ratios. And there have been some really phenomenal correlation studies to tie this link together so that we can tie that lipoprotein insulin resistant score to the real world.

And there are some other methods for tracking that. There’s looking at fasting blood glucose, but there are limitations to that. There are ways that that can be misinterpreted both on the up and the downside. Fasting insulin is similar, it’s helpful but there are ways that can be circumvented. A1C [is another].

So we do like looking at several of these numbers, in the beginning in particular, and then checking back on them periodically, because it provides a lens. In particular a lens to help us better understand that 7 Day Carb Test. Because those carbohydrate numbers just in isolation can also be a little bit confusing.

But with that lipoprotein insulin resistant score, what we found in the police and fire populations that we work with – I’m on the Board of Directors of the Medical Clinic here in Reno, Nevada – we found that with the other methods for tracking insulin resistance we were missing people, particularly folks that were sleep-deprived and/or hyper-vigilante.

So they had consistent adrenal cortical response, some HPT axis dysregulation. Those people were insulin resistant, and often times significantly so, but we didn’t see it in fasting insulin levels. Specifically blood glucose levels may not have been that bad at that point, but we were seeing some really consistent long term insulin resistance when we looked at that LPIR score.

(0:24:28) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So it sounds like it could be uncovering people that we normally miss.

How about the waist to hip ratio? That’s a nice easy thing that anyone can do at home. Did you also find the same thing, that it doesn’t necessarily capture people? Like you can be pretty thin and slim and have these same issues.

(0:24:53) [Robb Wolf]: Absolutely, and that’s where again we use it to build a case, but you can’t hang your hat 100 percent on anthropometric measures like that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. Have you looked at how people can basically recover carb tolerance? Or have you seen that kind of period, the timeline?

Any indication of, say they did a 7 Day Carb Test now, when would it be useful to retest? Maybe 6 months after following a clear Paleo diet and all of your proscriptions. You talk about all of them.

[Robb Wolf]: That’s a really good question. Part of the inspiration for even doing the 7 Day Carb Test came out of research from the Weizmann Institute in Israel, and it was looking at personalized nutrition by tracking the individual glycemic response.

And what they did in these folks is they had them wear a CGM, a continuous blood glucose monitor – just a little disk that gets slapped on the back of your arm – and it measures your blood glucose levels once a minute, every minute for the duration of the test. I forget, but it was two or three weeks and they had 800 people signed up on the study.

So it was a massive amount of data; they had over a million blood glucose samples. They then did a gut microbiome sequencing on these folks, they did a full genetic analysis, and the standard kind of lipidology based blood work. And then they started feeding these people different meals. And the blood glucose responses were all over the map.

It was similar to myself and my wife, where one person would eat white rice and [their] blood glucose would go to the moon, [whereas] another person would eat white rice and they had a barely perceptible increase in their blood glucose response.

And then there were wacky things like hummus. Even though I’m the Paleo guy and legumes are theoretically problematic, hummus is protein and fat and fiber. There’s hardly any carbohydrate to it, but hummus was about a coin toss as to whether or not you had a good or a bad blood glucose response.

And the one thing that they did figure out with this was that if you determine the amounts and types of food that kept your blood glucose within lower bound levels, then your gut microbiome tended to improve and your inflammation and insulin sensitivity tended to improve over time.

So I don’t know that I have an exact timeline on this that I could relate, but what appears to happen is if you eat in a way where you’re not consistently deranging your blood glucose, which seems to have knock-on effects with the gut microbiome. There are some interesting theories around how acellular or processed carbohydrate can shift the way that our gut microbiome is existing. It’s a pretty interesting and elegant model.

But if you keep things within good bounds, then things tend to improve in kind of a virtuous cycle, and then conversely if you are consistently driving blood glucose out of what we would consider to be healthy bound, the gut microbiome tends to shift towards a more pro-inflammatory state. We see elevated inflammatory cytokines on circulation, we tend to see elevations in insulin resistance.

And in the book I make a recommendation that maybe quarterly. We don’t necessarily need to do a full reset as far as a 7 Day Carb Test, but I really recommend sitting down and just paying attention.

“Hey, how long can I go between meals and still feel good? If I do a little bit of fasting training, how do I feel with that? How’s my sleep? What’s my creakiness in my joints, what’s my subjective measures of inflammation?”

I am fairly geeked-out on the quantified self stuff, and I find a lot of it valuable, but I still like to get people back in their own skin so they can get a sense of where things are going right or potentially going wrong.

And a quarterly recheck, at least on the subjective level, seems to be frequent enough that if things are sliding sideways we haven’t slid so far that it’s terribly hard to get things back on a good track. But it’s also not so frequent that you just throw your hands up in disgust and you’re just done with the whole process and don’t pay attention to anything anymore.

(0:29:39) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, absolutely. On my own journey I’ve quantified so much stuff, but at the end of the day it’s how you feel that matters. And you can even improve a whole bunch of biomarkers, but if you don’t feel better or feel less inflammation it’s not that helpful. It can be insightful and give you clues, but we’re still at quite a rudimentary level yet.

I actually interviewed Eran Segal in just the last episode of this podcast, actually. He inspired me to get into CGM, amongst some other people. So ever since I’ve been playing around that and have found it very instructive.

And not just for the food intake, but also sleep, which you talk about a lot in your book, and stress.

How important do you think those are in your experience, compared to the food? Because we always talk about the carbs and the food.

[Robb Wolf]: Even though I’m the food guy and we used to run a gym, so you would think that I would say that exercise is most important, or exercise and nutrition, but sleep is it. I mean, sleep is it. And here’s my argument for that.

You could eat the most wretched diet imaginable, and it’s going to be hard for you to kill yourself in anything short of a couple of decades. Some people can do it, but it takes a pretty Herculean effort to do yourself in with even the worst dietary practices you can imagine.

But sleep-deprivation is so injurious to our physiology that the Guinness Book of World Records, they will let you jump a rocket motorcycle across the Grand Canyon, they’ll let you juggle chainsaws that are lit on fire, but they will no longer entertain people trying to do unbroken longer periods of sleep-deprivation. The last two people that have tried it, they got right around that 9 to 11 day mark and they just died. And they don’t know why, but they are dead rather quickly.

So the sleep piece is just so incredibly important. The stress piece is important too, but there was a great book that I read and I interviewed the author, it’s called the Myth of Stress. It was really a fascinating reframing of this whole stress story. And so much of what we experience in day-to-day life that we perceive to be stress is completely generated between our own ears.

It’s anxiety about finances, it’s anxiety about how this meeting is going to go with our boss. It’s all these different things that really at the end of the day, we have an opportunity to either let this stuff eat us alive, or we can reframe it and just say that’s not actually a real threat, and so I don’t have anything to be worried about. So there’s actually comparatively little in the modern world that is in fact a legit stressor.

Now the caveat with that, we do a lot of work with police, military and fire, and those folks legitimately live in hyper-vigilant states a lot, because they have life-or-death scenarios that they’re dealing with every day all the time. So there are caveats to that.

But a shlep like me, where I live out on a small farm, we have some animals, I have two kids, I do the business stuff that I do, I can let myself get spun up and feel stressed out. Like, oh my god, one of the goats got bit by the neighbor’s dog.

This did happen this time last year, and the poor goat it’s eat got peeled off. But it was fine, we had a vet come out and gave it some antibiotics. We had to catch the little bugger and wrap it’s ear up for about a week, and then he was totally fine.

But when it first went down, I was like, why did we ever move out here, what are we doing, this is a waste of my time. And all this just internal dialogue and stress. Then I stopped and I was like, well I love living here. The kids love the animals.

There’s sometimes pain in the ass elements to this, but I’ve turned this from an acute event into what is now for me a long-term stressor, but I did it to myself. So I would throw out there that a lot of what we perceive to be stress is mainly self-generated.

And again, circling back to the sleep part, I just can’t think of a greater return on investment than trying to go to bed a little earlier, sleep a little longer, within the boundaries of what’s normal for you. Just blackout your room, have a really solid sleep hygiene process where you go to the bed at the same time each night.

It may not do wonders for your social life, but then again maybe it will because you may not be a cranky cantankerous prick because you’re actually well rested. So it’s hard to tell. And it’s liable to pull 5 years of aging off of you in just a matter of a week.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. Sleep is the hardest part.

Just curious, do you use anything to track your sleep? To try and keep a bit more responsible, or have you seen anything that works for people?

[Robb Wolf]: Really HRV is kind of the best thing that I’ve seen. Some of these actigraphy things are interesting. It is interesting, again, even though I’m a biochemist, I don’t know if I’ve weighed and measured so many things that I’m just like, oh my god I don’t want to do it anymore.

But I’ve just gotten into a point now, and it’s interesting. Folks like Tim Ferriss and some other folks I’ve interviewed with, they were like, “What’s your morning ritual?” And because I have kids, the morning ritual is super variable. I don’t know if somebody pooped their pants, and they’ve got poop from their earlobes to their toenails. That’s a way different morning than if that doesn’t happen.

But what I have found is I tend to have really good control over my go-to-bed ritual. So when the sun goes down – and this varies with the seasons, our days get longer so we stay up later – but when the sun goes down then, we installed dimmer switches in our house when we did our remodel last year and we drop the lights down to a super low level. We put on some blue blocker Swannie sunglasses.

Usually not too long after that I do a little bit of reading and I just fall asleep. And it’s like a ninja blow dart hits me. And when I’m consistent with that, and if I also happen to be tracking my HRV pretty consistently, I just see that HRV score improve. And then if I do have an off-night of sleep, we see some pretty immediate impact on that.

But the actigraphy, I haven’t found to be super helpful. If we had someone that was waking up in the middle of the night or something like that and we had some HRV score feedback. The thing about HRV is it tells you something is up, but it doesn’t tell you what that thing is.

It could be that we’re having a low blood sugar response in the middle of the night, so we get some cortisol release, and that suppresses melatonin production, so it pops us up out of sleep. So maybe we need more calories overall, maybe we need more carbs near dinner. Maybe we need fewer carbs near dinner, because some people are experiencing that rebound hypoglycemic event.

There’s not a one size fits all answer with it, but in general I just kind of gauge [when] I wake up in the morning, I stand up [and see] do I feel clear headed, do my joints ache because of jiu-jitsu and being 45, or do I feel good? And if all of that stuff feels good, then I’m pretty good to go. And particularly if that HRV score just stays nice and consistent.

(0:36:41) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. I’ve been a fan of HRV also for a long time. I’ve been tracking it.

I also find it difficult, the same way you do. It captures everything, and if you’re someone who’s got some kind of chronic health or some issue like that on top of potentially not sleeping correctly, over-training. You’re doing Brazilian jiu-jitsu, so I’m sure that’s happened a few times.

And there are these different factors and you have to kind of piece the story together. But it can give you that overall number.

I’m just curious, what do you use, do you use a sort of an app or is there something specific you like because of convenience or something?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, I’m just kind of old school. Joel Jamieson hooked me up with the BioForce platform and I’ve pretty much just like hung out on that.

I know there are a lot of cool stuff out there and I do have a few others but I’m again, a little busy and kind of lazy with that stuff. I’ll check in on it occasionally, but it’s generally a deal where once I get a baseline established, and it’s a thing again that I know if I’m getting into bed, falling asleep, and waking up feeling good, everything else is fine.

And then on my training side I do a little strength and conditioning, a little bit of weight work, gymnastics, and also some low level cardio to support the Brazilian jiu-jitsu. I just keep my volume and intensity really modest on that. 80 percent of my rolling is more in a drilling and aerobic fashion, and about 20 percent is that white buffalo in the sky.

Like the 20 year old three stripe white belt is trying to take my head off my shoulders, and so it’s a battle for survival. But I don’t do too many of those. Maybe one day a week that there’s some pretty hard training that goes on.

And so long as I do that, everything is good. Everything is really, really good. I just try to make very small, incremental progress, in mainly the jiu-jitsu side, and so all of my strength work, all my conditioning work, all of that is of a remarkably low volume and intensity for the most part. Just to support jiu-jitsu.

If I feel the least bit knackered after a cardio session or something, I went too hard. Because I need to save that energy for rolling, and not for getting better at the Airdyne or something like that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

So when you’re talking about volume, how many hours are you doing of exercise, jiu-jitsu, and all kind of mixed together?

[Robb Wolf]: So jiu-jitsu is between three to five days a week, and usually an hour to two. Shorter classes if I’m time pressured, then I get the one hour class which is a mix of drilling and then a little bit of live rolling.

A couple days a week I usually will stay for a half hour to an hour of just continuous live rolling. I try to grab partners where we don’t set a timer and we just try to roll. We just try to keep moving, and it forces a pace that you could maintain for about an hour straight. And I really, really like that. You get lots of repetitions in in that regard.

And then as far as the weights and gymnastics stuff, I just drop in a little bit of gymnastics bodies, mobility and strength work during the course of my work day. Usually once a week I either squat or deadlift. Once a week I might do some heavier weighted press and pull weight room style stuff for the upper body.

But those weight room workouts, I warm up and I’m done in less than 20 minutes. Occasionally a little longer than that if I’m doing a lot of mobility work in between, but even then it’s not like I’m doing a CrossFit work out.

I have two minutes of rest between sets. I’ll do a set of weighted chins, a set of weighted dips, and then some weighted shoulder dislocates to work on my thoracic mobility in between those sets. So it’s not a frenetic pace.

And then the recovery cardio, I will go longer on that if I can. It may be 40 or 60 minutes occasionally, but a lot of those – my oldest daughter now is five years old and has gotten pretty good on her little dirt bike. So I will drive her and and myself over to a park right next to our house that has some dirt trails and she’ll ride her bike and I’ll run at a nice easy pace. So I’m outside and I’m spending time with my kids.

So there’s like somewhere between three and maybe eight hours a week of jiu-jitsu, there’s maybe two more hours total a week of weights and cardio. But I do try to do a ton of stuff. I’ll stick the younger kid in a backpack and go for a hike for as long as she will put up with it. We have a three acre farm where we have animals to deal with, and we just run around playing hide and seek, and stuff like that.

So I do a lot of physical activity running around with the kids, but in the gym stuff between jiu-jitsu and strength and conditioning and all that is less than 10 hours a week, for sure.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so you keep the intensity monitored.

I just looked up the Myth of Stress. Was that Andrew Bernstein?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, Andrew Bernstein.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. Bernstein. Cool. That sounds really, really interesting.

Does that tie in with the gratitude stuff? We hear a lot about gratitude and I’ve been practicing it for a little while. I think a lot of people have. Did he mention that at all?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah. He would be a great interview. He’s a solid guy, a really, really good guy.

(00:41:35) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. Excellent.

Okay. So I thought we’d also jump into a little bit of ketones, ketosis, and fasting, because I know you’ve played around with this yourself and your levels of carb. And it’s such a big topic at the moment.

You’ve spoken a bit about you can’t really do the really low carb and the Brazilian jiu-jitsu and that you can’t get away with it. What’s you overall feeling on the whole ketones and ketodiet?

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, the last chapter of the book is called Hammers, Drills, and Ketosis: the one tool your doctor will never use. Fortunately, that story is changing. Therapeutic fasting and ketogenic diets are incredibly powerful as potential adjuvants or adjuncts to things like epileptic treatments, potentially working in synergy with conventional cancer therapeutics.

Just huge potential there, but it’s crazy because you don’t see people get into huge pissing matches about whether or not you should use a hammer, a screwdriver, or a handsaw to get something done. If you’ve got a 2×4 and you want to cut it cleanly into two pieces, a hammer and a screwdriver are terrible options, the handsaw is a great option. There’s just not a lot of drama around that.

But then whether or not you should be higher carb or lower carb becomes this religious doctrine thing. And there is a little more nuance to it, there is a little more depth. But just empirically we’ve seen people do pretty well at the power athlete end of the spectrum, the real short time indexing end of the spectrum, and quite low carb.

And we’ve also seen some people doing this ultra-endurance work at a pretty good level going very low carb. And interestingly that looks like catering to the ATP creatine phosphate pathway and also mainly the aerobic pathway.

Where we have a kind of deadzone, a no-man’s land, appears to be these really glycalitically demanding sports like soccer and MMA and CrossFit and jiu-jitsu. And there’s just, man you don’t see a lot of just empirical success there. You see people like me that try, and try, and try.

There are a few examples, there are a few people out there that are figuring out how to do it. Probably the highest level, most sophisticated person I’ve seen looking at this problem is Alessandro Ferretti. He’s in the UK. Man, that guy is smart.

And he is just doing some shockingly interesting work looking at [it]. And he does Judo and Karate, so not exactly the same as Brazilian jiu-jitsu but he’s found he runs great on a ketogenic diet, he has great energy, he can fast, and he’s lean. All the stuff is great, but then he will get kind of adrenalized and burned out in the process of doing too much high-intensity activity.

And what he’s done is just try to map out the volume and the intensity of the training he will be doing, and then match that with a maltodextrin solution or maybe a maltodextrin plus fructose, because there are some arguments for repleting some of the hepatic glycogen preferentially. And he does some really amazing work.

Now, for me, because I’m kind of lazy, it also looks a little bit like a calculus problem. Alessandro is like six times smarter than I am, and he runs a really well done clinical intervention, where they’re just collecting tons of data on people.

I’m kind of a knuckle-dragger. So where I’ve arrived out with all the stuff is I just tend to eat between 75 to 120 grams of carbs a day. Higher end on training days, lower end on non-training days.

But the overall story I think is ketosis and fasting hold enormous therapeutic potential. Potentially some great performance enhancement under certain circumstances, but it’s also a powerful tool. And like any other powerful tool it can be misused, or inappropriately used.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, Absolutely. I know Alessandro, I talk to him quite often too. He’s a great guy. I have to get him on this show soon.

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah.

(0:45:35) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So thanks for all of this. Last thing on this carb thing is it doesn’t sound like you time your carbs at all before or after training, or anything like that. It sounds like you’re very much focused on the practical, which is probably 80 percent of society who aren’t super self-disciplined and robotic about this.

[Robb Wolf]: Yeah, I do time it a fair amount, in following a guy Bill Lagakos. He’s a professor of Biochemistry, I believe, in the East Coast, and really super sharp on circadian rhythms. And he kind of alerted me to this idea that time restricted feeding, the shortened feeding windows, seem to be quite beneficial for a variety of reasons.

But he made a really strong case for this idea that we would do better to eat more of the calories and more of the carbs earlier in the day. And I know there’s carb backloading. This becomes, again, if you want to get a contentious pissing match on the internet, just throw one of these concepts out there.

But Bill made a really interesting case that there’s an argument based off of circadian biology that we should eat more carbs, more calories earlier. And that is one thing that I’ve focused on.

So I will do, whereas before I might do an 18 hour fast, I’ll just do 14 and 16 hours now. And I will do a really robust meal, and then maybe 2 to 3 hours after that I have a Jiu-jitsu session. And then that meal ends up being much higher in carbohydrate. And I again kind of base it off the volume and intensity.

But then usually my dinner… I do two to three meals a day. Probably 80 percent of the days it’s three meals, 20 percent of the days it’s two meals, and that tends to be more the weekends when I’m just hanging out with family and I just want to be lazy and I don’t want to cook yet another meal for myself and all that.

I do partition closer to the pre-workout period but I’m not like taking a maltodextrine drink right before and one right after, and all that type of stuff. There might be some upside to that, but I have noticed for my digestion that the digestive process, for me, does much better with less frequent feedings, and less refined foods and all that type of stuff.

So I’ve had a pretty darn good degree of success with that so far. And I mean it is dead simple. I would be hard-pressed to think of a more simplistic way of eating and fueling. It is really, really simple.

But at 45 years old, I just got my purple belt last Saturday and I’m doing great on that. And body composition is good. My wife is still willing to sleep with me with the lights on most nights. So life’s pretty good in that regard.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Congrats, I saw that purple belt. It’s quite an achievement.

[Robb Wolf]: Thank you.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So is there anything we’ve missed that’s important about your most recent thinking on this subject?

[Robb Wolf]: No, I don’t think so. You did a great and thorough job asking this stuff.

Again, I would just encourage people to think about, if they feel off-put by this idea of Paleo diet type stuff, just give some thought to this. Is there any merit looking at biology and thinking about the evolutionary underpinnings, particularly when we see things go south?

If we don’t see health or other parameters that we would ideally like to have, if something significant is changed in that organism’s environment, do we have any insight from looking at what the environment preceding that event? So that’s kind of the totality of my greasy used-car salesman pitch on this stuff. Is there anything we can learn from that?

And it’s not just around food. It’s around sleep, and photoperiod, community, gut microbiome. All of these things really, when we see problems popping up, it’s this discordance model again. And modern medicine is shockingly well-suited for dealing with acute injuries and infections, and it has been an appalling failure with regards to chronic, degenerative disease.

And people may get their back up about that and say we work very hard. I don’t doubt that people do, but if you simply look at disease rates and incidence – Type II diabetes, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s – they’re increasing at exponential rates, yet we know more about the disease process than we’ve ever known in history.

Our iPhones, iPads and computers get cheaper and better every single year, and it’s because we properly apply the technology and knowledge that we have around that topic to improving the product and the outcome. We do not do that in health and medicine, and it’s because we do not start the story from this evolutionary biology perspective, and start having the conversation from there. Because if you do that, chasing symptoms no longer works, and filing people into these arbitrary buckets of disease or not-disease doesn’t really work anymore.

In the 1900s, the previous century, was the century of eradicating infectious disease, for the most part. This century is going to be about dealing with chronic, degenerative disease due to affluence. And it is not going to be solved by a pill or a potion. It’s not going to be solved by telling people to eat less and move more, everything in moderation. Because all of that completely ignores every element of our fundamental evolutionary biology.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thanks, so much for that roundup.

To learn more about this, they can go and get your book. That’s available at Amazon. There were some bonuses or stuff. Is there anything like that still available?

[Robb Wolf]: The bonuses might pop back up again, but most of that was for saying thank you for people who were early adopters on it. But we’ll see. Maybe a couple of months down the road we might pop the bonuses back up.

(0:51:39) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay, cool. Are there any other good books or presentations on this subject that you’d recommend?

[Robb Wolf]: Oh, man, if people are not following Chris Masterjohn, they’re really missing out. That guy is brilliant.

And he’s been doing a deep dive on kind of a series of different nutrients that you need to pay attention to. And he kicked the whole thing off, actually, with iron. Both the iron deficiency, anemia, stories and also the iron overload stories.

So he gets into the biochemistry and the pathophysiology of when things are right and wrong. And then he also starts off at whole food solutions and also makes supplement solutions, and man he is just doing brilliant work.

Who else is doing great work? The folks at Nourish Balance Thrive are doing phenomenal work. Marty Kendall over at Optimizing Nutrition. They’re just some brilliant people.

It’s funny a lot of them had an engineering background and either they got sick or spouse got sick, and then they got in and started looking at this stuff. And it’s interesting. They come in with no medical training biases, and after they start retro-engineering, literally, the disease process, they arrive at something that looks like kind of an appropriate carb, Paleoesque looking nutritional intervention with a focus on sleep and gut microbiome and all that.

I don’t know if that’s just confirmation bias, or really smart people applying their training to figuring out a process. But it certainly caters to my confirmation bias, so I tend to like that stuff.

(0:53:14) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Cool.

What are the best ways for people to connect with you, and learn more about you and what you’re up to? Twitter or Facebook?

[Robb Wolf]: The blog and podcast live over at Robbwolf.com. The bulk of my social media time I spend on Instagram these days. My handle there is @dasrobbwolf, and I answer just about every single question that is shot across the bow there. So I do the best job I can to stay on top of that.

(0:53:45) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Excellent.

Just a few more details maybe on our personal approach through using any tracking. I know we’ve already spoke about them, so just really to see if there’s anything else.

I was wondering if there’s anything you track yearly, or every six months, or anything like that that we haven’t already spoken about.

[Robb Wolf]: So, I do check-in on my lipoproteins, that LPIR score, or LDLP, LPPLA2. There’s kind of a suite of somewhat obscure lipoproteins which I keep an eye on about once a year.

And part of that is because at the end of my last book, I was pretty beat up from that. Then I went on a Discovery Channel reality show, called I, Caveman. And we had to live like Stone Age hunter-gatherers. We had stone tools, we lived at 8,500 feet in the Colorado Mountains while there was still snow on the ground.

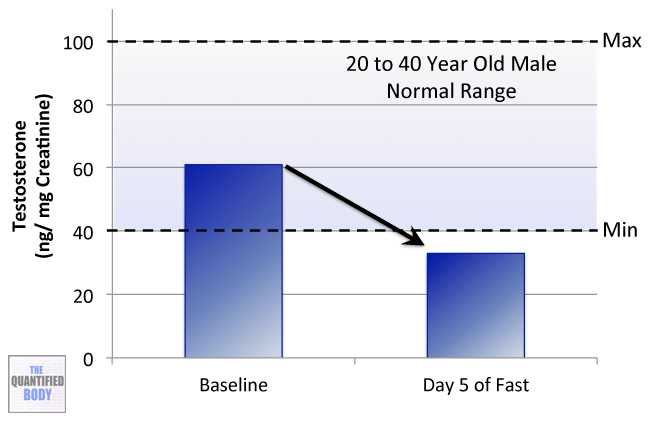

We basically starved for 10 days until I killed an elk with a hand-thrown spear, and that was the first food we ate. But the long and short of that is I lost 18 pounds in 10 days, and was super beat up. And I ended up with some HPTA axis dysregulation. My thyroid was super low, I had adrenal issues, testosterone was kind of tanked out.

And so an interesting sideline with that was that my lipoprotein numbers were sky-high. My LDLP was 2,800 or something like that. Really, really high. And the clinic that I’m on the Board of Directors of here, we do tons of lipidology work. And the doctors were freaking out, you need a statin. And I said no I don’t, I’ve got other stuff going on.

So we did some poking around, and I actually went on some Nature Throid, which is kind of like armor but a T3/T4 thyroid deal. And I did kind of a classic adrenal restoration story, high dose Vitamin C, some licorice, some adaptin. And I quit traveling, and I started really paying attention to my sleep.

And within three months I was off the thyroid medication, testosterone had more than doubled, both free and total. And I felt remarkably better after that, shockingly. And my lipoprotein number, my LDLP, had gone from 2,800 to, I want to say, 1,100. And eventually it settled out at 800 or 900.

I do check back in on that every once in a while though, because that combination of super low testosterone and disordered thyroid. The low circulating T3 that really down-regulates your LDL receptors in the liver. So you just don’t clear LDL particles, so they accumulate in circulation. And once they start accumulating, then the potential for them to oxidize is much greater.

And then I also potentially have a little bit of iron overload going on. So I had a really kind of nasty situation brewing there. So I do check in on that, just to make sure everything is bumping along good. So I do a really thorough thyroid assessment, which is TSH, T3, T4, reverse T3, thyroid uptake, and then some of the just kind of background iodine status. And that gives me a pretty good benchmark about where that is.

And then I’ll check testosterone, estrogen, estrodiol, DHT, to kind of see where that part of the hormonal axis is. Because again, based off inflammation, fatty acid ratios and what not, you can start pushing more testosterone towards the DHT pathway, which can be problematic for the prostate under certain circumstances.

So I pay attention to those things, but it’s usually about once a year. But again, I’m a lazy cuss when it comes to that stuff. I know some people test it like once a month. I’m more of a once a year, maybe once every six months on some things. But more of a once a year deal.

(0:57:58) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thanks for that, very, very interesting. And the fact that you recovered, and you obviously see that as an actionable metric that you can keep up with.

I’m just wondering, which labs were there? If there’s any specific place, or are these just standard Quests, or something like that?

[Robb Wolf]: We tend to go through LabCore because LabCore ended up purchasing LipoScience, which is the [unclear 58:09] that developed the NMR technology around looking at lipoproteins. There’s other ways of looking at it, and they have pluses and minuses to them, but in my opinion that NMR spectra that looks at the LPIR score and lipoprotein count is head and shoulders above everything else out there.

The guy that largely developed it, William Cromwell, he was a physical chemist, a believe a PhD, which is basically a physicist who studies chemistry. And then he went to medical school, and he got into this NMR spectra jockeying type stuff, and developed this whole technology around looking at these lipoproteins. They have some really interesting correlation studies that they’re doing.

There’s a biomolecule called glycA, and by looking at glycA in relationship to some other lipoprotein fractions, they’re claiming that they can see things like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and insulin resistance decades ahead. And they’re still awaiting FDA approval on that. But it’s really interesting. So I tend to really put some pretty heavy weight on that lipidology side with regards to that LPIR score and that whole NMA spectra technology.

(0:58:28) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Thanks very much, that’s very, very interesting stuff.

I think I know what you’re going to say here. If you were to recommend one experiment someone should try to improve their body health, performance, longevity, chronic health issues, whatever, with the biggest payoff, what would it be?

[Robb Wolf]: Sleep.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay.

[Robb Wolf]: Sleep. I mean, maybe a blood sugar deal I can make an argument for, but if we improve your sleep, there is nothing else that you could do that’s going to improve everything else more.

And the one caveat with that, if we have say a shift work population – police, military, firefighter, new parents, medical caregivers – who can’t control their sleep, then they really need to get a handle on the glycemic load of their diet and get it to a level that’s non-toxic for them.

But even then, the shift-workers, they need to pay even double attention to the sleep. When they do sleep, they need to sleep well. When there is sunlight, they need to get out into the sunlight at appropriate times. It becomes doubley important for them.

But the greatest return on investment anybody’s going to get on any of this health and wellness stuff is putting more emphasis on their sleep.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And should they just track hours slept, something simple like that?

[Robb Wolf]: Hours slept is good, but it’s more the ritualized process. When the sun goes down, then you dim the lights. And if you’re still on the computer, you flip on the f.lux, and you put on some Blue Blockers, and you set up a ritual.

To the degree that we set our lives up that we have to live and die by self-control, we’re mainly going to die. We’re going to fail. And so we have to set up a kind of a habituated process so it really takes the thinking out of it; it’s just what we do. So I would tend to focus more on that.

And then certainly if you want to keep an eye on approximate duration in bed, but that’s a whole other interesting feature too, is when you start paying an over the amount of attention to those things, then you start getting anxious about it. And I just see this damnable downward spiral in the quantified self space, where I just want to put a black bag over these people’s heads, drag them out into the woods and stick them in a tent.

And it’s like, there’s a creek full of fish. We’ve got them trapped behind a fish weir, you need to get them out by hand and gut them and cook them. Here’s the kit to make a fire. We don’t make it ridiculously hard, but you’re going to have to work to get your dinner, work to stay warm. And when the sun goes down you’re going to make a decision, do I want to sit up in the dark, feeding this fire on the limited firewood I have, or am I going to go crawl into my sleeping bag and go to bed.

They’re not quantifying a goddamn thing under those circumstances. And all of a sudden, all of the digestive issues disappear, and the sleep disturbances disappear, and they’re three body fat percentage point is lower after a week and it’s not because they’re hypocaloric, it’s just because they’re not inflamed and insulin resistant.

And so again, I try to get people to just live. I’ve really been harping on this thing of track what matters. And the longer that time goes along, I’m just finding fewer and fewer things that matter, relative to the experiential process. Be in your body, experience what is going on. Be in contact with what your emotions are, and develop a little bit of a zen and stoic process, where you can see these things occurring, and then you can choose to how you respond to it.