Life extension – this is something I’ve wanted to spend time on for a while.

In this episode, I interview 5 thought leaders from the life extension movement. Consider this an introduction to the current status of life extension tools and technologies, as we look at most areas with a broad first-look.

You will learn where things are and what the risk profile of those life extension tools and technologies is today.

All interviews took place at RAADfest in San Diego. This is one of the larger life extension technology conferences today. It stands for Revolution Against Aging And Death and then fest for the festival.

I would encourage you to skip around this episode. It’s long, and there might be a specific topic that you’re interested in. So check out the notes below and pick the area that you’re most interested in first and start there. If you get through the whole thing it will give you an overview of where things are currently at.

“At the moment we’ve got this burgeoning of the rejuvenation technology industry with more and more investors realizing that this is the next big thing”

-Aubrey de Grey, PhD

“Our life is code and I think that we can modify that. First, we’ll look for human health and then we’ll look to enhance your life for where you want to live, who you want to be and what you want to achieve.”

-Liz Parrish, CEO of BioViva

“Basically what we’re trying to do is reproduce the young physiology that you had when you were younger [by replacing your old plasma with younger plasma]”

-Dr. Howard Chipman

“It’s not entirely crazy to think that some point soon, we can turn some of these senescent cells back into healthy cells.”

-Brian M. Delaney

“Not all biohackers would call themselves quantifiers. […] In the quantification side, well instead of taking 20 things, if there are two or three I can do that I get 90% of the benefit from, I’ll do that. That’s efficiency.”

-Bob Troia, “Quantified Bob”

The episode highlights, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

What You’ll Learn

- Start of the first interview at RAADfest with Aubrey de Grey. Presentation of SENS Research Foundation. (9:32).

- The actual state of SENS Research Foundation. (12:22)

- Therapies to target the seven types of aging damage. Some of the diseases linked to them. (14:18)

- Companies associated with SENS and the variety of startups that have sprouted from it. (16:57)

- Aubrey’s particular views and interests in life extension. (28:10)

- Start of Liz Parrish’s section and the introduction of BioViva. (33:50)

- The new focus of BioViva, using a meta-analysis of public data to find promising drugs and genes (38:30)

- The scale and patients of BioViva’s potential gene therapy treatments. (41:30)

- The biomarkers Liz and her group work with, where they come from and how they are detected. (44:00)

- The process of receiving a specific gene therapy (1.0 vs 2.0 human) (46:00)

- Self-experimentation, data collection and associated biomarkers (48:41)

- What drove Liz Parrish to investigate riskier and more experimental medical areas. Her initial experiences in the area. (53:00)

- The process and the legal loopholes that were necessary for Liz to be treated with gene therapy (56:00)

- The current treatments and products BioViva offers. Future prospects for genomic counseling, new genes, and methylation testing. (59:48)

- Ending of the interview and Liz’s conclusion on the potential of gene therapy (1:00:50)

- Start of the interview with Howard Chipman, from Young Plasma (1:02:15)

- The basis and origin of the Young Plasma Project. (1:05:08)

- The positive and negative effects of using Young Plasma and the protocols associated. (1:07:21)

- The Ambrosia study and the biomarkers that are generally used in Young Plasma (1:08:30)

- The cost associated with participating in Young plasma and the mechanisms of the process. (1:11:34)

- Howard’s own experiences in the area and ending (1:13;40)

- Start of the interview with Brian M. Delaney. His experience with Young Plasma. (1:18:20)

- The introduction of Brian M. Delaney and his work in the LEF (Life Extension Foundation) (1:22:37)

- The repurposing of old drugs for new anti-aging purposes and new treatments and research. (1:24:20)

- Brian’s objectives in LEF and life extension (1:30:00)

- How Brian got involved in the area of life extension. (1:32:43)

- The current state of Brian’s research. (1:36:00)

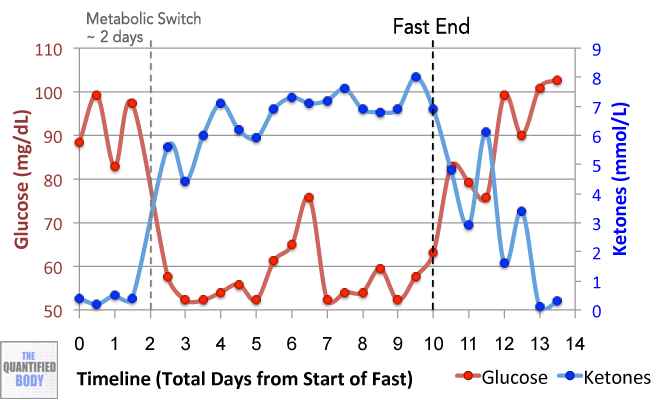

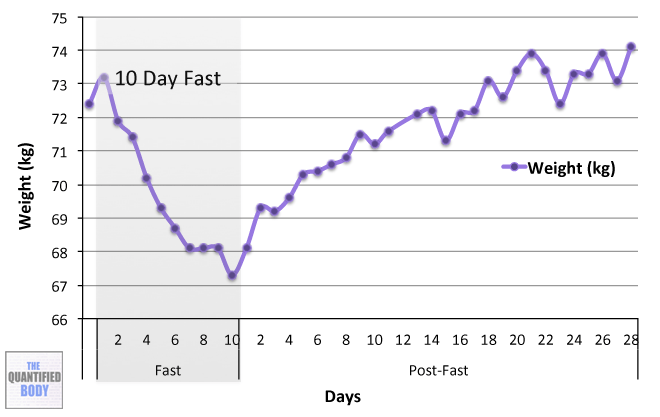

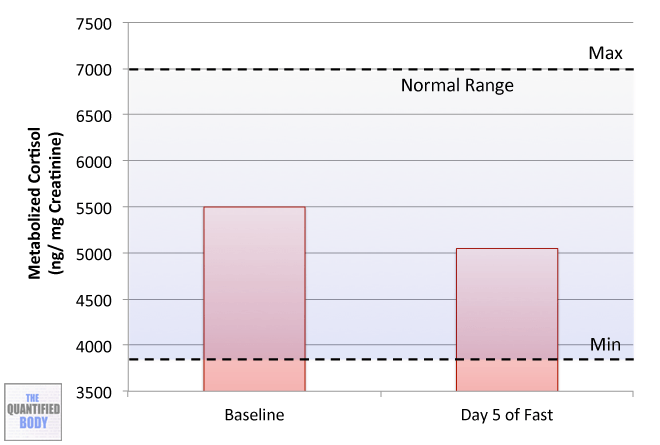

- Brian’s health, tests, and biomarkers. His experiences with Calorie Restriction. (1:41.10)

- Further experiences of Brian with CR, insomnia and other physiological parameters. (1:51:10)

- Brian’s experience with Rapamycin, nicotinamide riboside. (2:02:01)

- Brian’s experience with Metformin and senolytics. (Dasatinib and Quercetin). (2:08:32)

- The effects of senescent cells in our body and the off-target effects of senolytics. Senomorphics. (2:13:59)

- The DNA methylation testing at Zymo Research Program. (2:19:39)

- End of the interview with Brian M. Delaney. (2:23:34)

- Start of the interview with Bob Troia (Quantified Bob). Presentation and opinion of RAADfest. (2:24:44)

- Bob’s activities, tracking during the last few years. Recent changes in the landscape of life extension. (2:28:39)

- Which consistent data in Bob now regularly collecting about himself. (2:38:12)

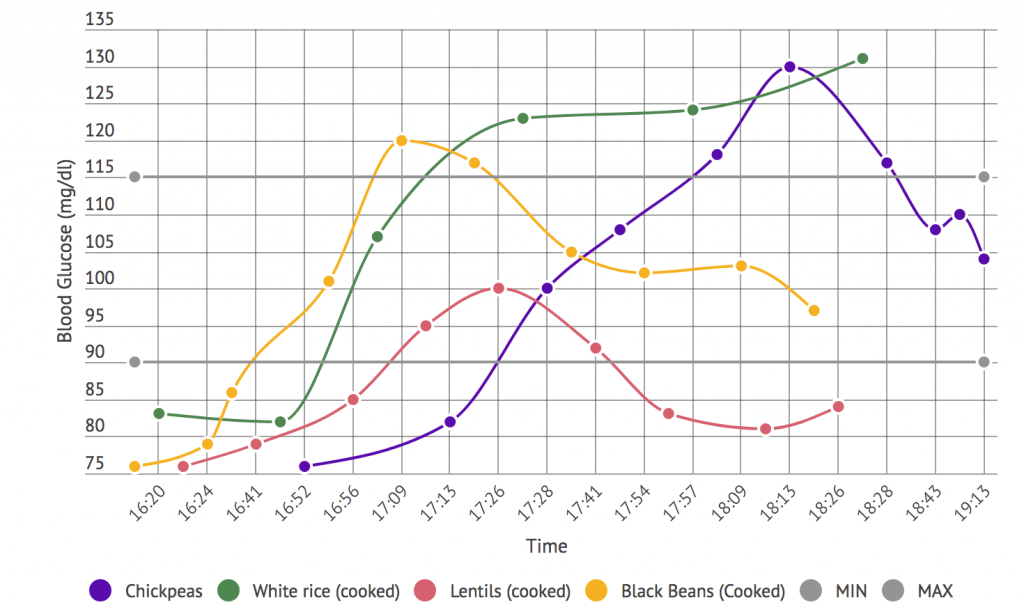

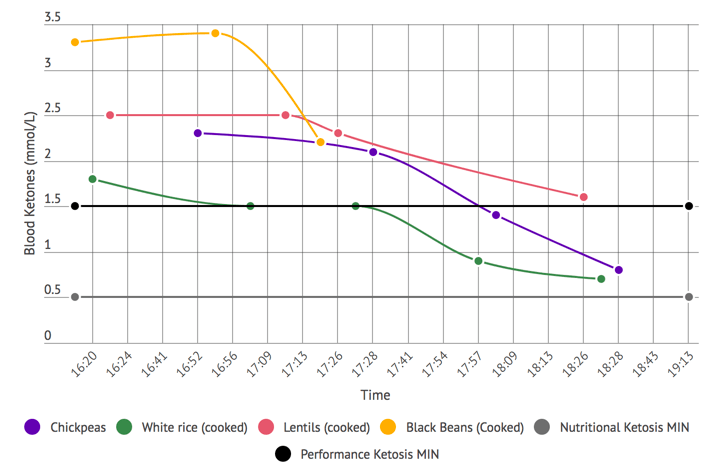

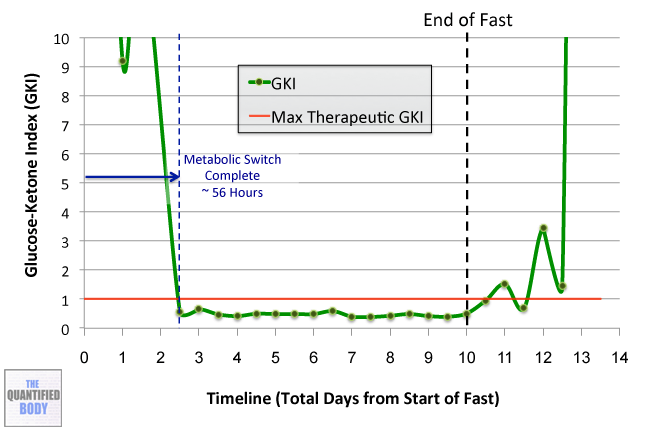

- Ketone testing and Bob’s experience with KetoneAid. (2:40:11)

- Recent advancements and curiosities in the area of life extension and supplementation. (02:46:57)

- End of the interview with Bob Troia. Invitation to contact him through social media and his web. (2:50:10)

- Damien’s conclusion and some questions to take home about the main themes of the podcast. (2:51:13)

Thank the interviewees on Twitter for the information they shared and let them know you enjoyed the show.

Thank them here: Raadfest (the conference), Aubrey de Grey, Liz Parrish, Brian M. Delaney and Bob Troia (Quantified Bob).

Interviewees in Order of Appearance

Aubrey de Grey, PhD

- Background: Aubrey is the de facto founder and head of the movement for life extension. He began working on in the 1990s. He is the head of SENS Research Foundation(SENS = Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence). Aubrey was previously interviewed in Quantified Body episode 14.

- Books: The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging (1999) (Dr. de Grey’s first book on the subject of his Ph.D.).Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs That Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime (2008). This last one provides a good primer/framework on the 7 areas of aging damage research.

- Research: Dr. de Grey’s research journal is Rejuvenation Research. For a comprehensive list of his research see Aubrey de Grey’s PubMed. A key paper is Strategies for engineered negligible senescence. It describes the strategies for engineered negligible senescence (SENS). It expands on the concept and provides the background to all his work.

Liz Parrish

- Background: Parrish is the CEO of BioViva, an advanced life extension center. It aims to develop new gene therapy based health testing and analysis techniques for the betterment of your health. They offer help navigating the details of genetics and family history. They can also assess how they impact your health and well-being.

- Self-experimentation: She was the first person to undergo gene therapy. In particular, one targeting life extension. This took place three years ago. She’s known as patient zero in some circles for this reason. Check Liz’s journey as a test subject of gene therapy here.

- Research: As CEO of BioViva, she recently presented the results from her telomere lab. Telomeres are DNA pieces we can look into to assess aging.

- Follow Parrish on Twitter.

Dr. Howard Chipman

- Background: Dr. Chipman is the medical director at Atlantis Clinic. He oversees the Young Plasma section. Their approach is to transfuse all the regenerative and healing factors present in young blood. This is done by transfusing the plasma (blood minus the cells) of young donors into an older patient. This was first tested in the 1920s in Russia. He is also involved in Aurora Aerospace. It is a space training company for jet fighters and zero-gravity flights.

- Research and experience: He specializes in emergency medicine. He has treated patients with life-threatening conditions. These include heart attack, drug overdose, shock, or massive bleeding. You can check Dr. Chipman’s Pubmed articles here.

- Find Dr. Chipman on Facebook.

Brian M. Delaney

- Background: Brian is an advisor for the Life Extension Foundation. LEF is a nonprofit organization. Their long-range goal is to extend the healthy human lifespan. This will be done by discovering scientific methods to control aging. They have been proficient in the supplements area. They have produced many well formulated and effective supplements. Before his involvement in the LEF, he was a philosopher and translator. He is based in Stockholm, Sweden. He is also a founding member of theCalorie Restriction Society.

- Books: The Longevity Diet is Mr. Delaney’s most popular book. In here he and Lisa Walford explain in practical terms the concept of calorie restriction. They consider CR “a life-extending eating strategy with profound and sustained beneficial effects”.

Bob Troia (Quantified Bob)

- Background: Bob appeared in episode 22 way back in the Quantified Body. He quantifies a lot of n=1 experiments and publishes them on his blog.

- You can find him on Twitter.

Tools & Tactics

Interventions

- Stem cell treatments to combat cell loss. Stem cells are undifferentiated cells capable of generating many different cell types. They substitute the ones lost through aging1.

- Mitochondrial mutation treatments to combat aging. Still in the early stages. Mitochondria are cellular organelles responsible for energy production. The accumulation of mutations throughout life can impair them. It can even stop their correct functioning. The reversal of these mutations might partially stop the aging process.

- Telomerase induction therapy. Telomeres, the protective ends of linear chromosomes, shorten throughout an individual’s lifetime. Telomere shortening is a hallmark of molecular aging. It is associated with the appearance of age-related diseases. Several scientific articles, including María Blasco‘s 2 have been recently published. They suggest that telomere growth can reduce the phenotypes of aging.

- Myostatin inhibition therapy. The inhibition of this protein can increase muscle mass and strength. These results apply to mice3 and possibly in humans. It is believed that it could be successfully employed in cases of muscular dystrophy.

- Intravenous fluid therapy. Intravenous fluid therapy. It is the introduction of a fluid (plasma, serum, antibiotics) in the vein of a patient. It is generally for employed for purely medical purposes. In the case of Young Plasma, it is the method used to introduce the plasma in the patient’s system.

Tech & Devices

- 10,000 Lux Lamp: Lamp that replicates strong sunlight. Damien has been using this in the morning to reset the circadian rhythm. this has the result of improving sleep quality. These lamps are designed for use by people with Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). They provide sunlight in dark months of the year.

Supplements & Drugs

Drugs (Typically More Potent/ Require Prescription)

- Senolytics: They are small molecules capable of inducing the death of senescent cells. They are still under research. Senescent cells are non-functional ones. Dasatinib is a compound generally used in cases of leukemia. As of late, experts think it can be repurposed as a Senolytic along with Quercetin. Brian mentions taking 5.0mg of Dasatinib and 50 of Quercetin per kg of body weight.

- Metformin: A drug used to improve blood sugar regulation in diabetes. Researchers are looking at its wider applications with cancer treatment. It can inhibit insulin secretion. Brian mentions taking up to 500mg.

- Statins: They are lipid-lowering medications. They can reduce illness and mortality in those who are at risk of cardiovascular disease.

Supplements

- Rapamycin: A compound that has been researched for its life extension properties. According to Brian, it is potentially senomorphic (capable of restoring senescent cells). It is believed to work by stopping certain responses to nutrients that can accelerate aging.

- Nicotinamide riboside: Brian mentions that it is useful for raising NAD+ levels. This happens in particular in the blood and in the cells. NAD+ is used in many redox reactions, including the ones needed to get energy. Brian mentions taking up to 500mg daily at some points of his fasting cycle.

- Nootropics: They are drugs, supplements, and other substances. They might improve cognitive function in healthy individuals. In particular, they may improve executive functions, memory, creativity, or motivation4.

- KetoneAid: It is a series of ketone esters (beta-hydroxybutyrate). They possess a great energetic performance. Generally used by elite athletes to achieve great bursts of power.

- Ketosports KetoForce: KetoForce contains the endogenous ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB). It is in sodium and potassium salt form. The compound BHB can be used as an energy source by the brain when blood glucose is low. Ingesting KetoForce raises the levels of blood ketones for 2.5-3.0 hours after ingestion. (Note: A similar product from the same company is Ketosports KetoCaNa). Damien expresses his preference for KetoCaNA.

Tracking

Biomarkers

Inflammation Markers

- High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP): Elevated hs-CRP levels show inflammation. That is damaging to inner artery walls. If your level is below 1 mg/L then you do not have a cardiovascular disease risk. Liz mentions this as an example of a classical biomarker.

- Homocysteine: High levels can be predictive of increased risk of inflammation of blood vessels. Low levels are generally not indicative of anything in particular. Anything over 150 μg/dL is generally considered an elevated concentration.

Blood Sugar Regulation Markers

- Fasting Glucose Levels: A biomarker used to understand blood sugar regulation. Optimum levels are between 70 and 90 mg/dL. Higher ones show some level of blood sugar dysregulation. That lack of regulation increases the risk for diabetes II. Liz mentions this again as a classical biomarker.

Cholesterol Based

- Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL): The traditional measure of ‘bad cholesterol’. That is the type that causes heart disease. Less than 100 mg/dL is considered an optimal level. Levels between 160-189 mg/dL increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Research has shown that LDL alone is not the best predictor for cardiovascular risk. LDL particles with the smallest sizes are most damaging to the cardiovascular system. Still, as Liz says, people with high LDL might never have a heart attack.

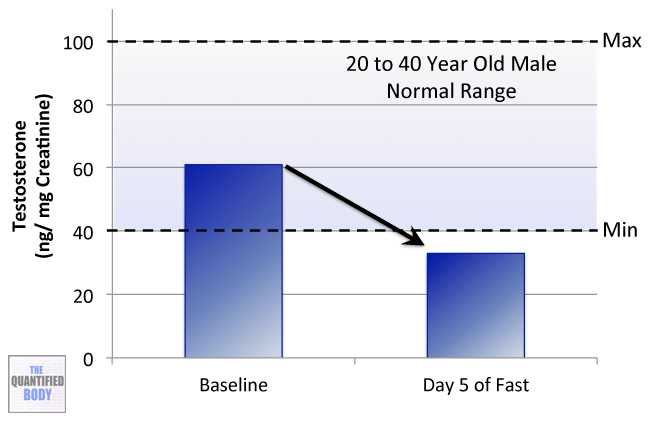

- Testosterone: It is the primary male sex hormone and an anabolic steroid. Testosterone is used as a medication in several cases. Some of them are low testosterone levels in men and breast cancer in women. Normal levels are between 264 to 916 ng/dL from 19 to 39 years old males, and they decline after that.

Associated to neurodegenerative diseases

- Amyloids: Amyloids are proteins that can arrange into fibers and plaques in the brain. They give origin to diseases like Alzheimer’s. The presence of visible aggregations has been associated with the origin of the disease. Still, recent studies might show that it is not the plaques that are responsible. Individual free proteins might cause the disease. Several complex methods that use specific ligands are used to detect them5.

Associated to cancer

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): It is a set of proteins that are mainly present during the fetal stages of development. This is why their presence in normal blood is usually very low (about 20 ng/mL). Still, these levels increase in some types of cancer, which is why it is used as a tumor biomarker.

Lab Tests, Devices and Apps

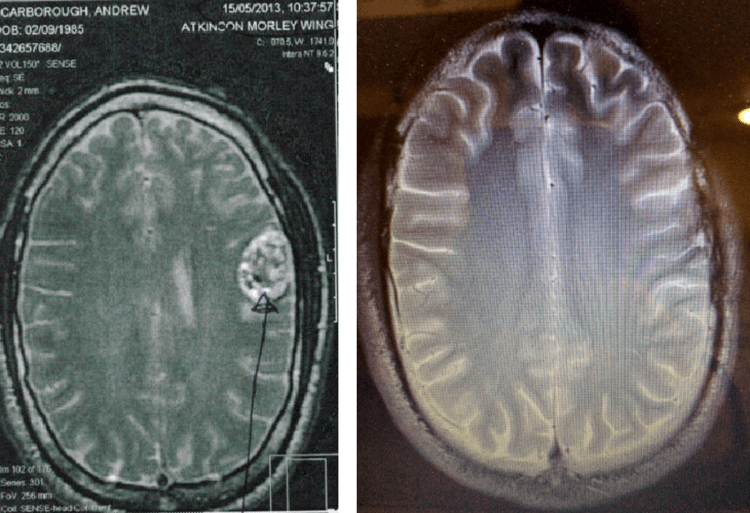

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Mainly used to provide information on the inner workings of the body. Liz used MRI throughout her gene therapy to view any changes in muscle mass and white fat.

- Telomere length testing: Telomere shortening is associated with many health conditions. These lengths can be altered in response to social and environmental exposures. These two discoveries have underscored the need for methods to quantify telomere length. Terminal restriction fragmentation is one of the main methods used as of now for this purpose6.

- Methylation testing: Methylation is a series of modifications that your DNA can be subject to. They play an important role in many chronic diseases. Through tests you can more effectively understand the diseases you might develop. BioViva aims to include this test to their list. This will enhance its predictive capabilities.

- Ketone testing: The different approaches to measuring ketones provide different perspectives on your ketone metabolism. These can be looked at as the ‘window of snapshot’ that they represent. Some methods have a snapshot of a longer duration. These provide more of an average reading. Others might provide a direct status of that exact moment. Moving from the more average-based value end of the scale to the more direct status end you have:

- Measuring ketones via the urine (via the ketone body acetoacetate). They have the longest snapshot with it representing your ketone values over the last 5 to 6 hours.

- Measuring via the breath (the ketone body acetone). It has a smaller snapshot window of the 2 hours leading up to the measurement.

- Measuring via the blood (via the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate). It provides you a snapshot of your ketone level at that exact moment.

The various devices available for glucose/ ketones testing and mentioned include:

- Urine Ketone Strips: Several parameters can interfere with the measurement values provided. They include both hydration status and becoming keto-adapted. They are the cheapest and starting with them is recommended.

- Ketonix Breath Meter: Currently the only breath acetone meter. If you are moderate to high on this meter you are in ketosis (i.e. typically over 0.5 mmol/L). This device is recommended in epilepsy cases.

Other People, Books & Resources

People

- William Faloon: The actual president of the Life Extension Foundation. Check his twitter here.

- Dean Ornish: An American physician and researcher. He is the president and founder of the nonprofit PMRI. That stands for Preventive Medicine Research Institute in Sausalito, California. You can check his website here.

- James Clement: The founder of Betterhumans, a transhumanist bio-medical research organization. They run open-label, non-randomized simple controlled trials

Organizations

- SENS Research Foundation: Foundation for the research of “Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence”. Founded by Dr. de Grey as an offshoot of The Methuselah Foundation. They work to develop, promote, and ensure widespread access to therapies. In particular, those that cure and prevent the diseases and disabilities of aging. This is done by repairing the damage that builds up in our bodies over time.

- Ichor therapeutics: It is a vertically integrated pre-clinical contract research organization. They focus on the study of aging and aging pathways. It was set up to work on macular degeneration, which is the number one cause of blindness in the elderly.

- Covalent Bioscience: It sprouted out of the work that SENS funded on amyloidosis. Amyloidosis involves waste products accumulating outside of the cell especially in the heart. They aim to develop and create affordable, better antibodies and vaccines. These will aim to solve a range of unmet medical needs.

- Unity Biotechnology: Flagship company in the area of removal of senescent cells. Their mission is to extend human healthspan, the period in one’s life unburdened by the disease of aging.

- Juvenescence: It is a drug development and artificial intelligence company. It focusses on aging and age-related diseases. It was created by Jim Mellon and his colleague Greg Bailey. Juvenescence AI combines advances in artificial intelligence with classical development expertise.

- Andreeseen Horowitz: It is a venture capital firm in Silicon Valley, California. It backs bold entrepreneurs building the future through technology.

- Y Combinator: It is an American seed accelerator, started in March 2005. They select and fund startups with great potential to allow them to grow as fast as possible.

- BioAge: A company started by Christian Foley. It focuses on using a unique computational platform that explores a universe of proprietary and public data. The main aim is to identify and target molecular factors that influence longevity. Their target is to slow and stop aging.

- Insilico Medicine: A company run by Alex Zhavoronkov. It specializes in the field of deep learning for drug discovery. It is also invested in personalized healthcare, and anti-aging interventions.

- Integrated health systems (IHS): A company focused on advancing the healthcare industry. They do this through the latest Gene Therapy techniques used in longevity research. By pulling from public sets of biomarkers they aim to select some to identify patients. These patients will then receive the gene therapy treatments.

- SpectraCell: A group of laboratories specializing in personalized disease prevention and management solutions. They were used by Liz Perrish for the MRI imaging and the telomere length testing.

Resource Links

Here are the links to each individual interview on our facebook page. On top of that, there are other interviews that weren’t included in the podcast:

- Aubrey de Grey

- Liz Parrish

- Howard Chipman

- Brian M. Delaney

- Quantified Bob

- David Wood: Chair of London futurists. Author of Sustainable Superabundance.

- “Reason”: Founding member of Repair Biotechnologies.

- David Bowman

- Mariana de Chellis: Member of Outreach. Check her Instagram here.

- María Entraigues-Abramson: Founder of Longevity bridge. She is also the Global Outreach Coordinator for the SENS Research Foundation.

Full Interview Transcript

You may know that that’s been a personal interest of mine for quite a while. This podcast is basically looking at topics of life extension, longevity, performance and general wellness and how we can quantify and ensure that we’re getting those types of results.

So this is something I’ve wanted to spend some time on for a while and you could look at this as an introduction to the current status of life extension tools and technologies and where things are and what you could do an experiment with today and what the risk profile of those tools and technologies could be today. Or actually the potential quantified benefits, if any.

So this is a test episode because basically it’s based on some live videos that I recorded with people attending RAADfest 2018 which was held in October in San Diego. RAADfest is one of the larger life extension technology conferences today. RAADfest stands for Revolution Against Aging And Death and then fest for festival.

So pretty much everyone who is active in this new industry, companies like Life Extension Foundation, the hosts and the leaders of this conference, Coalition for Radical Life Extension, investors, biotechnology startups in this new industry which is called Rejuvenation Biotechnology. That’s the name it’s starting to get for itself. All of these people were here at this conference so you’ll see there are a number of different profiles that I interviewed and that you can find in this interview.

So I think it’s a good episode to get an introduction into these topics to start understanding where life extension is and start getting an idea of where you may want to look into more and learn more about one of these topics. If you want to go check out the live videos, those are all on the Facebook page. So you can go to Facebook and just search the Quantified Body and you’ll find all of these interviews in the live videos there.

I would encourage you to skip around this episode. It’s long, as I said. So if there’s a specific topic that you’re interested in, you may want to check out thequantifiedbody.net blog and check out as always, we have the highlights, the times, who’s talking about what subject at what time in the episode so you may want to just jump to one hour or two hours in. Pick the area that you’re most interested in first. However, going through the whole thing will give you an overview of where things are at.

So with that, just let me give you some brief introduction into the topics and the people who are going to appear in this episode.

The first one is Aubrey de Grey from SENS Research Foundation. I interviewed him in episode 14 of The Quantified Body podcast. Really in this episode, he gives us an update on how life extension has moved from the fringe, basically something that was looked at as a fringe science, to becoming a new biotechnology industry where you know have a lot of funding coming in and a lot of startups becoming active.

As I said before, this is now starting to become labeled, rejuvenation biotechnology. I just went to another conference on this in London just a few weeks ago where there were a lot of prominent people and investors. So you can really see that this is growing into an industry all of itself more credible. So that was a good discussion on the progress of the tools and the funding and everything that’s going to bring it alive and make it happen in the longer term.

The next person I interviewed here was Liz Parrish from BioViva. Liz runs a biotechnology company focused on life extension and she was the first person to undergo gene therapy targeting life extension and this took place three years ago. She’s known as patient zero in some circles for this reason. She just presented the results from her telomere lab. Telomeres are something that people are looking at to measure how we age.

The idea is that telomeres get shorter as we age so you can have an idea of someone’s biological age based on measuring the length of your telomeres. So hers were actually shorter than average when she first tested before her gene therapy and now they are longer than average three years down the line using the same test from SpectraCell Labs to measure that. So with Liz, we talked about plans for her company to support the development of life extension therapies and of course her own experience with gene therapy to extend life.

The next person we have on the show is Reason from Repair Biotechnologies. So this is one of the new biotechnology companies that has emerged and been funded in this area already and they’re working on life extending therapies. He’s also the author of the blog Fight Aging which has been around for a really long time.

I’ve known about this blog for a very long time and he’s constantly been covering the science, the updates and how things are progressing; the ideas, tools and so on. So it was interesting to talk with him about his own self-experiments with senolytics, which you’ll learn about is probably the newer term tools that people will be using to aim to extend or rejuvenate themselves and also just an overview of where he’s focused and the science he has covered and some of the more interesting things.

The next person is the episode is Brian M. Delaney from Life Extension Foundation. So Life Extension Foundation, you may know of, is a company that has been very active in the supplements area and they tend to have better formulated supplements than the average company and they’ve always written pretty good articles with in depth references and citations. So Brian is sort of chief guinea pig for the life extension which is his new role he has taken on. He has been an advocate and someone who has practiced caloric restriction for a long time.

So we talked a little bit about that and then we talked about his new job with Life Extension Foundation and the things and the tools he has been testing which include senolytics and Rapamycin; two potentially newer term tools that can be used for longevity purposes to try and extend your life. Also go into depth in both of those and his own experiments on what he has been up to.

Next person on the show is Quantified Bob, Bob Troia. So Bob appeared in episode 22 way back in the Quantified Body. He does a lot of n=1 experiments and he quantifies those so obviously he’s a good fit for this podcast so you might want to go back and check that. Basically, we had a chat about what he found interesting at the RAADfest, which of the life extension topics he’s most interested in and also his other recent quantified experiments that he has done since we last spoke to him.

And finally, the last person in this episode is Howard Chipman from Young Plasma. Now Young Plasma is providing transfusions today of young blood so blood from young adults to people who are older in order for them to benefit from rejuvenating properties. This was first tested in the 1920s in Russia in fact.

Since then, there have been mice experiments and there has also been some allozymes as human studies which have shown benefits from basically just transfusing younger blood into people with older blood. So he talks about that service, he talks about the latest study , Ambrosia, and how he got involved with it and what patients are doing and who’s using this currently. So that’s obviously interesting therapy right there also.

As per usual, there are extensive show notes for this episode. They may be more useful than usual. There’s links to everything mentioned in the show including the studies and easy listed takeaways. There are summaries of the biomarkers, the tracking, the tools and the tactics we discussed in this longer episode.

So please reference those especially if you’re not sure about anything. I know some of the topics get a little bit deep in this episode because some of the topics like senescent cells are actually complex. So I think you might find some of the show notes useful to get up to speed there.

Also if you want to receive in future, updates on episodes and so on, go to thequantifiedbody.net forward slash newsletter and from then on and henceforth, you will get an email from me in your inbox whenever a new episode comes out with all of the details of that episode. So you won’t even have to go to the blog.

That’s it for me. I’m now going to leave you to delve into these episodes and get a broad introduction into the topic of life extension.

[MAIN INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT]

(00:09:32) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: There we go. We’re live again. We’re at RAADfest again and we have Aubrey de Grey sitting next to us which is fantastic. If you’ve been watching the podcast, you’ll probably know that we spoke to Aubrey de Grey in episode 14 which was about three years ago I think. So we’re not going to go over all of that stuff. If you want to get up to speed on the basics and what he’s doing, check that out later and then you can come back to this. That’s probably the best way to go about it.

We want to talk about what’s going on now, what you’ve been achieving and then how it’s all going. So first of all, we didn’t talk a lot about the SENS Research Foundation; how it’s structured and basically what the mission is and how it’s structured to achieve that. So I thought that would be a good place to start.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Yes it is. If you [check 10:12], first of all, just generically, but also because that has been changing over the past couple of years. So we are based in California and we’re a charity. We’re a 501c3 as it’s called in the U.S. and that means that people can give us money with tax advantages. We also incidentally have an affiliate charity in the U.K. so that U.K. taxpayers, ID taxpayers from most of Europe can do the same.

But our goal is not only to get work done internally on the basis of money given to us, but also to be the engine room of the industry. Of course you might think well what is this industry? There has been this thing called the Anti-Aging Industry for quite some time, but it doesn’t have a very good repute. That’s no surprise because it’s fundamentally based on things that don’t work or hardly work. We are creating. We’re the new industry; the Rejuvenation Biotechnology industry [unclear 11:05].

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: You renamed it.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Things that do work. That’s right. Now that has really only happened over the past couple of years. There have been investors coming to us saying, “What can I do? How can I get involved in this? But I don’t like giving money away so please give me an investment opportunity.” Historically, we would not have been able to help them because the projects that we were working on were too early a stage for us to be able to make a case that really joined the dots all the way to eventual profitability.

That is no longer the case. We’re now up to about half a dozen projects that we gestated for, in some cases several years, and that we eventually were able to spin out and to start up companies and every one of those companies is doing pretty well in terms of bringing in money. In some cases, money that is the equivalent of multiple years of our entire annual budget.

The foundation is still very small. We only survive on something like five million dollars per year. Some of these companies are getting twenty or more and that’s fantastic because it means the science can get done faster. It’s also fantastic in the sense that we can focus on the projects that are lagging behind and still have not reached the point where they can be spun out and made interesting to investors.

(00:12:22) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So is that transformed over the last three years?

[Aubrey de Grey]: Really, yes. Until, I’m going to say four years ago, we had never done this. Not only we had never done it, but at the moment we’re in a position where we’ve spun out six companies I believe now, but actually we’re also working closely with at least a dozen or more other companies.

They’re not spin-outs, but they’re doing very closely aligned work and the people are very much looking to me and the foundation as source of introductions to investors for example. So for me personally, it’s extremely gratifying. I’m able to maintain this position of influence in the emerging industry that I historically had in the non-profit world.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So this is fantastic. So you listed several companies, the twelve companies that you spun out yesterday and also the SENS aligned. How many are there in total now that you consider within the right parameters?

[Aubrey de Grey]: Yeah. It’s a continuum. It depends how much [unclear 13:19] but at least a couple of dozen.

(00:13:22) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow. Wow. We’ll get into some of the specifics of that. So one of the things I wanted to talk about is when you published your book. Was that 2008? The first year?

[Aubrey de Grey]: 2007.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: 2007 and you published the seven types of damage of aging?

[Aubrey de Grey]: That’s right. I had been talking about that for at least five years before that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. Last night, you said that basically that hasn’t changed. That model has withstood time.

[Aubrey de Grey]: It has withstood the test of time, that’s right. Always though was the risk that there could be some new type of damage that had not been discovered.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Of course there still might be, but every year that goes by when it’s not discovered is increasing circumstantial evidence that it’s never going to be.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Similarly with regards to therapies, it’s very important also to recognize that we have not had any bad news of the form of this or that approach that we thought we would be able to take to succeed in repairing this particular type of damage is not going to work for some reason.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s not dead end.

[Aubrey de Grey]: That has not happened either.

(00:14:18) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Excellent. Excellent. Ok so if you got these seven areas, where are we making progress with this portfolio of companies now? Are there specific areas where we’re making progress now?

[Aubrey de Grey]: So that’s a much better finding. Really all of them, the progress is really encouraging; much faster than it used to be. So there is a possible big spectrum in terms of how far along they are. In fact, there has always been that spectrum.

So one of the areas is stem cell therapy to repair cell loss; cells dying and not being able to be magically replaced by cell division. That’s an area which was already sufficently established when we began a decade ago, but we have always deprioritized it with just an occasional little thing in the stem cell area. But other people with good money and from other sources are doing it so that’s [check 15:04] there. But pretty much all the other areas we have worked in, we have done quite a lot and yes they’ve all moved forward.

So the only one that is entirely within the foundation still is mitochondrial mutation. Even there, it’s probably not going to be all that long before we can [check 15:23]. Because after maybe ten years of working on it without anything really to show for it even before we were publication, we started making breakthroughs. We had our first real groundbreaking breakthrough publication two years ago now and we’ve made massive progress since then. We are universally recognized in the field as the world leaders in that area now and we believe that it’s going to be ready for private sector prime time fairly soon.

Now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we can shut up shop and declare victory at the foundation. Because first of all, we are obviously doing other stuff in addition the research. We have this very vibrant education arm and also we do regular outreach. But also, even though some examples within these seven things are already out there in the private sector, it’s been out, nevertheless there are other examples that still need to be gestated for a bit longer before they can really be of any proposition.

(00:16:16) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So some aspects of that damage hasn’t been spun out yet. So you said some of the mitochondrial mutations are looked at internally. When you’re saying internally, does that mean that you’re funding internal research or you’re funding external researches that you think are appropriate, but it’s internally funded?

[Aubrey de Grey]: In that case, it’s actually literally internal. We do the work in our own facility in Mountain View, California. We have a couple of other projects in Mountain View, but most of our work I think will be [check 16:44] about two-thirds is funded extramurally. In other words, we support professors in laboratories and institutes and universities.

(00:16:52) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow. Ok, cool. Ok so if we look at the timeline, this is the kind of stuff people are going to be really interested in. If we look at the timeline of where these companies are and where you think they’re going to get to some commercial or even clinical trials or something that people could actually get involved in, could you paint a rough picture or maybe something we can expect?

[Aubrey de Grey]: Sure, absolutely. Absolutely. So let’s take Ichor. I would say out of all the actual spin-outs that we’ve had, that’s probably the poster child in the sense that it’s the one that has attracted the most funding so far and it has also grown in terms of the diversity of things it works on. Ichor was set up to work on macular degeneration which is the number one cause of blindness in the elderly. It’s an example of what we call LysoSENS. It’s caused by the accumulation of waste products inside the cell in a particular part of the cell called the lysosome.

We developed a method to fix that in house in our Mountain View facility. For several years, we couldn’t quite get there. We ran into the sand for a long time and we were a bit frustrated and one of our employees decided that he wanted to run with it. He felt he had a solution to this last problem. He was right it turns out [check 18:02]. He formed his company; fine with us.

We only took a very small nominal percentage of the company in return for the intellectual property. The technology went forward, they’ve got good money and there and then, they’ll be doing clinical trials next year or possibly even by the end of this year. That’s just one example.

Another company Covalent Bioscience which is in Texas. It’s a company formed out of the work that we funded on amyloidosis which involves waste products accumulating outside of the cell especially in the heart. It’s a very important phenomenon in terms of mortality and the [check 18:38]. That went well enough that the two main academics who were spearheading that work have now quit and gone full-time with the spin-out company. They are again hoping to be in clinical trials in the very foreseeable future so it’s happening.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. It’s starting to get to meet the road. Which do you think is going to be, I guess it’s the mitochondrial mutation which is going to be the last thing.

[Aubrey de Grey]: I don’t like to say. At this point, I would say the mitochondrial mutation strand is probably moving as fast as for example, the extracelular crosslinking strand; the [check 19:14] problem. The [unclear 19:15] problem is being spun out right now. It will be out within the next month. It just came together a little bit more quickly.

But I wouldn’t necessarily go on a rant in terms of how far along they are or how soon they’re going to be in the clinic. It’s all neck and neck. That’s how it should be. We have always been very careful to prioritize the ones that are at the most difficult, most challenging, most neglected so that they’ll catch up.

(00:19:43) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So I was thinking about the seven types of damage. Liz Parrish, she has done one type.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Well two really.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: All right, two types of [check 19:52] so that covers two areas of damage?

[Aubrey de Grey]: Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok. Basically you’re going to have people which are covering some of the damage, but not some of the other damage and it’s a bit difficult to understand what that may look like.

[Aubrey de Grey]: We have to give our finger on the past [check 20:07] very carefully because you’re right, but the utility of this taxonomy, the seven-point plan that we have must never be lost sight of. The utility comes down to the fact that for each strand, even though there may be many examples of a problem within the strand, for each strand there is a generic therapy. So if you have cell loss, it’s just stem cell therapy.

Now, different organs have different cell types and they need different stem cell therapies. So if you get one working, that’s not the end of the story, but it is kind of halfway to the end of the story because the stem cell therapy, even though they’re different, they have an awful lot in common. That means that once you’ve got a couple of them working then getting the next one working is going to take much less effort and much less time. There’s much fewer unknowns so we can push that forward.

It also means that it’s easier to make a case whether to scientists or to investors that this is something that they can make money out of in a timeframe that they’re comfortable with.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So in a sense once you’ve made progress in one of these areas, you’ve gone to clinical trials and you prove that even if it’s one-tenth of the actual end-output you need for that area, you’re validated, you’ve got credibility and that will make it a lot easier.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Let me also emphasize that you don’t necessarily even need to get as far even as clinical trials. So the strand of SENS that has been most in the news in the past couple of years is definitely senescent cells; removal of senescent cells. In that case, the company that’s really the flagship in this area, Unity Biotechnology, which is somewhat associated.

We could not describe them as a spin-out from us, but some of the founders have worked with us and have been funded by us. That company was able to attract its first [check 21:48] respectable enough like mid seven digit money on the basis of ridiculously preliminary data. Not just that it wasn’t clinical. It was only in mice, but also it was genetic models of mice that gave no particular reason to expect that one would actually be able to create drugs. It was even accelerated aging model which are always unreliable and they still were able to make a lot of money.

Since that time, their data has improved. They’re now worth nearly a billion dollars so this is a big deal. They’re not going to start clinical trials until later this year.

(00:22:18) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow! This kind of leads on to some of the names you have in terms of the investing companies were quite big. You’ve got Juvenescence and you’ve got Andreeseen Horowitz, some huge names in the BC world and also Y Combinator. Has that made a difference? Why did these companies or these funders come in?

[Aubrey de Grey]: It’s beginning to. So some of the, well really all of the really early investors when the industry just was starting to begin three or four years ago, were private individuals using essentially, well starting with their own money. Juvenescence is an example. Jim Mellon and his colleague Greg Bailey, both very successfully invested in other areas and decided to get really into this. Other just private individuals decided to start their own thing.

It wasn’t so much a movement at the investor side of things at that point. But then after a year or two of that, things started to change. So Andreessen Horowitz, obviously as you said an extremely established name in BC, doesn’t do much Biotechnology. They still don’t. They decided to get into this area just because they’re with this one company, BioAge. Which again is not technically a spin-out from us, but we work very closely with them, that was doing bioinformatics. So Andreessen Horowitz is very heavily involved in informatics in general.

So it was just something that they felt that they could understand really and do well. They felt a bit comfortable with it, it looked promising and of course, they were right. The company’s doing extremely well. Then Y Combinator has got into this whole field more recently, just really in the past year. They have again, not had much influence on Biotechnology until recently. They decided to do that and furthermore, they’ve done it in a proper way.

They’ve done in a way that recognizes that Biotechnology just takes longer to get going than IT. So the typical deals that they would have had for IT companies would be more like three months to get to demo stage and then we’re only going to give you a few hundred thousand to create.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: More effective products.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Yeah. Whereas when you get to Biotechnology, they recognize the difference in its order of events to mobilize the time and the money.

Yes, they are very much very clear that aging is a major preoccupation of theirs. They want to get into a startup landing in the biology of aging as quickly as possible. They’ve already got a few companies which again of course we’re talking to. They are [check 24:34]. They’re literally on the same street of us. They’re literally two blocks away.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well that’s useful.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Yes.

(00:24:41) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok so you just mentioned bioinformatics and BioAge. I don’t know if you’re allowed to talk about BioAge. I heard they’re more of a stealth mode.

[Aubrey de Grey]: They’re not really stealth, no. In fact, they share about what they know quite a bit, but what they have done as a result though actually of successful fundraising is they have been able to go broaden beyond the bioinformatics side. So Christian Foley who started BioAge is… she made a name at Stanford in bioinformatics. But the predictive ability that she was able to demonstrate with her original very small team of people was so good.

It mainly focused on metabolomics, but now spreading out to other onyxes. It was so good that the funding came in that was sufficient to be able to do their own lab work as well as to validate some of the drug candidates that they were identifying in silico. So now I’ve heard that a number of very good lab scientists are working at BioAge as well; again, friends of us.

It’s an extremely mission-oriented company. They’re very, very strong on making sure that they don’t get diverted by short-term investors into doing the wrong thing. That’s not true only of BioAge. It’s true across the board of the companies we work with.

Lessons have really been learnt here. A decade ago, you had a few cases of very well meaning, very smart gerontologists going out and forming companies and getting investment to actually take things forward. Even though it was earlier days in terms of science. A great example would be elixir, a pharmaceutical study by Cynthia Kenyon and Lenny Guarente. Complete waste of time, but it became a waste of time because they got the wrong investors. Because they got people on board who were much more interested in short-term [check 26:13] than they were in actual long-term success and the whole thing ended up being a total clusterfuck. That’s not happening these days.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Is it because you’re advising?

[Aubrey de Grey]: It’s a bunch of reasons. Firstly, it’s because the founders of these companies recognized that risk and they’re very careful of what money they take. But secondly it’s because the opportunity exists to take money from people who are not going to do that; people who really are high-risk high-rewards type investor types who are very comfortable with long-term strategies and yet who also have sufficiently deep pockets to be able to be the major investors for a long time.

(00:26:54) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. Great. So you mentioned bioinformatics and I was wondering how important is that to the overall strategy? Because we especially saw [check 27:01] some of the data and the stuff they’re doing and I’m hearing more about that data. It’s obviously something that we talk about here for validation. Does that also have to be an area of investment to push this forward by being able to validate the discovery you were talking about with BioAge?

[Aubrey de Grey]: It certainly does and it’s not just validation either. Well a lot of it is, but the sheer ability to make predictions so that you don’t have too many things to validate is the key really. Another great example in our space is Insilico Medicine who also received a load of money and mostly from Juvenescence in that case. Again, run by a longtime and very ardent mission-oriented guy, Alex Zhavoronkov; great friend.

They are usually state of the art machine learning techniques to achieve really fantastic results in terms of prediction of not only new drugs, but also new activities of old drugs that could be repurposed and their aftermarket is shorter in that case. Yeah and they’ve been able to get very good investment.

I believe that bioinformatics will never do everything You’re always going to have to do a lot of bench work and everybody knows it, but it definitely has its place.

(00:28:10) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: All right, great. So I’d like to pass a little bit on to you actually because we chatted last time just about what you do. Do you do any tracking for yourself? Are you interested in any of these life extension? One of the things I’ve heard about quite a bit here is senolytics because some people see this as something short-term they can do to enhance their health spans and they can get to these technologies. What’s your view to this for yourself? Are you doing anything or are you interested? Do you think it’s not really worth it because you’re just waiting for the big stuff?

[Aubrey de Grey]: Everybody’s different in this. I always tell people, “Don’t do as I do; do as I say.” The reason I say that is twofold. First of all, I’m just well-built. I’m a really lucky guy. Well first of all, I’m lucky in that because of my providence in the field, I’m able to get for free the kind of really top of the range analysis of my metabolic state that would normally cost ten thousand dollars and I’ve done that maybe five times over the past fifteen years.

(00:29:04) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: What kind of analysis?

[Aubrey de Grey]: They measure 150 different things in your blood and all manner of physiological and cognitive tests; you name it, they do it. I always come out insanely younger than I actually am like fifteen years younger. What that means in terms of what I should do is I have to be very conservative. Respecting how little we really understand about metabolism. It’s a case of if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.

So the fact that I actually eat and drink what I like and I don’t even do much exercise, nothing happens. I’m doing fine and so I might as well, but that doesn’t mean that I’m going to do fine forever. I always have to pay close attention to any early signs of something going downhill.

The other way in which I recommend people not do what I do is because of my position and my advocacy role, I’m constantly on the road. I definitely don’t get nearly enough sleep and that’s definitely bad for me. But I figured it’s probably [check 29:57]. I’m hastening the defeat of aging, but I’m [check 30:00] in my life.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely. Yes it’s really interesting because I’ve spoken to a variety of people here and they have got very different strategies. One person I spoke to, he’s basically stacking everything that you’ve seen here. Some of his markers, he actually isn’t in such great shape so the higher risk is worth it to him. But if you’re starting from a great place then as you said, until they’re proven, it’s not worth taking these things.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Precisely. Senolytics, for an example, the [check 30:27] is definitely one of the things in my seven point list and so I’ll definitely be willing to do that at some point. But at the moment, it makes sense for me to wait and see and let these therapies become more effective and more, you know, more tested. That’s happening so fast now that in one or two years down the road would make more sense to me.

(00:30:50) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. It’s a very strategic unit. It really fits with what you’ve done with SENS Research Foundation. So this is the last thing. Where can people, I mean two things. Have you got an ask for the audience? Anything that you’d like to tell them?

[Aubrey de Grey]: Sure, totally! At the moment, as I said we’ve got this burgeoning of the rejuvenation technology industry with more and more investors realizing that this is the next big thing and it’s starting to come in too. But there is still this residue of projects that absolutely vitally need to be taking fold as well and yet are not yet quite at the point of investability even from the visionary end of the spectrum of investors. That’s why the foundation still exists.

Now the unfortunate part is that your average investor is not totally keen on giving money away. They got wealthy by not giving money away indiscriminately. Therefore if anything, the burgeoning of the industry side actually makes that much harder for us to bring money in philanthropically.

As such, we are still way short of what we need in order to go as fast as the difficulty of the science allows. I think we could still at least double the rate at which we make progress on the hardest and therefore the most essential aspects of this work. Absolutely I haven’t asked. I say anything you can do to help. We have a nice friendly donate button on our website, sens.org and if you want to give us more than that then you know where and how to contact us.

Other than that, if you’re not wealthy, you can still give us ten dollars, a hundred dollars a month; these add up. But also advocacy; very, very important. People who are not billionaires and not scientists may feel that they can’t do anything, but that’s not true at all because the quality of debates, the quality of understanding and discussion of this area is still being unbelievably strongly held back by the desperate need for most people not to get their hopes up about this.

This is what drives what I’ve called [check 32:47]. They hear rationalizations that allow people to trick themselves into thinking that aging is some kind of blessing in disguise. I get so frustrated that people just refuse to open their eyes because it’s holding us back. That lack of enthusiasm is making people not support this work financially. When I say people here, I don’t mean just individuals, I also mean companies and governments.

So shunting the course of debates just as you’re doing right now by having me on camera, this is what needs to be done.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Perhaps more of these conferences. More people attending the conference, getting more involved, more engaged.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Totally. RAADfest is growing. Yeah it’s a fantastic event. We also have our own event in Berlin every year, every March. The emphasis is a bit different. It’s more exclusively science at that conference, but the crowd is the same. The kind of connections you have, it’s across the whole spectrum from the hardcore scientists who are getting the work done at the lab through to all the advocates, the investors.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Aubrey, thank you so much for your time.

[Aubrey de Grey]: My pleasure.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s great to have you again. Yeah.

[Aubrey de Grey]: Thank you.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Can you go first? We were just talking about how we we’re going to talk and it just failed.

[Britton Schneider]: I’m Britton Schneider. I work with Liz at BioViva.

[Liz Parrish]: My name’s Liz Parrish and I’m the CEO of BioViva.

(00:34:15) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: You know me or you should do by now so I’m not going to introduce myself. This is going to be a great little chat based on some of the stuff I learnt yesterday from your presentation. Just talk about what BioViva is doing and also what you personally have done yourself which is one of the highlights. So first of all, just for the audience because many of them probably don’t know who you are and what you do. What do you do? Who are you?

[Liz Parrish]: I’m the CEO of BioViva. I’m considered the woman who wants to genetically engineer you. I want to create humans that are healthy and don’t die of the diseases of aging and therefore bring treatments back to children who are dying of critical diseases now that will cure them of their diseases.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s a really good introduction.

[Liz Parrish]: I’ve been doing it for a few years.

(35:00) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So Aubrey de Grey just called you patient zero so you apparently have several names. Are there any others?

[Liz Parrish]: Well depending on who you talk to.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Good ones! Well if you get any bad ones. Any bad ones?

[Liz Parrish]: I don’t know of any bad ones actually. I don’t think that I get too much right now.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s good. Does Brit call you something? Does she have a pet name for you?

[Liz Parrish]: She calls me “you’re late.”

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok.

[Liz Parrish]: That’s how I know myself.

(00:35:21) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s the main thing there. Ok so what does BioViva do and what is its mission?

[Liz Parrish]: BioViva is a bioinformatics platform now. We’ve changed our gears. For two years, we tried to be a program that actually treated patients directly with gene therapy. We’re looking at regenerative medicine gene therapies; gene therapies that reverse the biological clock, gene therapies that create upregulation of regeneration in the body, gene therapies that increase muscle mass for the aging population and therefore creating cheaper cures for kids with muscular dystrophy.

So every one of the therapies that we talk about today, there’s an aspect that can be used in childhood disease. But we wanted to do that. We wanted to treat patients correctly, but we found out we couldn’t do that. There was not a regulatory framework for us to be a U.S. company and do that, but the most important part of treating patients is the data; what happened when a patient was treated.

So we actually became in partnership with an exclusive partnership with a company that’s offshore of the U.S. It can broker deals between patients and doctors to do gene therapy and we get access to all the pre and post data. We find out exactly what’s been done to the patient and then we look at the biomarker panel that we’re developing with our bioinformatics program and we see where gene therapies work and where they don’t work.

In research and development, we are actually starting to design our first viral vector that will get multiple genes in at one time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you are doing R and D still?

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah, we are.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Then you license that out, but you just don’t clinically deliver it?

[Liz Parrish]: No. The thing is you never want to fall in love with your hypothesis. So we don’t want to be a telomerase inducing gene therapy. We don’t want to be just a [check 37:06] inducing gene therapy, PCG-1 alpha, FGF21, Folistat. If you fall in love with your hypothesis, you’re going to try to prove that it works.

We’re a testing platform to see what works. We’re going to bring other companies through that have therapeutics that we will actually give them their first human data. So why would we do this? Why would we do medical tourism? It’s a multi-pronged approach.

Number one, you give patients access to therapies they couldn’t get otherwise. Often, these patients are in dire need of something and the regulatory system and their doctors would just let them die rather than treat them, rather than take the risk because we’re very risk-averse. So number one, you’re helping patients.

Number two, you’re helping biotechnology companies get the first data on whether their drugs work in patients and where they work and where they don’t work.

Number three, de-risking investment in biotechnology. Right now, biotechnology has a 94% failure rate through phase studies. Investors don’t want to invest, but if you plop down the data on ten, twenty, a hundred patients and what happened, we’ll know what drugs will work before we start to run them.

Do we think that drugs should go through a regulatory service? Absolutely. They should go through a regulatory service so they can be sold widely to a wider audience and help more people, but people need access now. The human model is the best model organism to work in to find out if drugs work for humans.

(00:38:30) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you completely pivoted the company. So before you were actually developing them and now you’re, just to get it straight, you’re not doing any R and D and development at all? Or you’re doing a bit, but mostly you’re going to be sourcing the R and D from other companies?

[Liz Parrish]: Instead of actually trying to run one gene to find out how well it works, we use the meta-analysis so it’s called bench to bedside. Where we are doing the development and research and development is the driver, the vehicle; what gets the genes into the cell. So we’ll let other gene companies and research institutions run all that expensive pre-data, but then we want to see what happens in patients when we look like we do have a promising drug.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you’re going to select the most promising ones?

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah, that’s right. So the reason we would look at telomerase induction is it actually has decades of research done on it. Nobel prizes have been given out and fantastic, very inclusive research papers have come out. Maria Blasco just put out an exhaustive scientific paper about how telomerase induction does not cause cancer, it may actually protect against cancer. These are the things that we need to see, but if we don’t apply them to humans, they have zero value.

(00:39:42) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So basically what you’re doing is you’re saying the regulatory environment is not going to let us do any of this and it’s very expensive to do the clinical trials. So we’re going to let less risk-averse people or maybe they’re in a situation where they’re at high-risk of dying or they have a very damaging condition already and so it’s in their interest to reduce risk. So they can do it for medical tourism then you can get the data and then fast forward and validation.

[Liz Parrish]: Fast forward those drugs. Actually, I think that our platform in the next two years, we’d like to prove ourselves and then we’d like to have the regulatory service look at our platform. If we actually ran drugs like we’re designing to run drugs, this is actually what we want. Don’t hide any of the data, show the data; where does it work, where does it not work.

That way we have a clear picture of what’s going to happen. We already take drugs that aren’t necessarily safe, but we’re none the wiser. We get a pamphlet, you get a bottle of statins, you get a pamphlet, but if you look at the Cochrane Report, a statin will save one in 164 patients from getting a stroke, but one in ten will get Type 2 Diabetes and one in 50 will get dementia from taking the drug.

We don’t understand our risks to begin with, but we’re looking at gene and cell therapies, we’re looking at just upregulating a beneficial protein that has decades worth of data on it in the human body to push regeneration. Not only may these patients actually recover from their disease if we’re lucky, they will be spearheading the technology for the future.

Our risk aversion just has developed so many myths around living as if we’re not actually going to die, but how is anyone actually going to solve the problem. Taking a gene therapy is the type of people who want to buy an experience, but they are also health investors; they’re investing in their future.

(00:41:30) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: You probably are talking to a lot of people who are interested in taking gene therapies, what type of people is this? Just to get some on the ground information. i’m sure these kind of people contact you. What kind of population are interested in this?

[Liz Parrish]: We get thousands of people who contact us and are interested in taking a gene therapy and they really span the gamma and some of them were excruciatingly heartbreaking earlier on because we didn’t have ways to treat patients. We had people come through with sick kids who have probably died since then because there was no option. People with muscle disorders, heart disorders and various really sick people. But also we get some pioneers. Some people that hands down would take any therapy to be part of the experience of spearheading technology for the human race.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Like some healthy people?

[Liz Parrish]: Some healthy people.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Like you?

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah, some not so healthy. Well if you look at biological aging, by the time I was 40, I’m not very healthy. These therapies will be used in sick people. We’ll see if we can regenerate a kidney, we’ll see if we can regenerate a liver, we’ll see if we can create some more beneficial cognitive effect in patients with Alzheimer’s. But then we’ll work them back to people in less disease state and soon, we’ll be using them as immunizations. How soon that happens is how fast we start working towards that data.

(00:42:52) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So what is the timeline for this model you’ve put in place? Is it just started? Is it 2019 you’re going to have some clinics in specific countries in the world that’s run by this organization called IHC?

[Liz Parrish]: IHS?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: IHS.

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah, Integrated Health Systems. Yeah so we’re starting now and already patients are signing up to talk to doctors. They are very interested in therapeutics so we’re hoping to start generating our data in 2019, but how clean that data is and what that data means is going to take us a little bit of time to generate. So we’re looking at a huge biomarker set. We’re looking at a multi-comeback…

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: There are four monstrous slides. I think I’m a data geek. It was ridiculous.

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah. So we’re going to pull from publicly available data sets, but we’re going to be analyzing, the first company in the world that analyzes what happens when you do regenerative gene therapies in humans.

(00:43:44) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you’re going to ask the clinics to collect this data? Because it was a very extensive amount. So do you need equipment like special MRIs?

[Liz Parrish]: Well we actually work with the doctor. So the doctors who are exclusive to IHS are actually exclusive to giving all of the data to BioViva.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That’s the new agreement?

[Liz Parrish]: Right, and there is protocol. So to every gene therapy, there’s a protocol, there’s a list of markers that have to be taken before a patient can be treated.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok.

[Liz Parrish]: It is pretty broad.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It wasn’t all of those though, was it?

[Liz Parrish]: Remember a lot of it is done in blood work. So a lot of those biomarkers come from blood work, DNA testing, methylation testing. Other markers come from imaging. So imaging is really important when you’re talking about brain health, when you’re talking about muscle health. When we’re talking about whole body health, we want to visualize what’s happening.

(00:44:38) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Are you going to basically standardize the definition of the type of data and also how to record it?

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah, absolutely.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: But who’s going to actually collect the data? Are you going to collect the blood samples and send it to a U.S. lab or a centralized lab? Or are there going to be labs all over the place or just the local ones?

[Liz Parrish]: So that depends on what labs the doctors work with, but they’re all the big companies. We work with generally the standardized labs.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Like [check 45:01]?

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah. Exactly. But we also work with some smaller companies that have some protein discovery methods, proteostasis, demethylations.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: This specific test is more advanced.

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah so we’re not only looking at the old biomarkers that we used to look at c-reactive proteins and a blood glucose level, but we’re looking at these markers that will be really important in five years that really will be more specific than the other biomarkers in the coming years. That’s how we’ll find the real true biomarkers of aging that can give us a close date to the biological age of what your due date might be on your body and how we could actually change that.

But by doing regenerative therapies, we might be able to reverse engineer some biomarkers of aging as well.

(00:45:50) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: What does that mean?

[Liz Parrish]: It will give us a new view, a new insight of reversing pathology in the body and regenerating certain [check 45:58]. So for instance, even when you’re young, you’re actually generating damage. Your cells are degenerating in a slow form way. This isn’t just something that happens as you get older. Your body is developing so we have the illusion that we’re not accumulating damage, but in fact we’re accumulating damage over our entire lifespan.

We’ll be looking at bodies hopefully with regenerative medicine in these gene therapies that actually start to restore damage. That’s a reverse process of damage. Therefore we’ll get the insights of what that actually means with biological age. First, we’ll start pinpointing it back to a healthy body. A healthy what I call 1.0 body with a 2.0 body may have different biomarkers that give us insight to how to adjust to what is happening with aging in the body right now in the 1.0 body.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I’m not 100% following with this.

[Liz Parrish]: Sorry.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Sorry guys.

[Liz Parrish]: It’s probably me.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So 1.0 is someone.

[Liz Parrish]: 1.0 is a human who has not been given the gene therapy.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok. All right. So you’re saying once you get a gene therapy, you may not be normal? You might be something different, but it’s also healthy?

[Britton Schneider]: Ideally, yes.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Or it might be healthier?

[Liz Parrish]: You’ll be regenerating, well that’s what we’re hoping, is to put the body into a homeostasis; stronger, smarter, faster, healthier.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So that’s the 2.0?

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah. That’s any person who has gone through a regenerative gene therapy who has an upregulation of a protein that is designed to actually reverse damage in the body.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok so I’m following you now I think.

[Liz Parrish]: I nerded out.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: The same way we’re upregulated with many detoxifications.

[Liz Parrish]: I went too far.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: You talk fast. Not as fast as Aubrey, but he’s hard to keep up with. So for instance, we have many detoxification processes and enzymes in our body, you could upregulate some of those and then you could drink alcohol all day and not worry about it for instance, like Aubrey does.

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah, that’s true. That’s one use of our time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well I’m not saying it’s the best, but basically that’s what you are saying. We would have these abilities.

[Liz Parrish]: Yes of course. I’m all for people enjoying their life and living the life that they want to live.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: We’ll go to the gym less and be stronger.

[Liz Parrish]: Yeah exactly. Well that was one of the things with my therapy. I worked out five days a week, I ran about 25 miles a week and after my therapy, I got on plane after plane, I had jet lag, I wasn’t working out. When we did my second MRIs, I was really worried because I had not been exercising, but the muscle mass was bigger, the white fat was down and my insulin sensitivity was up.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok Liz.

[Liz Parrish]: So that’s fantastic!

(00:48:41) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: I did want to talk about this of course I did. So on this podcast, on this show, we’re into self-experimentation so you’re a good fit and tracking data on it so that’s one of the key things. But I wanted to make sure we covered all the business and what you’re up to there because we’re also excited about the data. Because my belief and probably most of the people following the show which includes BCs, entrepreneurs, software experimenters and biohackers, is that data is one of the keys to everything because it will stop us running around in circles.

[Liz Parrish]: Yes, exactly and boy did we learn a lot about data. When we started this company, I found an investor. He said I’ll invest in you taking this therapy to embark on this and show that we can reverse biological aging. We have really big plans, but we didn’t really have a list of things that we really needed to do. So all I did was a lot of blood work, I did MRI imaging then I did telomere length. But today what we know is there’s so much more that we could do.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you wish you knew probably more?

[Liz Parrish]: Of course, but that’s how you get there.

(00:49:38) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: What exact baselines did you take?

[Liz Parrish]: That’s when you saw my biomarker list, it’s extensive; it’s exhaustive.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well because we don’t know which ones it’s going to affect.

[Liz Parrish]: No, we really don’t and we actually still don’t know what biomarkers [check 49:48] that we look at now. We’ve hunted LDL cholesterol like a witch hunt and yet people with high LDLs sometimes never have heart attacks.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I have high LDL, but I’m not worried about it because my particle count is low.

[Liz Parrish]: There is the group in Italy that have a gene. They never develop atherosclerotic plaques, but amazingly they have really high LDLs and then people with high HDLs and low LDLs die of heart attacks.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So it’s a perfect example.

[Liz Parrish]: So we have a long ways to go.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Because this biomarker is used everywhere and we don’t even know what it is.

[Liz Parrish]: Everywhere. Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s called bad cholesterol, but we really don’t know what it is.

[Liz Parrish]: So we need more data. We need to look at phenotype, we need to look at anatomical, physiological data. We have a long, long ways to go. So even before BioViva came along and started throwing regenerative gene therapies into people, we had a problem with biomarkers and we’re just pointing out that problem.

(00:50:40) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ok. So you’re going to collect a lot of data, but how are you going to get the value right because there are a lot of biomarkers. Are you going to put AI on it or what are your plans for this leverage?