Sometimes on this show, we discuss using supplements as tools to get desired results. Examples in past episodes included curcumin, activated charcoal, NT factor, Greens powder, oxaloacetate and many others.

I’ve been aware for a long time that not all supplement products are equal in quality. For instance, if they actually contain as much of the active ingredients as the label says on them, or if they are contaminated with heavy metals or pesticides, for example.

Last year this issue was given more publicity when the New York State Attorney General’s office investigated supplements found at GNC, Target, Walmart and Walgreens, and sent ‘Cease and Desist’ letters to each for some of their supplements that neither contained the active ingredients, and at times contained other undesirable ingredients that weren’t listed on the labels.

The unfortunate takeaway is if you truly want the results from supplements — so if we talk about results that can be achieved through a supplement on this show – then you can’t just take it for granted and buy any supplement. You have to make sure they contain what you want and don’t contain what you don’t want.

In practice, how do we do that? I’ve been using a lab service for a few years now that tests and reports on the quality of supplement products. So I can select the products that will achieve the results while minimizing the cost. Sometimes you don’t need to buy the most expensive brand to get the best quality, which is kind of cool.

The service was ConsumerLab.com, which is a subscription service, so unfortunately, you have to pay. However, the good news is that an open alternative is now available that has been publishing extensive lab testing data on popular supplement categories.

That company is Labdoor.com. If you have the internet available it will probably be useful to check out the rankings the company is publishing while listening to this episode to see what the end result is, and what they’re actually publishing.

“I think there are categories where 70 percent of products fail, there are categories like creatine where 10 percent or fewer products fail. And then there’s kind of the in-between zones where, with fish oil, about a quarter of the products have rancidity [fat oxidation] issues. And so we’re filtering that, and that’s a part of our [supplements testing] purity score.”

– Neil Thanedar

Today’s guest is Neil Thanedar, CEO and Founder of Labdoor.com, and Founder of Avomeen Analytical Services, which is a company that specializes in product lab analytics to see what they are composed of. Labdoor is now four years in the making and sets to start growing at a faster pace and covering more supplement categories now that they’ve got some sort of funding behind them.

In this interview, Neil walks us through the types of analysis they run on supplements to understand their quality and some of the most interesting and useful results they found in the supplement markets. It features highlights, such as we shouldn’t really be trusting user reviews that you find on the internet on places such as Amazon – because there doesn’t seem to be much of a correlation. And there are other big similar takeaways, which, I’m sure, goes against what we’ve all been doing.

What You’ll Learn

- Neil’s research interests and orientation towards quality control supplement testing (3:57).

- Labdoor is a spin-off business, diversifying lab testing services compared to what’s offered by Avomeen (5:40).

- Labdoor and Avomeen are split in leadership between Neil and his father (7:50).

- A consumer-aligned model and efforts to eliminate bias in producing objective information (8:03).

- The major quality control issues with dietary supplements (10:04).

- Defining supplement quality and criteria used for rating supplements (11:13).

- The technologies used for testing supplements and the science behind interpreting results (12:19).

- Customizing supplement ranking formulas and tailoring results to individual customers, ex. vegan or child categories (18:54).

- Establishing accuracy in nutrient analysis and maximizing trust in results (20:25).

- How Labdoor manages an active role as part of the supplement industry (22:54).

- Dealing with testing newer or complex composition supplement products, where research is still accumulating (25:05).

- Consumer demands and targeting of testing results to differing audiences (27:15).

- Labdoor’s role in supporting an informed market (29:21).

- Overview of tested categories of supplements (33:10).

- Discovering products and prioritizing particular supplements testing (39:15).

- A severe lack of price correlation in the supplement industry (40:58).

- Cooperating with companies when Labdoor testing does not confirm producer certificate of analysis testing results (42:08).

- Labdoor’s plans for reaching out to manufacturers more proactively (47:23).

- The potential of re-testing for capturing trends in the supplement industry and increasing confidence in obtained data (48:30).

- Case studies and key takeaways for particular categories of supplements (52:19).

- Little brand correlation in same category products and guidelines for choosing supplements (54:21).

- Caveats for non-scientific approaches towards choosing supplements (57:20).

- Future prospects of wide-spread product testing aimed at empowering consumers to make science-based health decisions (1:01:44).

- Reasons for re-organizing the supplement market, such that the best products are making the highest sales (1:03:59).

- Scientific or practical business assumptions which Neil has changed his mind about (1:06:06).

- The biomarkers Neil tracks on a routine basis to monitor and improve his health, longevity, and performance (1:08:21).

- Recommended self-experiments for improving mental performance (1:14:07).

- The best ways to discover the field of supplement testing (1:15:55).

- How you can best connect with Neil or find out more about Labdoor (1:18:54).

- Neil’s request for you – The Quantified Body audience (1:20:32).

Neil Thanedar, LabDoor

- Avomeen: A chemical analysis lab specialized in failure analysis work (when products go wrong). Initially, it was started by Neil but is now run by his father – a scientist continuing his work and research in his retirement years.

- Labdoor: A company currently run by Neil focused on providing scientifically-backed analysis and ranking of dietary supplement products. The company offers objective information on supplements and aims to empower people to make informed decisions. Check out Labdoor’s supplement rankings.

- Labdoor’s Facebook & Reddit: The two fastest ways for you to reach out to Labdoor. Hundreds of questions have already been answered on these forums and Neil hopes new ones will spark lively debates on topics across the field.

- Neil’s Twitter: Where Neil shares his ideas about testing and his opinions on how Labdoor touches other industries.

Recommended Self-Experiment

- Tracking Time: Keep track of how you spend time for 10 days in a row with an app such as Hours. You should discover many useful takeaways such as areas where you waste the most time or activities you should cut. Neil suggests repeating approximately every 6 months to track improvements and optimize over time.

Tools & Tactics

Supplementation

- B Complex: It contains Vitamin B12 – a molecule which is used in the metabolism of every cell and acts in DNA synthesis and regulation. B complex also contains folate which is needed for DNA repair and proper DNA methylation – see episode 5 with Ben Lynch. This product contains the active forms of B vitamins increasing their bioavailability.

- Curcumin BCM95: The active ingredient of turmeric, also found in limited amounts in Ginger. Curcumin is a potent anti-inflammatory and cancer preventative molecule. Previously we have discussed this supplement in the context of lowering oxidative stress or inflammation in episode 4 with Cheryl Burdette and episode 25 with Josh Fessel.

- Activated Charcoal: This is a medical-grade purified product which is highly absorbent of toxins. It promotes a healthy digestive track and improves brain functionality. Taking activated charcoal reduces the body’s toxic burden – a subject discussed in episode 23 with Kara Fitzgerald. This is a lower cost (value for money) Activated Charcoal option.

- NT Factor EnergyLipids: A blend derived from soy lecithin extract specifically. This product is formulated and used for supporting memory and cognitive function. There’s also an NT Factor Energy Wafers option which is a chewable product packaged in pieces.

- Greens Powder: A mix of alkalizing green foods, antioxidant rich fruits, and support herbs. This product is used as a dose of whole food nutrition – essentially aiming to supply a healthy background of nutrients.

- Oxaloacetate (Aging Formula): A metabolite of the Krebs Cycle which improves blood sugar regulation, improves energy levels, and increase endurance. Previously we discussed oxaloacetate as an anti-aging supplement in episode 30 with Alan Cash and in the context of blood glucose regulation in episode 22 with Bob Troia.

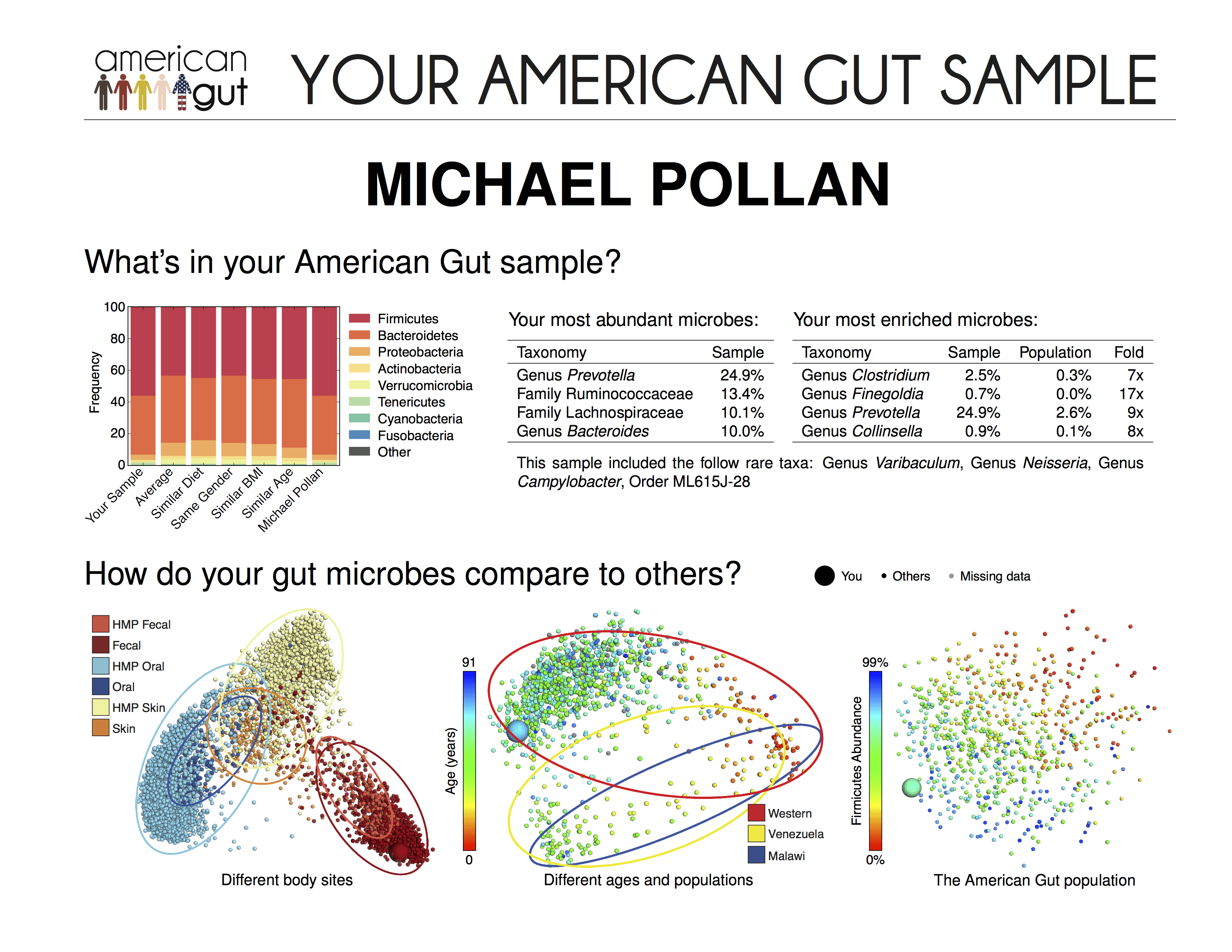

- Fish Oil: This supplement is useful against inflammation. Fish oil can be used post workout sessions or if inflammation is part of a disease state. Labdoor tests EPA and DHA content (beneficial Omega 3 fatty acids) in fish oil supplements. According to their data, often there are products which contain 50% Omega 3 instead of the labeled 90%.

- Lypo-Spheric Vitamin C: These are liposome encapsulated vitamin C tablets and this maximizes the bioavailability of the active component. Previously we have discussed Vitamin C and its potential for preventing colds in a timely manner by tracking Heart Rate Variability (HRV) in episode 41 with Marco Altini.

- Calcium: This supplement is aimed at improving the composition of bones. Calcium also plays a key role in muscle contraction thus this mineral supports neuromuscular health. The major benefit of calcium is lowering the risk of developing osteoporosis.

- Magnesium : This mineral in supplement form is used to support nerve, heart and muscle functionality. See episode 17 with Dr. Carolyn Dean for testing and fixing magnesium deficiency.

- Zinc: An essential mineral which plays a role in many enzymatic functions. Zinc supports immune system function and is an important component of the body’s antioxidant systems.

- Creatine Monohydrate: This product is targeted for using after workouts to aid in the recovery process. Approximately 5-10% of these products are faulty, according to Labdoor supplement testing results data.

- Garcinia Cambogia: A small fruit traditionally used to enhance the culinary experience of a meal and as an aid to weight loss. Garcinia cambogia was the worst category recorded by Labdoor. Up to 70% of products in this category do not actually contain the active ingredient (defined as less than 10% of the labeled ingredient quantity).

- Ginseng: This supplement is effective for mood, immunity, and cognition. Examining the ginsenoside content is important in these products because Ginseng quantity is different from the active ingredient. This causes consistency problems because extraction processes differ. Neil advises patience before purchasing these supplements and, of course, waiting for Labdoor’s data on particular products.

Diet & Nutrition

- Protein Bars: In the future, Labdoor plans to take on testing food beverages. For example, increasingly protein bars are marketed as a meal replacement, thus approaching the supplement (or functional food) category. Eventually, even well-known products such as a McDonald’s Big Mac, a Chipotle burrito, or liquid beverages such as Pepsi could be tested.

- Baby Formula: Manufactured food products targeted for feeding infants under 12 months of age. Often, these are manufactured using methods similar to those used for the production of supplements.

Tracking

Labs Tests

- Liquid Chromatography: Chromatography is a diverse set of laboratory techniques for the separation of mixtures. Detecting the concentration of specific substances out of a whole is key for objective supplement testing results. In liquid chromatography, the mixture is turned into a liquid phase which moves through a column or plane (solid phases used for detection). Individual chemicals can be detected based on a constant property, ex. by affinity for the solid phase coating material.

- Gas Chromatography: This method is used for analyzing compounds that can be vaporized without decomposition. In vaporized form, chemicals travel through a column at different speeds and reach the detection surface at different times – known as retention time. This is a constant for individual types of chemicals and is the principle behind detecting particular types of chemicals in gas chromatography.

- Mass Spectrometry: Mass Spec or MS as it is known is becoming increasingly popular for analysis of all types of samples from testosterone and other body metabolites or proteins to understanding the composition of any material.In a typical MS procedure, the sample is initially ionized by bombarding it with electrons. These ions are then accelerated by subjecting them to an electric or magnetic field. Individual substances are detected according to their mass-to-charge ratio. Ions of the same mass-to-charge ratio undergo the same amount of deflection on the detection surface. This is transferred into information about concentration.

Liquid / Gas Chromatography is often used as a pre-analytical method for preparing isolated sets of chemical subgroups, before digging deeper using mass spectrometry to obtain accurate supplement testing results.

Apps

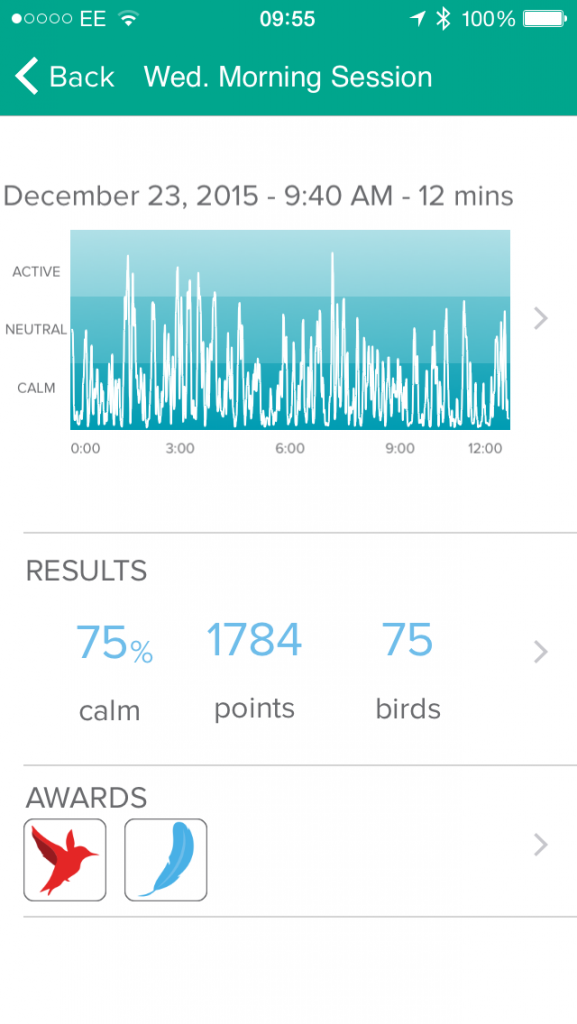

- Headspace: A meditation, or mindful awareness, training app. It is useful for improving mental performance, to relieve anxiety, and increase endurance.

- Lucid: An app focused on mental training for professional athletes.

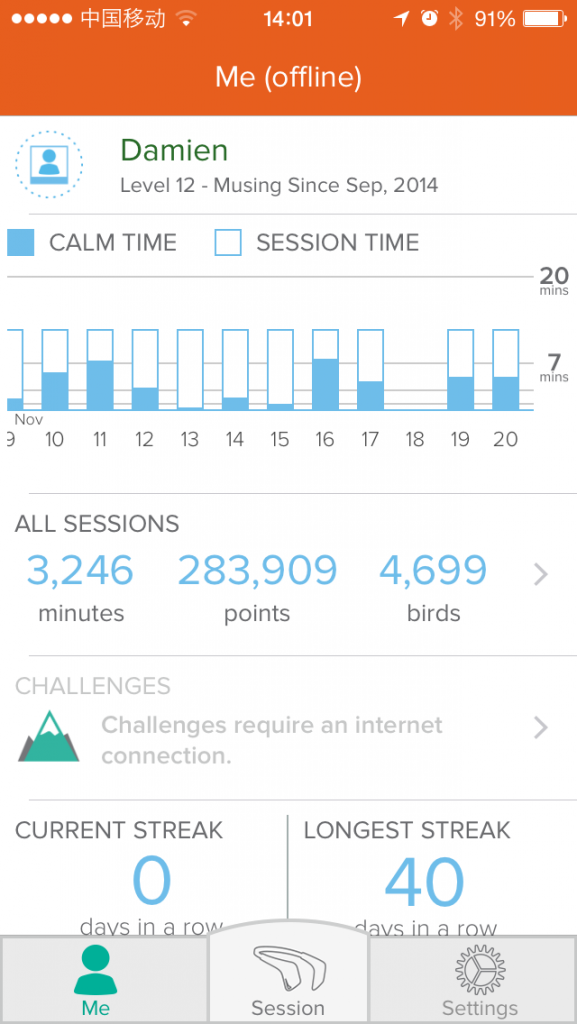

- Hours: An app used for tracking activities throughout the day, thus mapping time expenditure. This is useful for improving mental performance. Because tracking itself can be time-consuming, Damien suggests undertaking focused projects – one lasting a few weeks before moving to the next.

Other People, Books & Resources

Organizations

- ConsumerLab: A company offering supplement testing service. Damien used ConsumerLab Reports until Labdoor appeared on the market and started offering supplement testing free of charge.

- Thorne Research: A company manufacturing dietary supplements, separated in programs tailored towards health categories, ex. cardiovascular or immune support. Their products are usually sold through doctors, thus Labdoor has missed these in their initial supplement testing categories.

- Life Extension: A manufacturing company producing supplements including vitamins, minerals, herbs, or hormones.

- Elysium: A relatively new company gaining ground in the supplement industry, partly due to their science-strict operational and marketing model. Elysium is sponsored via venture capitalism investments – a business model different from Labdoor’s.

People

- Gary Vaynerchuk: Recognized by Neil as an important voice in the understanding the link between marketing and consumer trust.

Other

- Yelp: Neil draws a parallel between Labdoor and Yelp – a service specialized for ranking business of different categories ex. restaurants or shopping venues. This comparison demonstrates that Labdoor requires customer and manufacturer feedback to grow its business and to accomplish more ambitious challenges.

Full Interview Transcript

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, absolutely. Thanks for having me.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: You’re in a pretty niche area. There have been a couple of companies around which have been testing supplement products for a while. And of course there’s been a fair amount of news over the last year or so talking about the high variability in supplement quality, and whether we’re getting what we want.

So I was just interested in how you got into this whole area. Where did this start for you?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, absolutely. I grew up in research, I grew up in science. My dad’s a Ph.D. Chemist. When I was two years old he quit his job as a researcher and started his own lab. And it was just him for a couple of months, and he slowly grew that lab all the way up until I was in college. So he had retired by the time I was in college.

When I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my career, the first thing I really wanted to do is, I had really thought about biotechnology or inventing new medicines. And those had been the first things I had thought of. And throughout the process, I found out that the existing process, the existing medicines and supplements just weren’t clean; they weren’t safe. And so I jumped right back into the same industry that my dad did, which is quality control.

And so right out of college I started a lab. It was a chemical analysis lab called Avomeen. We did product development and failure analysis work. We figured out for manufactures when something went very wrong: a pill had a black dot on it, your baseboards were yellowing, there was an odd smell coming from a multivitamin. Any sort of something going wrong, the company would come to us, we would do all of the testing required to figure out what they should go and fix.

(00:05:40) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: You just mentioned baseboards. What are baseboards?

[Neil Thanedar]: Literally the baseboards like in the floor, that connect the floor to the carpet. That little white strip? That’s actually a product that we did once. The white boards were turning yellow as soon as they were installed.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you actually started from analyzing a broader spectrum of products, not just dietary products.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah. It was anything from that to household cleaners to a sunscreen to a multivitamin to even pharmaceuticals. Generic versus brand name medication.

And so we were doing it, but we were doing it in a very reactive way and we were doing it for manufacturers. And really one day I just had the idea that really we should do the opposite business.

What if we could, instead of being reactive we could be very proactive. We could go into a Walgreens or CVS and buy every product off the shelf and pretest it. So you would already know if it was good or bad. And if something failed, you would know ahead of time.

At this point, I had — as kind of a back-story — my dad had come in and started working with me to come out of retirement. He was starting to work at Avomeen. And so what I decided was I really felt like LabDoor needed its own focus. And so we kind of split up, and he went and he’s taking care of Avomeen now, and I fully run LabDoor.

So this was, for me it was a new way to work in the business. I kind of just jumped into the industry expecting it to be like it always was, and then just one day being the new person. I was just like, hey this is weird, why don’t we just start by testing everything?

(00:07:15) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Cool. So how long has Avomeen been around?

[Neil Thanedar]: So that company has been around for about seven years now. And LabDoor has been around for just over four. It’s been all LabDoor for me for the last four years.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. Cool. It’s very interesting. So it’s always good to see a family business. Your father’s kind of proud of you for carrying it on, the whole research lab area.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, it’s so interesting. We always talked about it, but it was never something he asked me to do. It was just always interesting to me. And I think the science is so fascinating, when you figure out exactly what’s inside something. You get to break things down and you get to reverse engineer, it’s just fun.

The problem in the industry is really just, how do you get paid. Consumers need to see the data but they’re not going to pay ahead of time. It’s really just paying for this testing that’s the hard part.

(00:08:03) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, yeah. So I guess you’ve got a slight advantage because Avomeen is associated with you, but how does LabDoor get paid so that you can do this for everyone else? Because the information is available for free, right?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yes. And so, what we want to do is do all the testing ahead of time and help you have all the data to make the research decision. And then what we’re finding out is that people, the next thing you’re doing is buying. And so if we just affiliate links down, we’ve got 10 percent of the conversion. And that really is most of the business.

And I think it’s what we, we love that kind of alignment with the consumer. So you’ve got the sense of I don’t get paid unless you actually find something you like. If you return it, we lose the commission. It’s this whole process where we can really be performance based.

And it’s also something where it’s sustainable. Every single day, there’s going to be tens of thousands of people who shop this site. They’re going to buy stuff, and that’s going to support the next round of testing.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. And I’m guessing it doesn’t matter what they buy. Are you putting Amazon links on most of the stuff?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah. So it’s really easy to put it on every single product. And we get some debate about this. The D and F products have affiliate links on them too.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: The DN…

[Neil Thanedar]: The D and F. So it’s A through F. Every single product has the link.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Well, I think that’s the way to go because you’re unbiased.

You’re not there to promote one product versus another. It’s just that you provide your objective information, and if someone buys something from using the information on your site to make that decision, you get a commission. But like you say, you’ve put a few links on the worst products and the best products, so there’s no official bias there.

I bring that up because there are some sites out there on the web which have been out there for quite a long time, and I’m sure people are aware or these – which are basically just affiliate review sites. And they have their number one product where they are getting paid, and all the others they are not getting paid. And obviously, they are just trying to cash in there.

But yours is a professional company without the bias.

(00:10:04) [Damien Blenkinsopp] Okay, so let’s talk about supplement quality to actually understand what the issues are. What is the context for us first? Why should people be interested or worried about dietary supplement quality?

[Neil Thanedar]: I think there are two parts of it.

I think the first part is actually that there are some products that legitimately have problems. They’re either massively under-dosing — and that’s maybe a third of the products that we see. So the active ingredient isn’t there, there are some sort of heavy metals or purity issues. And that might be the D or F grade products on the site.

And then there’s really this other group of products that you should worry about quality-wise — I would say the B and C products — where they’re just not highly concentrated. Maybe there’s some famous brand that you’ve always heard of, but like the fish oil is 50 percent Omega 3 instead of 90 percent Omega 3. Or the protein powder is 40 percent protein instead of 80 percent protein. And those are kind of the B and C products.

So those are the two things that you have to worry about: are you not getting what you paid for or are you really being cheated? These are the two types of quality control issues that we really find on a regular basis.

(00:11:13) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. These are the most common things. How would you describe supplement quality? Because I know you’ve got your own kind of internal rating system, where you look through a whole bunch of different criteria.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, I think what we really want to do is start by, it’s really kind of rewarding active ingredient quality and quantity, and starting to penalize for the negative inactive ingredients. And so, as much as possible it’s very, the calculations we try to be as intuitive as possible with it.

The number one factor is going to be the concentration of active ingredient. So it’s going to be the Omega 3 concentration in fish oil or the protein concentration in protein powder. Next, we’ll look at the quality of the active ingredient. We’ll look at the EPA and DHA in fish oil, we’ll look at the amino acid profile in protein.

We’ll look at label accuracy. So we’ll look at how those numbers compare to the label. And we’ll look at purity. We’ll look at mercury and PCBs in fish oil. We’ll look at arsenic, lead, and heavy metals in protein powder. And that’s really it. I think we want to try to look at purity and potency and figure out, ‘Does it work?’ and ‘Is it safe?’.

(00:12:19) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. Thank you for that. So, how do we go about testing these things? What kind of technologies are you using to look at the supplements?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, so it’s really kind of classic analytical chemistry. So we’re looking at chromatography and spectroscopy, like an HPLC or a GC-MS, ICP-MS.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. Could you quickly describe that? I know what you’re talking about, but I think these are terms that the majority of people don’t really understand.

I look at chromatography as basically splitting things apart so that you can look at them. And then spectroscopy as actually doing the analysis. I don’t know if you’ve got a better way to explain it.

[Neil Thanedar]: So yeah, we’re basically separating, identify ingredients, and we’re figuring out their quantities. So an HPLC could actually look at anything from caffeine content or a kind of vitamin content, or it could even look at something like sunscreen content and look at the different sunscreen ingredients.

What we’d like to do, and I think this is a big part of our process, is if we can get a couple of HPLCs in the building and really ramp up our testing in supplements, that will allow us to start experimenting with other types of products that we could test.

And so really we’re looking at, in any of those machines, is we have standards of the ingredients. What are the best quality ingredients supposed to look like? You can run that through an HPLC and you’ll get a curve. Then you can run the product through the HPCL and get a curve and you can see the difference.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. So, when you say HPLC, what does that stand for again?

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. Right, for separating things out.

[Neil Thanedar]: So yeah. I think those are the things where we’re not inventing, really. That’s not our, I mean there are a lot of scientific start-ups out on the market that are truly on the frontier of science. I think a lot of the work we do, there are new methods every year and things are advancing, but for the most part, it’s an established industry.

The testing part is established. I think the part that we’re trying to work on is – how can we test thousands of products. How does it get to a point where we test thousands of products?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I guess that’s primarily about cost?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, it’s a chicken and egg problem, right? Because we’ve got to do the testing before you show up. So we need to, there’s kind of a constant process of kind of testing a little bit, add one more category, bring money back into the business.

And that cycle is really important to us. And the cycles are going faster at this point. We want to be at a point where we can test, instead of 25 products a month, 50 or 100 or 150 products a month.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So, with the approach to testing that you use, do you have to say what you’re looking for? Or does it actually show up, everything that is in the substance? So do you have to pre-decide that I’m looking for mercury, for example, or will you pick up other things in that process?

[Neil Thanedar]: You’re looking for specific ingredients.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay.

[Neil Thanedar]: So that’s the HPLC where you would look at caffeine versus a caffeine standard.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Neil Thanedar]: And I think that’s the part that we haven’t quite, these ideas, these magical devices where you scan your food and it tells you every ingredient simultaneously. That’s truly on the frontier; that’s not science that exists today.

So we’d love to have more information on it. Until then there is, at some level, brute force work being done here. And at some level, we’ve got established panels of ingredients we can look for.

So you can look at all of the heavy metals at once, or you can look for a whole set of carcinogens at once. There’s a whole set of banned substances that you can all do in one scan. There are certain things that we’ve set up, and with everything else, there is a bit of brute force work. Especially with the active ingredients.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So when you say brute force, what does that mean?

[Neil Thanedar]: So you would have to, for example, for a multivitamin you would have to separate every individual vitamin out of there and test them each individually. And it might even be as far as vitamin A is going to be in the product in three or four different forms. So you would have to test each of the four forms of vitamin A individually.

That’s when I start thinking about, that’s truly where we start getting into reverse engineering for active ingredients. Where you need to get down to that individual level because we want our calculations to take that into account. We want to have, if different vitamins A forms have different bio-availabilities, we want to use that as part of the calculation.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So I guess in your process of trying to understand each new area, you plan a new category. For example, fish oil you’ve done, but then you come across something else so you’re like okay, maybe this is a growing supplement or something that people are getting more interested in so we’ll attack this category now.

I guess, first of all, you’re looking at some research to kind of see what the issues are, what kind of things you want to look at. And then you have these standard things, like carcinogens and metals that I’m guessing you’re looking for in most things, just because… I guess if something is made in China, the odds that it could have some metals in it, that’s one of the big concerns.

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s even beyond that. I think, well also almost every supply chain is global at this point. So we just test everything for heavy metals off the top. So those are certain things where it’s just automatic. An ICP-MS is expensive, but it gets a lot of use.

Whereas something like each individual ingredient, I think we have to make a decision on [what to test]. For example, with protein powders, we started with a very simple analysis. We started with just a [unclear 0:17:35], nitrogen analysis. So we were just looking at the total nitrogen content. And then we started looking at total amino acid content, and then we started looking a pre-amino acid content, subtracting pre-amino acid content out.

So there’s a whole range of how we get to the final data. I think the work’s never done because the next thing we’d want to do in protein is get into are there specific amino acid ratio [that are] more bio-available. So could we build into the calculations a system that scores the amino acids? That’s something that we would be interested in doing.

So at some level, there’s this constant improvement that has to happen. Many of the products on our site we’ve tested only once, because we test on a yearly basis and it’s the first year. That’s another thing that’s going to improve the data. So year two or year three, we’re going to get more data, we’re going to see is there any batch to batch, year to year variation.

So all of that stuff is part of our expansion process. It’s part of our growing process where it’s why we purposefully limited it to 25 products per month. That was our case, and we can hold to that. And we can consistently deliver that kind of quality, but we’re not going to go in and say, hey look we have 100,000 products on our site. It’s just not possible to do.

(00:18:54) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, it’s not feasible. It sounds like you’re going to be on a learning curve. Say you did protein like two years ago, you do it another year and you’re like, you know what, last time we learned this, so we can integrate that and we can look for that this time, and that’s going to be important for the new formula.

Is that the process you’re going for with some of the main supplements?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yes. And it’s also, you get a lot of consumer feedback after that, because we might build our quality rankings based on usually very quantitative, what we talked about. Very quantitative factors like concentration.

But then what we need to figure out, and what we’d love to add, is more types of rankings. So there are other reasons or other ways for people to make a decision. And so we used to just have one set of rankings, and we found out that some people weren’t buying the number one.

And we said, hey, why do people not buy the number one? Oh, there are some people who are vegan so that’s not their number one. So we added a vegan filter. Some people were buying products for kids, and so we added a children filter. People were buying by value, so we added a value ranking that’s completely separate value ranking.

And I think in a perfect world, there would be, you could take a test where we would just know who you were, and your perfect LabDoor rankings would show up. And they would be perfectly customized to you. We’re on that lifelong path of getting to the point where we can perfectly customize it to you.

And quality and value and kind of vegan and sugar-free; we’re hitting the major ones right now. And then it just keeps getting better and better.

(00:20:25) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Excellent. And so how accurate is the volume aspect? So you can identify and say that fish oil has DHA in it, or it’s non-oxidized. But how do you understand the actual amounts of this, and how accurate is that?

[Neil Thanedar]: So we’re looking at percentages.

So if you look at a fish oil capsule, it’s anywhere from 10 percent of that capsule is Omega 3, to 90 percent is Omega 3. If you tested the same product again that was at 90, you might see it at 92 or 88.

There might be a little bit of a variation there between tests, but you’ve got a good sense. The product that tested at 90 versus the product that tested at 80, there is a clear separation there.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Sure. So what is the swing, and is that, I mean that could be just due to each capsule, right?

[Neil Thanedar]: We’re taking an average of at least 10 plus capsules. So we’re getting a little bit of a range there.

It’s that kind of a range, so maybe in the 2-5 percent range. Sometimes in certain categories with many ingredients sometimes you see a 10 percent variance. But these things are pretty consistent. Once you put that first test out, you have good data.

And I think that 10 percent variance off of the label; the labels are often very inaccurate as well. So the labels tend to be more than 10 percent inaccurate. So I think what we want to do is as soon as we put that first data point there, you’ve already got better data than you had before.

And now our job is to go in and solidify that. And so there’s a constant tradeoff between ‘do we go to a new product’ or ‘do we test the old product again?’

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So when you’re taking the average, are you taking, say from one bottle you’re taking like 10 capsules or are you trying several bottles? How do you approach that?

[Neil Thanedar]: No, so we’ll want to take it all of it from the same lot. So we’ll try to buy three or four bottles and have it be the same lot.

And so then we might need 50 to 100 total samples because you might be 10 per test or similar. So you will end up using about 100 of those capsules in a round, and save the other 300 just in case a company comes back and questions the data, we need to retest. All of these kinds of things, so it’s important for us to do.

So we’ve got a decent range there. And I think what we found out is these companies are generally doing between two to four major batches of product a year. If you grab any one of those products off the shelf, you get really close on that first test. And then everything after that, we just have to test every year.

(00:22:54) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So you’ve mentioned lots and batch. Are they the same thing?

[Neil Thanedar]: So I think a lot of people would think, I mean there might be multiple lots in a batch. So it’s a little bit of manufacturing lingo.

I think we are starting out, so that’s part of our learning curve as well. We’re trying to get more into how manufacturers work, and how that side of the industry works because I think we jumped in just totally as consumers. And we were just like how can we figure out how to make this data out.

And then what we found out was there’s different, I mean from the industry there are companies complaining about, hey you’re sharing our proprietary blend. Don’t do that. Or, that data is wrong, or our data shows something else. Our internal lab says something else. And there’s a lot of that.

And in the early days I think we almost didn’t have the time to handle all of the information at once, and if we had to focus on one thing it would be consumers. We’d want to focus on the people who are taking the products. But now I think, as we step back and get a little more organized, we’re starting to figure those things out.

How do you talk to companies, how do you manage the system, how do you figure out and return that data back to the manufacturer? If we find something, can we alert them? I think we want to do a better job with that, we want to do a better job of being a part of the entire industry, instead of being this kind of renegade on the side.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Do you get a lot of manufacturers reaching out proactively to you then? Has that happened a lot?

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s a slow, steady pace. There might be a manufacturer a month or something who will come out.

And I think there’s a whole range of them. I think the majority of the complains are honestly like A- companies who…

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. The one’s who really care.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, they really care. “I’m number 8 and I want to be number 1, and here’s why.” And there’s literally 20 reasons why, and five studies attached. And we love that; that’s wonderful. If you do that, our scientists will read all of those studies and we’ll talk about it over a meeting and it’ll be interesting to us.

And if you can convince us, [great]. That’s one of the big things that the protein manufacturers are trying to argue, add an amino acid scoring system. And maybe the ranking will shift a little bit. I don’t think it’ll do very much, but there might be a few products that fall out.

(00:25:05) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So I guess there’s the other subject that some of these products have been around for a long time. So protein is pretty well standardized as a market, and fish oil as well. But of course, then you have some of the newer supplements.

Those must be a bit more challenging because the research can still be evolving, in what the active ingredients are. “We’re not 100 percent sure, but we think it’s this one” kind of stuff.

[Neil Thanedar]: That’s a tough one. I think that is a lot more in our calculations. So the testing is much more straightforward.

So the nice thing is, even if we’re testing a nootropic or something, there would be specific ingredients where even if the clinical research hadn’t completely proven that that ingredient works or not, we could 100 percent know whether it’s there or not. We could at least know that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Because the first thing you’re doing is you’re just comparing the label. The label says it has this, and actually, it has something a little bit different in it. So it’s an easy comparison to start with.

[Neil Thanedar]: That’s easier. The part that we need to figure out, and sometimes we’re staggering that. We might really focus first on the ingredients that have really clear claims.

And now we’re kind of, we are getting more and more into specialty products now. So we are now ramping into testing B complex in glutamine and all of the joint support.

So now we’re going into things that have more complexity or variety. We’re starting to unpack our old categories. So now protein is going to have protein bars, and protein shakes. There’s going to be new categories.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I mean, a protein bar tends to be pretty complex in its makeup, right? It has all sort of ingredients.

[Neil Thanedar]: We want to figure out the protein quality in the protein bars because that’s such an important thing. We’ll start testing vegan Omega 3s in the next couple of months.

So it is that kind of constant process of expanding the existing categories, getting into new categories, and then doing the research on the fly. And we’re finding that in some places there’s not good research.

When you test an ingredient, and you have all the data and then, it’s garcinia cambogia and there’s no great evidence that says that it works. And in many cases, we still try to plug that data into our rankings, and you get like in our garcinia rankings, there’s not a single A grade product on the ranking. Because there’s just not enough efficacy in the calculation to get the score up.

(00:27:15) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So you have five criteria. [First is] label accuracy, which is very straightforward for you guys, you basically just compare. Then you have product purity. What is that exactly?

[Neil Thanedar]: We’re just looking at the heavy metals and contaminants versus upper limits.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay, great. And then the nutritional value, would that fit more into what we were just discussing about garcinia cambogia? How would you say that?

[Neil Thanedar]: Garcinia cambogia. No, nutritional I would think like the RDAs or daily values of the macronutrients.

So that’s what we’re looking at. We’re working on all of these names, and we’ll have to figure out exactly what they are.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Neil Thanedar]: But I think nutritional value, I pour it over the daily value type stuff.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]:Okay, so you compare there. And then you’ve got ingredient safety.

[Neil Thanedar]: So I’m looking at the quality of the inactive ingredients. So what’s the safety risk of the inactive ingredients?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. So if people don’t like aspartame or something in their pills, there you go. And then projected efficacy, would that be going back to our other discussion right now, as in is this really an active molecule?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah. So that’s concentration of active ingredient and the quality of the active ingredient.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay, cool.

Just so people know when they go to your site what they’re looking at and how to navigate it properly. So it makes a lot more sense and they understand where things are at, and how these things are based over time. And obviously, the label accuracy is the thing that they can trust the most from the get-go.

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s really interesting, and I think we look at it that we want to have different people weigh it different ways. That’s another part of our learning curve.

Some people want to be entirely efficacy focused. So it’s just like, give me my active ingredient. And I think that’s really important to people. “I want a 95% pure Omega 3.” And some people are very focused on purity, and purity is the only thing that matters to them. And they’d almost rather take a placebo that’s pure.

And then there’s a group of people who are all about honesty and label accuracy. And I think what we want to do is we have our own weighing system, and I think we’d love that as part of the personalization process.

We’d love to have a process where you put in your own weights for what you think is most important, and the rankings change based on that.

(00:29:21) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Great. A lot of people in the supplement industry have certificates of analysis from the manufacturers. Is this something you get from the companies?

I guess you’re not reaching out to all of these guys, you’re just kind of buying up the products.

[Neil Thanedar]: No, it’s really a retail process for us. It’s an independent purchase.

The A- people will send us their certificate of analysis. And that’s fine. Anytime we’re working with manufacturers and there’s science going back and forth, we’re in a good place.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, cool. So their certificate of analysis is basically the same kind of analysis or something similar, to say what’s in it, that they’ve had done either by their manufacturer or themselves or a third party lab normally. And then they can compare it to yours and say hey, I want to be A+.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, and sometimes it’s the other way. Actually, more often it is a request for a certificate of analysis from us because they want to go to their supplier and complain.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Ah, interesting. So do you think they’ve got false certificates of analysis? Or they just didn’t…

[Neil Thanedar]: Well there’s just so many moving parts in any of these supply chains. So if you’re making a multivitamin you might be sourcing 30, 40, 50 ingredients. And so if you see the LabDoor report and two are off, you know which supplier that is and you can go find out.

And that’s something that’s really interesting data that could help the supply chain and manufacturers. And honestly, we just haven’t found a way to package that data back up. It’s just that we’ve always purely focused on how to get the data first to consumers.

And as we build up more and more data, as we start seeing trends and see more years of data, that will be another type of business that I think would be interesting for us. Because that’s important to us; I think we’d want to be more and more integrated over time.

I could see a place where maybe LabDoor does all of those types of certifications. Instead of an Organic certification and a Gluten certification and the Tested for Sports certification all being different companies. LabDoor is going to have to do all that testing anyway. So if we could somehow say look we’ve already done the testing, here’s the certification, that could be a really interesting thing for us.

We’ll look at every part of the industry in every way that we can help. That’s part of the expansion process, it’s part of how we learn, how we grow, how we provide more value.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And now just to consumers but, like you say, to the manufacturers and the suppliers to improve the supply chain in general. Because it’s not necessarily the brand owners.

He could design a great product and he could ask a manufacturer depending on his due diligence, and [unclear 0:31:59] just to pick up on these things. And the testing given to him might not be his fault, but it’s not exactly what he wanted in the first place.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, I think it’s between that and there are so many things that they’re focusing on. And I think that we want to be the place where if you’re a manufacturer, just focus on making the best product. We’ll help show it to consumers; don’t spend money on marketing, spend money on quality ingredients.

And we’ll give you the data you need. It’s really transparent; we’re really transparent with the A- people about what it takes to get to an A. And we’ll do that with everyone else.

Every company knows, obviously, the reason I’m losing to the number one guy is they have twice as much Omega 3 per gram as I do. Now I know that it’s going to be three times more expensive for me to increase my Omega 3 concentration. But that’s a tradeoff, and they’re going to have to make that equation.

And we would love it if LabDoor was driving so much sales to the high concentration folks that the math eventually worked out, that you should just make higher quality products.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, because you’ve provided more information into the market, and more people are making informed decisions, and thus it becomes more in their interest to raise the quality because their sales volume increases based on it.

(00:33:10) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So what types of supplements have you looked at so far, and as an overview how have you found the general quality of supplements to be? Was it what you expected? Especially based on the articles that all came out last year about testing Walmart, CVS Pharmacy and places like that. There were a lot of issues that were brought up then.

[Neil Thanedar]: I think, well there are a couple of things. So one, we’re about to release glutamine, which will be our 20th category. So if you go to LabDoor.com/rankings, you will see the 19 rankings we have done so far.

So it is more than just protein and fish oil, there’s multivitamins, prenatals. We’ve also looked at vitamin C and D, calcium, magnesium, and zinc. We’re trying to go through category by category of the most popular.

And so under that list of the top 20 are the next 50 that we’re looking at. And those, really, consumers go in and vote on what they want to see next.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Oh. So you’ll do that, if people are like, “Yeah, I want this reviewed.”

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah. LabDoor.com/rankings.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay, and they can vote for something new that they want ranked.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yup. And so there’s a whole bunch of categories in there. We’re just trying to grab them as quickly as possible.

So some of the most popular ones on there like glutamine and B complex and glucosamine are already in the lab. We’re already working on them. And just keep voting. Basically, you’ll get an email when that category is available.

What I’m going to try to do is over the next year or so finish those 50 categories. Really go through and say hey, in the supplement industry you can really come up with any major product and LabDoor will have it. Have at least one set of data on it. Just enough to get you in.

And I think once we do that and really get the lab fully up and running and instead of 25 products a month we really should be doing 100 plus product per month. That’s when I would say maybe we’ll look at other categories.

Maybe we’ll look at food and beverage, maybe we’ll look at meal replacement. I mean, we’re already kind of there. Protein bars are already starting to touch meal replacement and functional foods. Even baby products, like baby food and baby formula, are really on the edge of being a supplement; they’re manufactured in very much the same way.

And so any of those types of things we’d love to be in places where you feel like there’s some uncertainty. If you feel like, I don’t know what I’m buying, that’s enough for LabDoor to jump in.

It doesn’t necessarily need to be the supplement industry where you get data every week saying something goes wrong. I think it’s even a case where you are buying baby formula and you have no idea what’s in it. At any point where there’s any of that kind of insecurity, you should look to places like LabDoor to get some science and data, and make that decision with more backing.

I actually don’t think that the, I want to try to make sure that the supplement industry doesn’t get all negative stories. Really that’s where it’s starting to go, it’s really kind of pushing it to a lot of negative stories. And that’s not really our market. You’ll see that LabDoor is not the person driving a lot of those stories.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Sure. I mean, what do you think of the market? You’ve got the data on nearly 20 categories now. Where would you say it’s at? If you had to explain in objective terms, where is supplement quality currently at?

[Neil Thanedar]: I think there are about three even groups of companies.

There are a third that are doing a really great job. And those are basically the A products in the market.

There is a third that are like the B and C products that are just not worth it for the money. And those are usually the guys using brand or marketing to sell products. And then you’ve got the D and F…

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: When you say brand or marketing, could you give an example of that, maybe naming a specific company? But what does that mean to you? Brand or marketing?

[Neil Thanedar]: These are companies that I’ve literally looked at some of these companies that have, first the head of R&D works for the head of marketing in a lot of these companies.

You’ll see these companies haven’t made significant investments in R and D but are spending 20, 30, 40 percent of their budget or more on marketing. And these are companies that are truly spending more on marketing as a percentage of revenue than they are on the products themselves.

And you see that in the data. And those become the B and C products that are actually usually, more expensive than the A products. We’re finding that there’s really no correlation between price and quality. There’s just none in this market.

There are people who are in the middle group who are just medium quality for high price.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So you’ve got some products which are brand driven. They’re a premium brand and have put a lot of good marketing behind it, but actually, the product doesn’t back it up.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, that’s the second third.

And I think the third is honestly the D and F grade products, where people are honestly cheating. There are, and it’s different by different categories.

Something as simple as a creatine product you usually don’t have to worry about as much. It’s just creatine in a bottle. There are fewer things that could go wrong. Those products, maybe 5 or 10 percent of products, have problems. But there are things like garcinia, 70 percent of products have problems.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow. So it really does vary a lot by [category].

So creatine has been around for a long time, and it’s extremely standardized. So I imagine there’s a bit of market development. There must be so many manufacturing facilities now that the technology is well standardized at creating creatine and everything, so it’s a little bit easier.

And it’s also something very straight forward. It’s not like it gets damaged easily, like fish oils and so on. So yeah, I guess each category can be quite different.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, so each category is quite different. Overall, it’s about what we need to do is try to get people to the top third as much as possible. If we can do that, if we can really help you focus when you’re in the store.

Because that’s what’s happening in the store. There are 100 fish oils. And how are you picking with 100 fish oils? And I think that’s why the branded marketing thing works so well.

When there’re 100 fish oils, you see the brand you recognize and that just makes that purchase easier. And what we want to do is say, what if those 100 fish oils were instead ordered from one to 100 in some sort of other system based on science?

(00:39:15) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, excellent. A couple of questions. I realize you probably don’t want to name companies, but I’m interested in the Trusted Science brands, the ones that look like they’re doing research and backing it up with content like Thorne Research, Life Extension. People tend to trust these kinds of brands.

I don’t know if you’ve looked at those types of brands. Not necessarily those guys, but similar ones which are putting out a fair amount of content on their sites, and they talk about their research. Do those tend to have reasonable quality?

[Neil Thanedar]: We haven’t tested as many of those yet, and I think the reason why is because our initial way of picking the most popular products by category was to use online best-seller lists. And the Thorne and the Life Extension are usually sold through doctors so we missed that in the first round.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Probably a bit more expensive for most people as well. That might be a smaller market.

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s more expensive and just in different channels.

We’d like to prove that. We’d love to test those products and see is there really a price and quality correlation there. Because otherwise, industry wide there is zero price correlation. And there are honestly categories on our site where literally the cheapest product in the category is the number one in quality.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Wow.

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s amazing. It doesn’t work [unclear 0:40:29] maybe in handbags or cosmetics. So these are the types of industry where that works, right?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Could you give us an example? Is that something like creatine? Where it’s very simple?

[Neil Thanedar]: It might have been creatine. It might have been something like creatine where the people who were really trying to jazz it up with the fancy box, and five artificial sweeteners and not enough creatine, those are the people who are expensive and at the bottom.

And vice versa; the people who just throw 100 percent creatine monohydrate in a bag do pretty well.

(00:40:58) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Cool. Okay, so we talked about the price correlation, and that there isn’t much, which is interesting. You looked at online reviews from consumers on Amazon as well, I noticed just recently. What were your results there?

[Neil Thanedar]: Same thing. Zero correlation. And what we might need to figure out is they might be answering totally different questions. The user reviews might be totally answering the qualitative question, and we’re answering the quantitative question.

And first of all, there are certain categories of supplements, like a multivitamin for example, where other than pill size there isn’t that much qualitative that you need to worry about. You’re not taking a multivitamin like, oh I feel better today.

There’s not that much qualitative to do. These decisions should be more quantitative. They should be more scientific. And so the thing we try to talk about as much as possible is for most of these categories we should be letting user reviews go and really be focusing most of our energy on scientific reviews.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, well unfortunately, they’re not around everywhere. You’re working on it, but it can be hard to come by.

I used to use Consumer Lab Reports, which is the other company that was doing it. And then you guys came along, and it’s a free service versus a paid service, so it helps me out that way.

(00:42:08) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: What I want to bring up, I don’t know if you’ve seen this new company, which is kind of trying to position itself right at the top of the supplement industry which is Elysium?

[Neil Thanedar]: I’ve seen that, yes.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: With their anti-aging. And they have a scientific board of directors.

So they’ve really tried to go more the scientific approach that we should be trusted, we’re using a pharmaceutical grade production process. We have a scientific board of advisers of some of the top scientists in this area in the world.

I found that was really interesting and really encouraging in terms of really taking a step up. And it’s got VC funding. So it’s a completely different business model, really.

And I guess it’s only been possible now because of the size of the market, where they can now have a VC driven model where they can go and get top scientific advisers on board, sometimes Nobel prize winning guys to be able to raise the standard a lot.

So, it would be interesting if you help with your work to promote that kind of activity as well.

[Neil Thanedar]: Absolutely. I feel like guys like that are the new generation of the Thorne and Pure Encapsulations. And there are more people like that. I think honest companies really try to do that not just in supplements but in cosmetics and household products.

So there are a lot of places where there’s renewed interest in that kind of high quality and direct to the consumer brand. And I think that fits really well with where LabDoor is. I think we want to, we need to get to a place where that product is in a category, versus the other people.

And that would be really interesting. There’s now food test on some of those same ingredients, for example. And there are a lot of generic manufacturers who have the same ingredients as Elysium does, but there’s an issue of do you trust the generic manufacturer.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It’s interesting, because I looked on Amazon, of course, for the ingredients — because they’re being transparent about the ingredients, which is another thing. Not all companies will tell you exactly what it is in the product.

Some companies you can ask them for their certificate of analysis. A lot of consumers don’t know that, but you can just contact them. And sometimes they’ll give it to you. It depends on their policy. And sometimes they’ll say sorry we don’t hand out that for propriety reasons. Or whatever.

So there are a fair number of certifications out there. I don’t know if you’ve looked at any of these. Sometimes we see these stamps on products and we don’t really know what’s behind them, a lot of the time. Have you looked at any of those?

[Neil Thanedar]: We’ve looked at it a little bit.

So, I think my general issue with certifications is there are many of them and consumers don’t really understand what they all mean. I worry that in a situation where if you give too much information, it’s an overload and actually doesn’t get paid attention to.

So that’s one of my issues with certifications. What we’d like to do at LabDoor is to try and figure out if there’s some way to get beyond a certification, beyond a pass/fail system and get to is the product really good.

Because there are two different parts to this. There’s the part where hey here are the third, or two thirds of the products that are bad. That’s fine, but I think our business is really dependent on can we help you make a good decision. Can we help you get into the good third?

And so what we need to do as much as possible is find that way of saying I’m just highlighting the good products. I think for us that’s really we have to keep focusing on it that way. And so I want to, as much as possible I would like that not to be certification based.

I think if we wanted to say, look it’s not about whether it’s organic or not, it’s about what’s the quality of the product. And in many cases, just because it’s organic doesn’t mean it’s pure, in many cases, organic products can catch a lot of heavy metals.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, that’s a good point.

[Neil Thanedar]: So all of those things we don’t want to get into, we don’t want to outsource the decision to that single certification. That you really should be having your decision on a holistic approach to the product.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. I guess whether it’s organic or not, that’s kind of a philosophy. But at the end of the day, it’s the pesticide resides and the heavy metals that people are really interested in, a lot of the time.

[Neil Thanedar]: It’s very much like the filters, to me. So, if you want to have a vegan filter, or a sugar-free filter, or an organic filter, a non-GMO filter in your life I think that’s fine.

I think that’s just a fundamentally different decision criteria that’s almost like the quality and value ranking. We’ll let those things be, let them cross, and that is useful as a filtering tool.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Also, I think we kind of covered this, but have you come across instances where the certificates of analysis have been different to what you found?

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah. What we’ll do is there’s a kind of a standard process.

So if we have our testing and our certificate of analysis, a company comes with their own, then we will go to a third party lab and we will get testing done there.

And the idea is basically if the grade goes up, we’ll pay for it. If the grade goes down, they pay for it. And that’s it, right? It’s just I think that is, we want to figure out a system where it’s just [fair].

I mean, at any given point we’re defending 700 products, and soon we’ll be defending thousands of products. And so we want to be able to say at some level we want to be the referee and we understand that not everything is going to be 100 percent perfect. And we’ll just be open to it.

And if you think that something is wrong, challenge us on it. And challenge us with scientific data with a certificate of analysis and look we’ll test it. We can always test more. That’s possible. The thing we can’t do is kind of get into shouting matches with companies.

(00:47:23) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, sure. So in terms of, to give people an idea, how often does that come up? Does it come up a lot or is it relatively rare?

[Neil Thanedar]: I would say it’s less than five percent of the companies who will ever kind of come and talk to us.

And I think a lot of people indirectly come and talk to us. We’ll get emails from their customers complaining, or things like that. There are all kinds of side things.

I think it’s something where there are some very passionate people on the manufacturing side of the industry, and I think we’ve tried to be really open with it. I think it’s important for us to actually be talking to more of the industry.

I actually should be going – and I’ll do more of this — is going and travel, spend time at supply side conferences, where people are actually talking to the manufacturers. I need to do that. And I think that’s something that as we get bigger I should be talking to half or more of the industry.

Because I think if LabDoor’s data gets back to the companies, it’s going to be good for the industry. It’ll have rapid feedback. You’ll have feedback from consumers and from the lab. Both of those things are incredibly valuable for manufacturers, and it’ll make the products better.

(00:48:30) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So we’re talking about the technologies you’re using are relatively standardized now. They’ve been around quite a long time. I think they’re currently getting better in terms of cost, right? They’re expected to get cheaper over the next years. That was just a training I was at recently.

But I was just wondering if you think there’s some variability. So say if they did come with another certificate of analysis and then you went to a third party lab, how much variance does there tend to be between labs?

Because just in my own testing, I test a lot of different things, and there’s a fair amount of variability between the labs, unfortunately. We’re still in the middle of a kind of, I guess it’s mostly the processes and ironing out all of these things, and some of the technologies are getting more mature over time and more stable.

For these particular technologies, how stable would you say they are in the accuracy?

[Neil Thanedar]: You’re getting good data out of it.

I think even in a situation where there’s a 10 percent lab-to lab-variation, firstly there are different labs and I think [with] the labs we use we’re seeing some 10 percent variation. And in many cases, we were talking about 2-5 percent batch-to-batch variation.

So even different labs, different product in a different batch, we’re seeing pretty similar results. And that’s just some of these products, and it’s with the established companies. The thing that we’re finding is there are some companies where the product is vastly different, from category to category. There are certain things where I worry less about that.

I think what we need to do is build repeat testing into the model. Because any sort of calculation like this the confidence goes way up when you get the second, third and fourth test. So I think that’s where we’re at right now.

The first test is good data, and it’s important for consumers to get it. And then every other test, the second, third, or fourth, you get a lot of increase in confidence, and then you just have to be consistent. Then you have to get on your yearly or every-other-year basis, and we’ll be humming along normally.

And so I think for us, LabDoor Year 5 out of a 10-year process of really kind of stabilizing everything and having a fully operational machine. And then we’d want it to just automatically test products.

Like every month people request new products, we test it. We’re automatically getting into new categories, we’re automatically maybe thinking about new ways to rank products, we’re getting deeper and deeper into personalization. But it’s a very, it’ll be a very consistent improvement process.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Have you got plans to retest any categories yet? Or are you doing your first retest with any category yet this coming year, or is it going to be a little way off yet?

[Neil Thanedar]: No, I think, well yeah, we’ll be doing retesting. I think we’ll get multivitamins retested next year. There will be whole categories.

We want to be, in 2017 if we can get to the point where we are not just, we’re marking the dates on when we tested it last and predicting when we’re going to test it next. And really as much as possible, say the popular categories are every year, the less popular every two years.

And again, just like everything, we can start shrinking those things because right now we’re on basically two-year testing cycles. And we want to push everything to yearly testing cycles.

And it would be great to say that LabDoor 2016 protein data is this and 2017 protein is this, and let’s see the trend of which brands have been consistently at the top and consistently at the bottom. Those are all things that it is about, we need more lab capacity. We need more testing.

We’re going out and we’ve raised venture capital. And so that’s a big part of this process and a big part of the reason why we think we can do 100 products a month next year instead of 25 products per month. That’s a big part of that too.

That’s how we’re going to get there. We’re going to have to get there 100 products a month at a time. We’re not going to be able to download the database of 100,000 products because that doesn’t exist.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. It’s step by step. You’re building lab capacity basically over time and trying to make sure it’s monetized. So it’s a step by step process. Great.

(00:52:19) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Now let’s talk about some specific case studies from some of the more interesting takeaways. What have been some of the worst lab results you’ve seen in categories?

[Neil Thanedar]: I mean, the garcinia cambogia was still the worst category we ever saw. There were fully 70 percent of the products that did not have the labeled active ingredient.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So they had zero, had nothing?

[Neil Thanedar]: No, they had less than their quantity, but they had…well we’re talking about 10 percent or less than the label claimed, that kind of thing. For most of those products. To the point where it’s essentially nothing.

And what that is is that was a lot of fly-by-night, they are usually selling on Amazon. This is something where you can just spin up a brand out of nowhere, white label it, throw it onto Amazon and there’s no check. There’s nothing between you.

And then theoretically, there are user reviews between you and that product, but then these companies buy user reviews too. And so that’s it, there’s literally nothing between you and this product hitting the market.

And so we’ve seen, the cool thing is you go and look at a lot of those affiliate links and they’re broken, which means that the products have come off of Amazon, so not being sold anymore. And so there’s some sort of cat and mouse game there.

I’m sure some of them have spun up and made new products, and we’re going to have to go chase those down. But at least in some of those cases, we’re seeing that they’re gone, they’re not there anymore. And I think in those cases we do our job, when we show people what’s right and wrong. I think we’ve done a good job.

I think there are categories like that where 70 percent of products fail, there are categories like creatine where 10 percent or fewer products fail. And then there’s kind of the in-between zones where with fish oil you’ve got about a quarter of the products have rancidity issues. And so we’re filtering that, and that’s part of purity; that’s a part of our purity score.

So we’re seeing in different categories there are issues, but I think in the other categories they’re more like, hey there’s this like, half of the products that you need to avoid. Or there’s 30 percent of products or 10 percent of products you need to avoid. It’s still worth checking. Right?

In any of these situations, it’s still worth checking, but that’s the range we’re at. Somewhere between 10 and 70 percent you’ve got to worry about.

(00:54:21) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Excellent. So, as you were talking there, I kind of took some guidelines or rules away from the situations you brought up.

Do you have any guidelines in your mind from the research you’ve done so far, on like if there is no data, having been through your research process, have you seen any patterns where you’re like, okay instead I’d use this heuristic to decide which product to buy, if I don’t have access to the data right now.

[Neil Thanedar]: We’re not seeing very much brand correlation. There’s not a ton of brand correlation.

One thing we find is that companies that only make one or two things do really well. So like a company that specializes in probiotics does a really good job in probiotics, but actually has a B- multivitamin or something. Those types of things happen a lot.

And so you have a protein specialist or the creatine specialist that does really well there; fish oil is the same way. So think about that. I think that might be one thing to think about, people who are specialists.

And then really other than that, send us the link on LabDoor and we will add it to our site. I think we need to test those products. We’ve had the luxury I think a little bit of kind of growing quietly. I think a lot of people are just learning about us five years later.

And we did that on purpose. And we did that very, kind of fundamentally we said we’re going to just focus on one category. We won’t go to the press saying, hey LabDoor is this great company, we’ll say hey look at LabDoor’s fish oil data, or look at LabDoor’s Vitamin C data. Look at LabDoor’s multivitamin data.

That part of it I think we’ve been focused on just, come listen to us about what we know. We’ll be an expert in certain things. We’ll be a destination in one category at a time.

And now I think we’re at a point where we need to move faster. And I think that’s why we’ve gone and raised more money. We are kind of going in and buying HPLCs and bringing them into the building. We’re buying auto-samplers. All this kind of stuff to make things go faster.

And so at this point, if you can find things that are specialty products and you trust them, take them. Otherwise, I’m really at the point where I’m waiting. I’m actually saying, well I’m thinking about taking curcumin, but I’ll wait six months until LabDoor tests it.

I might be in that process, I think because I know curcumin is going to be one of many other categories that are going to be… You’ve got an extract that certain companies, certain products are going to really pull a lot of heavy metals out of that extract. There are different extraction processes.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. There are some like that which are going to be challenging, for sure. Because it comes from turmeric, and turmeric can come from all sorts of places. So you can tell that one is going to be a complex one.

[Neil Thanedar]: And that reminds me of something like Ginseng, where the ginsenoside content you can look at. Ginseng is different than the active ingredient, and so you’re not always getting the same extraction. And it’s not consistent. And so in cases like that, I would basically say wait. And that’s how I do it. I wait until LabDoor has some data.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And you’ve got the inside guide to that. Okay. Great.

(00:57:20) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: The other heuristic I was thinking of was you were talking — because I’ve seen this a lot in Amazon — is you have these one product wonder companies, where they basically just make one product. And I think they just pop up.

There’s a new fat loss supplement that they just kind of jump on board. And you see that this company otherwise doesn’t seem to be anywhere or doing anything, but it’s just made this one product. Even it’s website sometimes isn’t great.

But on Amazon they’ve got thousands of reviews, and sometimes they’re at the top of the category. And you’re like what’s going on here? And often they’re giving away products for reviews, and they’re using a whole bunch of marketing tactics to establish themselves there.

But if you look a bit more into the company they don’t have a strong background and they’re just going to come and go. So that’s one of the things I’ve also noticed a little bit that might be worth thinking about.

[Neil Thanedar]: Yeah, we see those a lot too. I think LabDoor is really meant to replace heuristics with kind of a scientific method as much as possible. And I think that’s just really what, bringing us all the way back to the beginning, it’s really what motivated the idea of LabDoor at the beginning.