In this episode we continue our discussion of the microbiome that we started in Episode 9 and continued with Episode 37. Today we try to help you navigate the confusing field of microbiome testing companies and discuss the pros and cons of different technologies.

Examples and lessons learned from our own testing will give you an idea of how a microbiome test can help you make decisions about your health. Finally, we discuss what we think the future of microbiome testing holds.

– Richard Sprague

Long-time software executive Richard Sprague discovered his love for science through microbiome self-experimentation, studying questions like “Can I improve sleep by feeding certain gut microbes?” or “What is the impact of a gut cleanse on my gut bacteria?”

Formerly “Citizen Science in Residence” at uBiome, a biotech company, microbiomics is of particular interest to Richard because it is easy to get access to a lot of raw data that let non-specialists like him make interesting discoveries at the cutting edge of medicine and science. Richard shares his experiments and insights on his Medium Publication called Personal Science and the Microbiome and his blog.

The episode highlights, biomarkers, and links to the apps, devices and labs and everything else mentioned are below. Enjoy the show and let me know what you think in the comments!

What You’ll Learn

- Why is the microbiome interesting (5:40).

- Microbiome testing is now more accessible to the public (7:45).

- Different technologies for trying to understand your gut and what’s going on there and the pros and cons of these technologies. Technologies discussed include: Cell culture, PCR, 16S sequencing, metagenomic sequencing (9:02).

- What is the different between a different bacterial strain and a different species and why this distinction is important when analyzing your microbiome (17:40).

- Cutting edge new technologies to understand your microbiome better: transcriptomics, which looks at what genes are active, proteinomics which looks at the actual proteins and metabolomics, which analyzes metabolites (20:10).

- The reasons why the results from different labs are different (27:30).

- The different labs doing microbiome testing and compare notes on the ones they used (33:13).

- How glucose response and the microbiome are interdependent and knowing more about your microbiome might allow you to predict your body’s glucose response to different foods (51:26).

- The labs at the bleeding edge of transcriptonomics (57:29).

- N=2 experiences with the labs used and how they interpret and compare the data they received (59:24).

- The effects of his ketogenic diet on his microbiome (1:02:44).

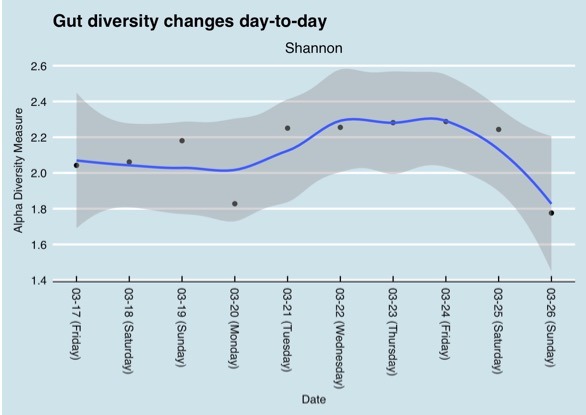

- Discussion of gut microbiome diversity, day-to-day variability and individual difference in the microbiome (1:15:54).

- A self-experiment he has done to try and change is microbiome taking a probiotic and the effects of traveling and eating different foods on the microbiome (1:20:15).

- A way to change the nose microbiome using kimchi (1:22:01).

- Advantages of a varied diet over taking probiotic pills to change the microbiome (1:24:06.)

- High-level thoughts and recommendations about using different microbiome tests (1:28:34).

- Why everybody doing lab tests should try to get the raw data from the lab (1:36:30).

- Discussion of what future technologies and applications will useful to get even more information out of the body’s microbiomes (1:38:23).

- Improvements that would provide better data and insights from microbiome testing (1:41:44).

- How travel impacts the microbiome (1:47:03).

- Where to learn more about the microbiome (1:55:42).

- Information about what Richard is tracking and his interest in traditional foods and medicine (1:57:37).

Richard Sprague

- Richard’s personal website: Short life & career summaries of Richard plus articles about his microbiome self-experiments.

- Airdoc: Richard’s latest venture, a AI-based chronic disease recognition system.

- Richard on Medium.com: Richard is a top writer on health on Medium where he chronicles his near-daily microbiome experiments.

- Richard’s Twitter

Recommended Self-Experiment

Use Kefir to Change Your Microbiome

- Tool/ Tactic: Richard found a real noticeable difference in the microbiome after drinking kefir, in particular a couple of microbes that he did not have before he started drinking kefir and that he has now. Interestingly, one is associated with recovery from Crohn’s Disease. See Richard’s academic pre-print paper.

- Tracking: to track the effects of adding fermented food like kefir to your diet you need to get your gut microbiome tested before the start of the diet and several weeks or months later.

Kimchi for Sinusitis Treatment

In sinusitis sufferers the sinus microbiome is out-of-whack and the probiotic Lactobacillus Sakei is missing. L. Sakei can work as a sinusitis treatment if put into the nostrils. Kimchi is a natural source of L. Sakei. To experiment with kimchi to treat sinusitis Damien recommends the following:

- Put a teaspoon in a container with kimchi and scoop up some of the juice.

- Dip your finger into the liquid and put your fingers up both nostrils spreading the liquid.

More information on how to apply kimchi juice to treat sinusitis can be found here. The scientific paper underlying this approach is also available.

Tools & Tactics

Diet & Nutrition

- Fasting: Fasting interventions can potentially change the microbiome. In this episode it was discussed as a tool or experiment in particular for any chronic issues/ unidentified health issues that no one knows how to solve.

Sleep

- Good sleep is essential for the body. Richard experimented with potato starch to boost his bifidobacterium levels. The result of his self-experimentation can be found in his blog. Although this approach did not work for him, other people have seen positive effects and he recommends that people with problems sleeping try potato starch.

- Damien is experimenting with three different approaches to improve his sleep:

- 10,000Lux SAD (seasonal affective disorder) light. Using this light for two hours every morning simulates strong daylight. This approach has worked for him and his theory is, that the strong light in the morning is a way of resetting his sleep cycle. SAD light use to improve sleep and prevent daytime sleepiness is discussed in this study.

- Going to bed really early also helps him to maintain a solid 7 to 7.5 hours of sleep per night. He now goes to bed by 9 pm.

- Taking a glycine supplement to reduce night wakings.1,2

Tech & Devices

- 10,000 Lux Lamp: Lamp that replicate strong sunlight. Damien has been using this in the morning to reset the circadian rhythm and as a result improve sleep quality. These lamps are designed to be used with Seasonal Affective Disorder, by providing sunlight in dark months of the year.

- Sleep Tracking Devices mentioned include:

- Zeo: A popular fitness tracker that went bankrupt due to issues with its business model.

- Fitbit: This version of the FitBit integrates sleep tracking.

- Oura Ring: OURA is a convenient wearable ring that has become popular over the last year. The company is currently participating in studies to understand the accuracy of its sleep tracking. Damien uses it to track sleep duration only – the base metric.(Note: If you’re looking at buying this discount code gives you 75 Euros off “TNBBJDQX49J”).

Tracking

Biomarkers

The biomarkers discussed in this episodes are strains or species of gut bacteria that are part of the microbiome. Tracking these biomarkers require a microbiome test.

A good best practice is to get a baseline test followed by tests over time, especially if you make changes to your diet, travel or experience health issues, to see how the microbiome tracks.

The four major groups of bacteria are Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Bacteriodetes. Changes in the abundances of each of these groups often associate with many health conditions.

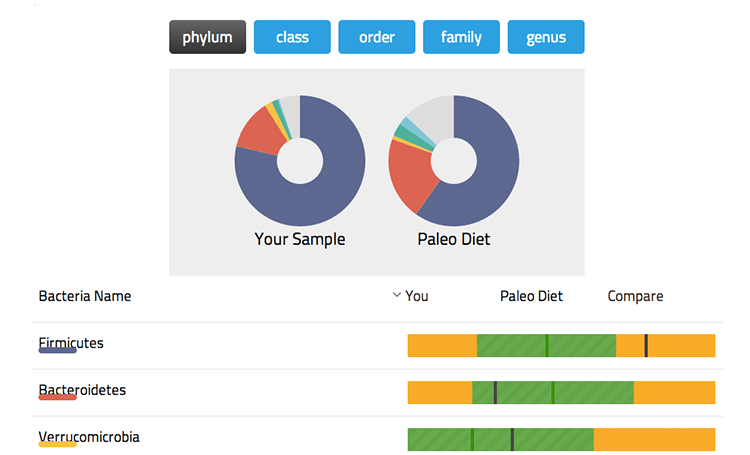

- Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes: are both key players in regulating gut metabolism, and are critical in understanding metabolism dysfunctions. See: “Diet–microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism” Nature 2016. The ratio of firmicutes to bacteroidetes from different lab tests was discussed, and has been discussed in the literature, but Richard is wary of relying on a single test, noting that his own ratio is highly variable day-to-day.

- Bifidobacterium also known as Lactobacillus bifidus are ubiquitous inhabitants of the gut, vagina and mouth of humans. They are found in fermented foods like yoghurt and cheese. Bifidobacteria are used in treatment as so-called probiotics, defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. This scientific paper published in Frontiers in Microbiology summarized the current understanding of the health benefits of Bifidobacterium.

- Spirochaete is a phylum of bacteria that contains many pathogenic species, including Borrelia species that cause Lyme disease. Testing for these pathogenic bacteria can reveal important information about one’s health. Damien put together a paper describing how one could use uBiome’s 16S rRNA microbiome sequencing as a pre-screen tool for Borrelia.

Lab Tests

Microbiome Labs Overview

With a number of different labs out there offering microbiome tests it can be difficult to decide which company to use or what the upsides and downsides may be. The table below provides an overview comparison of the different characteristics of each of the labs including.

| uBiome | AmericanGut | AtlasBiomed | DayTwo | Aperiomics | Viome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFFER | Cost | $89 per test | $99 per test | £274 ($379) per test | $329 per test | $781 per test | $399/ year |

| Breadth of Testing | Gut, Mouth, Nose, Skin, Genitals | Gut | Gut + DNA (+ Metabolomics/ Blood Markers) | Gut | Gut, Blood, Urine and Oral Swabs | Gut + Metabolism (blood glucose regulation) + Body dimensions | |

| Service | N/A | N/A | N/A | Nutritionist consultation included | N/A | N/A | |

| Geographies Served | International | International | UK & Russia | US Only | International | US, UK & Canada | |

| Year Started | 2012 | 2012 | 2017 | 2017 | 2017 | 2017 | |

| TECHNOLOGY PLATFORM | Sequencing Type | 16S | 16S | 16S | Shotgun | Shotgun | RNA |

| Information Depth | From Phylum to Genus | From Phylum to Genus | From Phylum to Genus | From Phylum to Species and Strain | From Phylum to Species and Strain | From Phylum to Species and Strain | |

| Type of Information | Metagenomics (What genes are there) | Metagenomics (What genes are there) | Metagenomics (What genes are there) | Metagenomics (What genes are there) | Metagenomics (What genes are there) | Transcriptomics (What genes are expressed/ active) | |

| DATABASE SCOPE | Coverage | Bacteria | Bacteria | Bacteria | Bacteria | Bacteria, Viruses, Parasites and Fungi. | Bacteria, Virus, Parasite and Fungi |

| BENCHMARKING DATA QUALITY | Benchmark Data Quality/ Scope | Likely largest database currently | N/A | N/A | The Weizmann Institute studies included over 1000 Israeli participants on glucose regulation and the biome. Currently have study underway in U.S. | Large whole genome database covering over 37,000 microorganisms, 7500+ of which are known pathogens. | Very early stage - likely most limited currently |

| OUTPUT YOU RECEIVE | Actionable vs. Informational? | Informational | Informational: Detailed reporting. | Informational: Limited information (only family/ genus level reported) Actionable: Many specific recommendations | Recommends Actions: Rates each food according to your glycemic response | Highest level of granularity of species reported. | Recommends Actions: Rates each food |

| Transparency of Recommendations | N/A | N/A | HIGH: Includes reasing and study references for most recommendations | MEDIUM: Doesn't Explain Recommendations, but can assume comes from Weisman work | HIGH: Discussion with researchers. | LOW: No information given on which various inputs explain outputs or why | |

| Raw Data | Yes | Yes | No (planning to add?) | No (but planning to add) | Yes | No (No plans to add) |

Note: This is a high level analysis of the current technologies and labs on the market which are primarily focused on metagenomics. There are others that have yet to emerge commercially but will eventually create a broader and more complete landscape and understanding of the biome. These include metatranscriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other meta data.3

Microbiome Lab Tests

- uBiome Explorer test: Richard used to work for uBiome as a citizen scientist. They use machine learning, artificial intelligence, statistical techniques, and a patented precision sequencing process based on 16S rDNA sequencing to analyze the microbes in a sample.

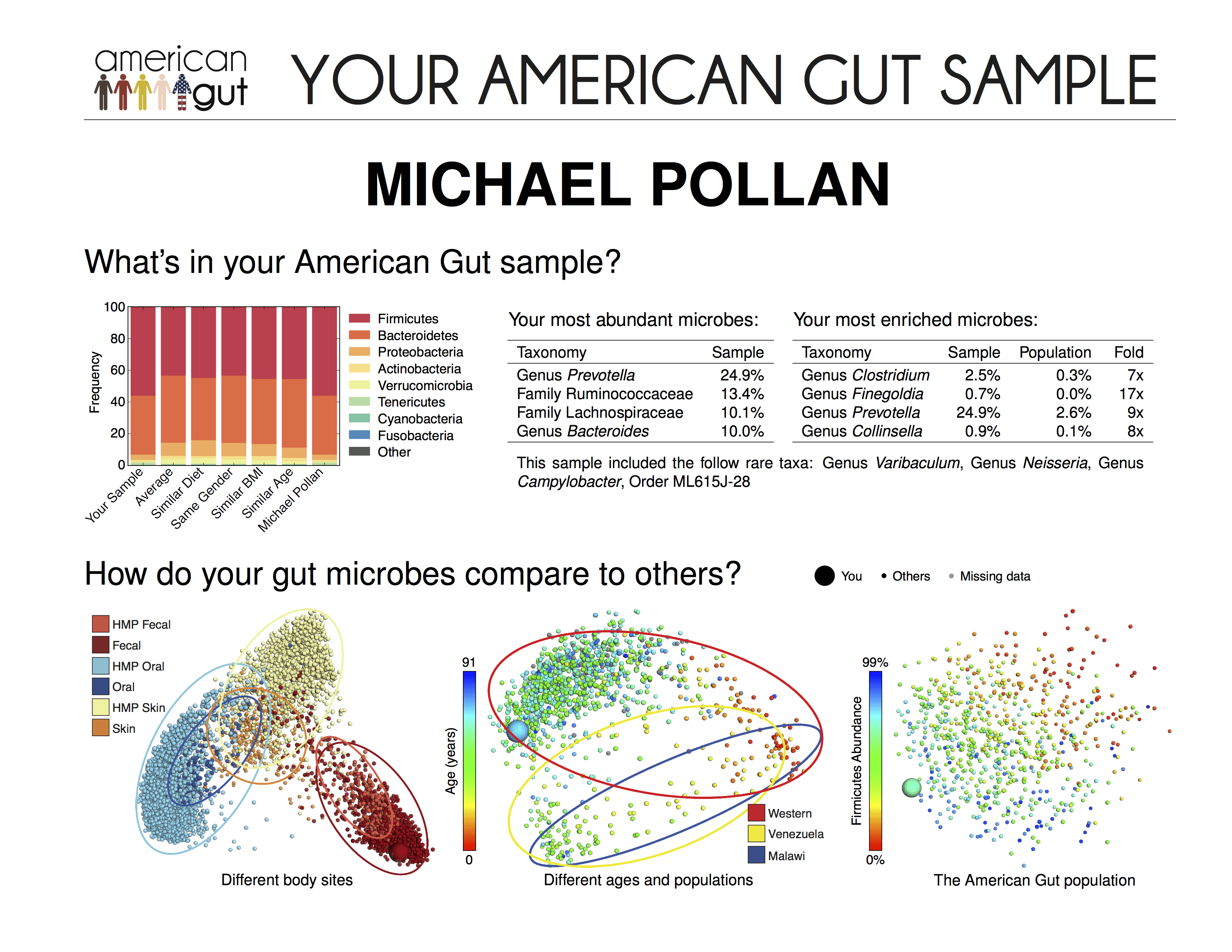

- American Gut: this project is run out of Rob Knight’s lab at UCSD and is one of the largest microbiome research labs in the world and the world’s largest crowd-funded citizen science project in existence. Anybody can join the project by making a donation.

- Atlas BioMed: a UK based company does DNA and microbiome testing based on 16s rDNA sequencing.

- Doctor’s Data Microbiome Testing: a clinical lab performing specialized testing.

- BioHealth GI Screens: a company providing functional laboratory testing, including testing of the gut microflora.

- Aperiomics: identifies every known bacteria, virus, parasite, and fungus in samples. Specializing in identifying pathogens and solving complex clinical infections.

- Diagnostic Solutions GI Map: microbiome testing based on PCR technology.

- Gencove: offers DNA testing to explore ancestry and tests the microbiome of the mouth.

- Arivale: tests the genome, blood, saliva, gut microbiome and is taking lifestyle into consideration.

- Viome: Analyzes the gut microbiome to help improve health, weight loss and wellbeing. Viome offers an annual plan that includes a microbiome test.

- DayTwo Microbiome Analysis: provides personalized nutrition based on the to maintain normal blood sugar levels. The company studies individual metrics and gut microbiome and translates their findings into actionable insights. Richard’s review of DayTwo can be found on Medium.

- Thryve Gut Health Test: assess gut health using 16S sequencing and provides personalized probiotics kits.

- GI Effects Comprehensive Stool Test and GI Effects Microbial Ecology Profile Test: these are tests available via Genova.

Analysis of the Different Labs

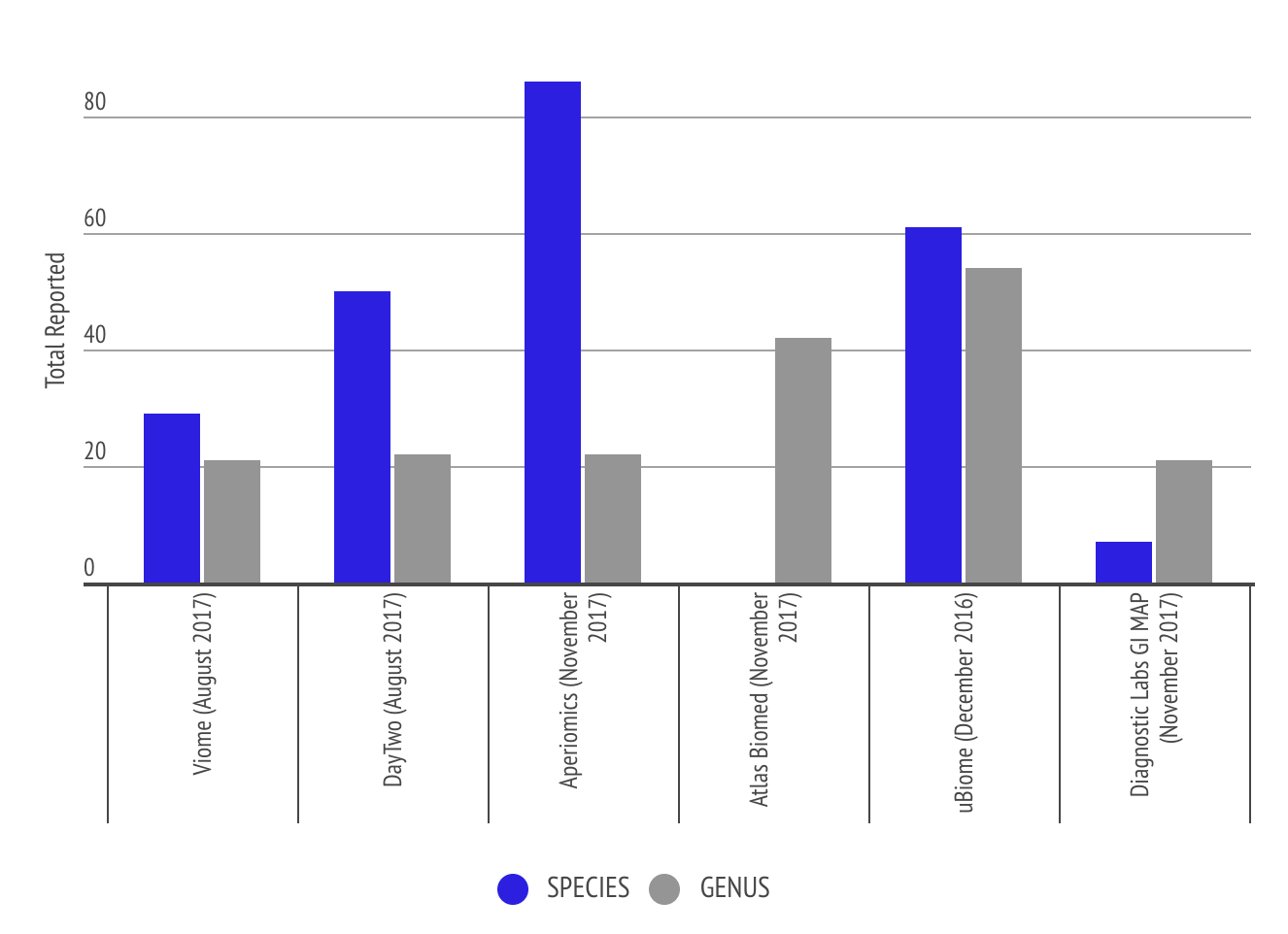

Granularity of Output from the Labs

This graph shows the level of granularity of information different labs provide to the customer in terms of number of species and genus. Some labs like Atlas Biomed only report genus level. The comparison shows that Aperiomics is able to identify more species due to the higher depth of sequencing the lab uses.

Analysis and Graphs from Richard Sprague

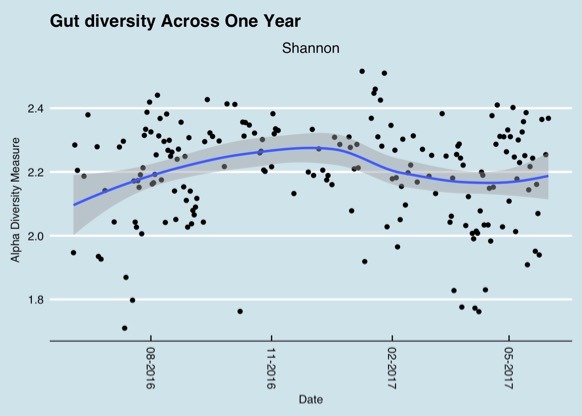

Results from different microbiome testing labs can vary by quite a bit and therefore be confusing. Some of the variety in tests results can be explained when samples are taken at different times. This graph shows gut microbiome diversity over a period of one year.

Changes in the gut microbiome over a one year period (Richard Sprague)

But variations can even be observed during the course of one day as the following chart shows.

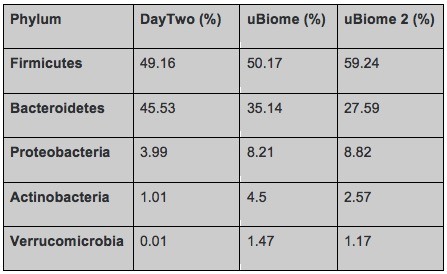

But even having the same sample tested by different labs can lead to different results based on the different methods they use. To interpret data from different labs it is important to focus on the bigger picture, do the lab tests find the same type of bacteria in the same order of abundance. A chart that Richard shared emphasizes that point. The results shown in the table are from the same day, swabbed from the same tube submitted to both companies. The results are different but not extremely different. The top phyla are the same and the abundances are in the same order.

Comparison of gut bacteria phyla and relative abundance in a sample tested by Day Two and uBiome (twice) (Richard Sprague)

Other People, Books & Resources

People

- Elizabeth Bik (@MicrobiomDigest): Richard recommends following Elizabeth on Twitter. She is one of the smartest microbiome scientists he knows, and is very prolific on Twitter. She reads all the publications, and will let you know the ones that matter.

- Rob Knight (@KnightLabNews): Rob Knight is a Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego, among many other things he is a member of the Steering Committee of the Earth Microbiome Project and a co-founder of the American Gut Project. This article in the science magazine Nature gives an overview of his work.

- Eran Segal (@segal_eran): is a computational biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science. He has shown that there is no “One size fits all” diet, and that the very same foods can be good for some and bad for others. He is also one of the founders of the company behind the DayTwo microbiome labs. Eran was interviewed on Quantified Body with another founder of DayTwo, Lihi Segal, here.

- Chris Kresser: A functional medicine practitioner and founder of the California Center of Functional Medicine, a group of doctors that treat patients with a wide range of chronic health problems, from digestive disorders, to chronic infections, to autoimmune disease, to hypothyroidism.

Books

- The Personalized Diet: The Pioneering Program to Lose Weight and Prevent Disease: a diet book by Eran Segal and Eran Elinav that explains why one-size-fits-all diets don’t work and helps readers customize their diet to lose weight and improve health. Robert recommend it specifically because it gives suggestions for how you can test yourself using just a cheap glucose meter.

- Wired to Eat: Damien recommended this book by Robb Wolf which starts with the 30-Day Reset to help people restore normalized blood sugar levels, repair appetite regulation, and reverse insulin resistance. You can also listen to Episode 49 of this podcast for more information. This book also features standard Paleo – based recipes and meal plans for people who suffer from autoimmune diseases, as well as advice on eating a ketogenic diet.

- The Longevity Diet: Discover the New Science Behind Stem Cell Activation and Regeneration to Slow Aging, Fight Disease, and Optimize Weight: book by Valter Longo. Valter is the director of the Longevity Institute at USC in Los Angeles, and of the Program on Longevity and Cancer at IFOM (Molecular Oncology FIRC Institute) in Milan. The book describes the 5 Day Fasting Mimicking Diet which promotes longevity, overall health, and reduce excess fat.

Other

- Richard’s Favorite Books about the microbiome: a list of Richard’s favorite books and the reasons why he rates these books so highly on Medium.

- Richard’s favorite scientific papers about the microbiome: for people who want to deep dive into the science behind the microbiome.

Full Interview Transcript

(0:04:43) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Richard, thanks so much for joining the show. It’s great to have you here.

[Richard Sprague]:My pleasure, I’m a big fan of your podcast. I’m actually a little bit humbled that you’ve asked me to come here and talk today.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well you shouldn’t really be humble because you’re a real data geek when it comes to some of this stuff. So we’ve known each other for a long time because of that.

I can’t remember how we connected? Do you remember how we first connected?

[Richard Sprague]: I’m not sure either. It’s probably some quantified self thing. But I’ve been listening to your podcast since the beginning.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: It wasn’t in person anyway, it was online. I think you must have posted you know what, I think you posted some uBiome analysis, one of the first blog posts, trying to analyze it or something and I found you on Twitter. It might be something like that.

[Richard Sprague]: It could be.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay great, so we’re going to talk about the microbiome because Richard, as I just mentioned in the intro, has been looking into this a lot. And really the first thing is just to get you guys up to speed on all of this, because it’s starting to become quite a complex question.

(0:05:40) We hear a lot about this in podcasts and health podcasts all the time. I think it’s quite a lot more complex than we generally hear. So, Richard, what do you think? What’s going on with all of this? Why is it important, and why are the labs important right now to try and quantify it?

[Richard Sprague]: You’ve had several podcast interviews with people who’ve been working in the microbiome science, but to me the way I would summarize it is that unlike genomics and genetics and your human DNA, which I find very fascinating, but there’s not a whole lot you can do to change it. Despite the fact that there are a lot of genes that are involved, there’s not a whole lot you can do if you find out that you’ve got the gene for this or that. Whereas with the microbiome you’ve got way more genes and you can change them. And I think those two things are part of the reason that I’m very excited about the microbiome.

The other thing is that partly because of that scientists are finding out all kinds of new relationships and associations between the microbiome and just about any human condition you can imagine. Everything from allergies and obesity to Alzheimer’s disease, to mental health issues like depression or schizophrenia.

There’s a relationship with the microbiome there; we don’t understand what they are, but in the last couple of years some really awesome new technology has come online that makes it possible not just to be able to go and see what the microbiome is in an individual person, but now it’s coming to the point where it’s at consumer level pricing. So that you and I can go and figure that out as well and not just wait for some scientist to go and figure it out.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. It’s actually interesting because basically since 2014 there’s been quite a few different labs coming out and these are really some of the firsts.

I mean, genetics was the first with 23andMe and players like that, but it’s one of the first areas where it’s consumer driven testing rather than coming from the medical world, and coming from physicians where they control all that stuff. But really uBiome, which was one of the first commercial players, came out and said this is going to be a consumer driven model at first.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So it’s, I mean I think that’s the other reason there’s a lot of chat about it as well, because it’s more accessible to the general population.

(0:07:45) [Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s right. And in particular I think the 16S, I call it the Hack, made it possible to do something that people weren’t expecting to happen technologically so quickly.

Because if you think about how long and how much money it took to sequence the first human genome back in 2000. You know, that was billions of dollars and involved the cooperation of hundreds, maybe thousands, of scientists around the world.

Well, now we’re talking about at least 10 times, maybe 100 times more genes in a single human being for microbes, and they’re from thousands, maybe tens of thousands of different species. Well, how in the world would you ever sequence all of those genes? It just seems like an impossible problem.

But somebody discovered this trick several years ago that let’s you just look at 200 base pairs on one partial gene, and you can get a rough idea of what’s going on. And that just revolutionized things, because it made it possible now for people to get a hint of what all those microbes are doing.

And that just revolutionized the field. And what’s cool is like you say, since about 2014 it’s been possible for the rest of us to go and access that same kind of technology for basically under 100 dollars.

And that’s just opened up all kinds of new, interesting discoveries.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, yeah. So, we’ll get into why the 16S works, and how it works, in a bit.

(0:09:02) Let’s take a step back because obviously there’s quite a few different technologies out there. When you go to see physicians, when you’re using these technologies, when you’re trying to understand your gut and what’s going on, there’s a fair amount of options. And there’s different options that are being used.

So, Richard could you just give us a quick overview of what kind of technologies are being used currently?

[Richard Sprague]: The first one is culturing. And that’s been around for hundreds, arguably thousands of years, because you essentially, if you know that there’s a microbe involved and if you know which one you want, it’s well understood what kind of things they eat.

So you just take a little bit of a sample, and you put it into a Petri dish and you wait to see what happens. And, scientists know how to culture a lot of the microbes that are important, in particular the pathogens. And that’s kind of the classic way to do it; even today it’s still the gold standard. If you have some kind of medical issue where a doctor wants to confirm for certain that you have such-and-such pathogen, everybody will trust the culturing results.

So that’s kind of the first thing. The problem with culturing is that it only works on certain organisms. And they have to be alive, and it takes a while. It might take several days, or weeks in the case of some microbes.

So the next step was the development of PCR, which is if you know which microbe you’re looking for, you can put into a special machine, polymerase chain reaction, which is well understood technology that’s been around since the early 1990’s.

And they will confirm or deny whether a particular sequence of DNA base pairs are in there or not, which is another way of saying a particular microbe. And that works very quickly; that’s a few hours in some cases. And you can find out for certain whether a particular microbe is there. So the big advantage there is speed.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And also the accuracy, because you can really pinpoint something and if it does show up in the test, you can be sure it’s there.

Whereas even with the cultures, I think one of the issues is contamination. Because you’ve got these Petri dishes growing stuff, who knows sometimes. I’ve done some cultures in the past for different things, and I’ve been very suspect about the actual results that came out in the end. I was like, I think…

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, you have that contamination problem with everything. The bigger issue with culturing and contamination, I think, is that sort of by definition you’re just sitting there waiting for something to happen. And sometimes it happens, sometimes it doesn’t. And, for example, if the pathogen of interest, if it somehow died on the way to the Petri dish, for no good reason, you’re not going to find it

And vice versa if the lab technician somehow exposed something or other to this or that on the way to the Petri dish then you’re going to see something you weren’t expecting.

So the next step up is, we were talking about 16S sequencing. It’s called 16S because there’s a line on the centrifuge when you take a sample and you spin it around enough, there’s a like that’s called the 16S line, which is if you skim off the goop that you find there, you will get one particular gene called the ribosomal rRNA gene. That is part of the genome that’s responsible for building the ribosome, which is an essential part of the way that all cells work.

Well, in bacteria it turns out that all bacteria use a very similar gene. We call it the 16S, the ribosomal gene. And because bacteria are all going to have that same one, in evolutionary terms it’s called conserved, throughout evolution, that it becomes possible to be able to tell the differences in bacteria based on slight variations in that gene.

The gene itself a couple thousand base pairs. But it’s one particular part of that gene called the B4 subunit that’s only, I think it’s 200 base pairs. And so if you just sequence those 200 base pairs, you got a pretty good idea of which microbe it is. Because all the different bacteria that have ever been found on Earth will have that 16S gene, and they will differ just slightly.

And if you’ve got a reference database to be able to see which one is which, and especially if you know that this came from a human gut, right there you’ve suddenly been able to eliminate having to do a gazillions of sequences. Because, sequencing something for only 200 base pairs is pretty cheap, you’re able to get the whole cost down to less than 100 dollars.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So they called this hyper-variable because, I mean the interesting thing about this is that that region just varies greatly. So that’s why you’re able to identify these different genus of these sometimes species, if it happens to be a species that has more variation on that. But that’s really the key to it; it just varies so much that you’re able to identify the different things in it.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, and it’s pretty cool. It’s a really amazing shortcut, when you think about it.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right

[Richard Sprague]: That you’re able to go from literally millions of genes, down to exactly which biome species it is. That’s pretty cool.

(0:13:44) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: And so those were the first tests that came out with the uBiome, the American Gut and some others. There’s Atlas BioMed now in Russia and the UK as well, but I’d say most of the labs are using it, the 16S. Is that the one you’ve seen because you’ve seen some others in their states, and new ones that I hadn’t come across.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right. I mean there are lots. It’s not that hard for a lab to do 16S sequencing. In fact probably most universities do this routinely. So anybody who’s got an Illumina gene sequencer can do 16S sequencing. It’s not, the basic ideas are pretty well understood.

Also the pipeline, the software pipeline where you go from the output of the gene sequencer to actually telling you which part of the taxonomy it is. All of that stuff is available on Open Source software. Just about anyone, any feasible lab can go do it.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: For me, when I was first getting my uBiome stuff I was trying to understand it better and I just accessed the Open Source stuff. And actually, you think it’s going to be super complicated. I didn’t do a degree in bioinformatics or anything, but actually it wasn’t that complicated.

I managed to look into, and you’ve been doing a lot of that and posting your results up online as well. That’s how you got into it. So it’s actually very accessible, which is great as well.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right. And it’s pretty easy if you have questions to find bioinformatics experts around who will answer your questions. Because like I said, this whole technology and the basics behind it pretty well understood.

(0:15:04) So, that’s 16S. The next step up requires a lot more detail and a lot more sequencing. People call it metagenomic sequencing. And essentially what you’re doing is you’re taking the entire sample, you blow it up people say you shoot a shotgun at it and you get all these little parts flying out.

And then a computer takes, it’s almost like a big jigsaw puzzle and reassembles it. And the advantage of metagenomic sequencing is that now you’re not just looking at that one 16S rRNA gene, you’re looking at all the genes. And so it’s a lot more comprehensive.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And then you can get species, strain level identification.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Because the one thing I struggled with when I was doing a few little projects on this was sometimes if you’re unlucky and you’re trying to identify some certain species or definitely strains or even genus in some cases the 16S can’t work. It’s very difficult to get that type of level of granularity of information out of it sometimes.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s right. And unfortunately that matters. So one of the reasons why something turns into a pathogen, it turns into a pathogen and your body isn’t able to fight it off because it may be only off one or two base pairs.

So there are versions of E-coli that are only a couple of base pairs different than the ones that are highly pathogenic. And that’s because the bacteria are able to mutate much faster than a human can. Obviously it takes us a whole lifetime before you pass on a genetic mutation.

Whereas the bacteria do this all the time. So, unfortunately most of the pathogens that you’ll see out there are just a couple of base pairs different, and you can’t tell them apart with 16S.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So when you say a couple of base pairs, that’s the strain level? Is that the level of strain difference?

[Richard Sprague]: That could be the strain level or the species level, it depends where on the gene the mutation happened.

(0:16:50) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So strain for the guys at home is the absolutely tiniest, basically if you think of a human mutation, that’s kind of a strain. Do you say that’s correct Richard?

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, the way I would describe it is that you take a dog or a wolf, both are part of the genus canine. Okay? It would matter a lot to to whether it’s a dog or a wolf at your door, it matters a lot.

So just knowing the genus didn’t help you a whole lot. The species will tell you now that it’s a dog versus a wolf. The strain would tell you that it’s a poodle or a bulldog.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, that’s a good example.

[Richard Sprague]: Now, there are lots of cases where it might make a big difference whether it’s a Rottweiler or…

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: A poodle, yeah.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah. So you’ll need this kind of metagenomic sequencing to be able to tell that level of difference. And unfortunately a lot of times it matters.

(0:17:40) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So I had on a PCR test, just in November, fibrocholera. In other words, cholera turned up in my test. And I was looking at it like, this can’t be.

You start looking into it and you’re like, wow. I had diarrhea, stool problems, for about a week, which was very unusual, liquid diarrhea. And so I looked into this and thought, I can’t have had cholera.

And when you look into it, there’s only two specific strains of that with small modifications which cause the epidemics. The other ones, they’re dangerous, they’re not nice, they give you diarrhea for a week and it’s not nice. But it’s actually some very rare strains that come out, those are the only ones that cause the really lethal epidemics that we’ve seen in the past.

[Richard Sprague]: Could be. And in fact, and this is where it gets really complicated, it could be that the particular strain that you have will out-compete the bad guy. So having it will actually help prevent you from getting cholera.

That’s the sort of thing that happens. That’s why it’s really hard to look at the presence or absence of a particular microbe and say in isolation whether this is good or bad.

Usually it will turn out that something that’s pathogenic will have one other characteristic, which is that it is super hyper-competitive, and it will just eat up everything else and take over. And you’ll know within days, maybe hours, whether it’s bad or not.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Richard Sprague]: So a lot of times if you just see a little bit of this or that in there, that’s just life.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. But I think this is really, really important because I think a lot of the people who are finding species and I think we’ve both been guilty of it too, Richard. We find a species in one of our microbiome tests, so we dig into it and we research it. Especially with the 16S lab, where it’s maybe at a higher level that it’s been identified, I think it can lead to a lot of work with no outcome there, because you’re not as sure what you’re actually dealing with.

And the best thing there is probably to escalate it, basically. If you found something in a 16S you could escalate it to a shotgun, or better PCR for the specific one that may be a concern.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s right. And the other kind of thing to always keep in mind with all those sort of testing is that we do have a lot of data. And that’s dangerous because now suddenly you’re being flooded with a whole bunch of data, and it’s easy to overreact. Because you’ll find all kinds of things, and it takes a long time to be able to sit back and look at it a little bit more objectively and say you know what, this is just the nature of the technology. We’re at the cutting edge; we’re going to find some stuff, don’t get too excited.

(0:20:10) So, going back to the list of different ways you can measure the microbiome. One of the other areas that’s been very exciting, this is kind of where the real cutting edge is now. It’s called transcriptomics, and that’s based on the observation that just because a gene or a microbe is there, it doesn’t mean anything in and of itself.

What you really care about is whether that gene is producing the proteins that are the building blocks of life. And the way that you tell that is by the RNA that it’s producing while it’s doing all of it’s copying and transcribing these genes. So people call it transcriptomics because you’re transcribing this gene into RNA.

And there are some new tests that are coming on that let you be able to look at that. Now, that has been extremely expensive. Like I said, it’s the cutting edge and you’re talking about RNA, which is a very difficult to handle molecule; it takes special kinds of labs to be able to do that.

And what’s very exiting is that now that is becoming possible to do at consumer level pricing as well. But that’s definitly, I think most of us would agree that that’s where the future is going to be.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and then after that you have proteinomics, actually looking at the proteins. Because basically what we’re talking about is the chain of events in order to create the different molecules in your body.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And it goes all the way down the line from genetics, transcriptomics, proteinomics, to metabolomics.

[Richard Sprague]: Metabolomics, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And it’s all great stuff.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: The beauty of it is one day we’ll probably have all them and actually understand what’s going on in the body.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s right, yeah. I should also mention there are lots and lots of different tricks along the way to try to mimic what you get out of metabolomics or transcriptomics without having to do a full blood panel and that sort of stuff. One of them is called functional genomics.

For example, uBiome you can get this thing called a KEGG analysis. And that’s fairly common. That’s kind of a way to guess what sort of metabolites might be produced by this particular gene.

I don’t think it’s of super huge value. A lot of people will point to that as being evidence that such-and-such type of metabolite is present in my body. And you’ll hear that every now and then, it’s called KEGG analysis, another way to talk about it. But what I’m excited about is that now I think we’re able to move beyond that to looking more directly at what the specific thing going on in your body is.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]:With the transcriptome?

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]:Yeah, I mean you can see that on uBiome, right. If anyone has a uBiome test at home they have the functional part that is displayed. Do they still have those charts, I haven’t checked for a while.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So that would be your KEGG analysis you’re talking about, correct?

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And it’s things like, they’ll say you have caffeine metabolism and other things going on.

[Richard Sprague]: Or yeah, Vitamin D or this or that, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, yeah. I thought it was interesting because you told the story of where that came from and why we should be maybe a little conservative in thinking that that’s accurate.

[Richard Sprague]: Well it’s based on some experimental studies that were done a long time ago in Kyoto actually that’s why it’s called KEGG. It’s Kyoto something or other, EGG.

They essentially took a lot of genetic samples and they looked to see what kind of metabolites were produced. Well based on those experiments and they were carefully done experiments people are estimating when you’ve got a particular set of genes in your sample what kind of metabolites they might produce as well.

And that’s arguably better than knowing nothing at all, but I wouldn’t rely on it to be able to tell exactly how much caffeine I’m metabolizing or Vitamin D, etc.

You find a lot of this kind of stuff with genomics where somebody’s got some kind of tool, and it’s experimental. They’re just trying it out, and we’ll see how it works. And this is one of those cases. So I wouldn’t put a whole lot of stock in it.

(0:17:40) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. Right. Great. I think another important question is why use genomics lab to understand the microbiome versus the other ones? The cultures, for example. They’re all genomics, right? The PCR, the…

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah. The biggest advantages of the genomic approaches are that it works on all of the microbes that are in the sample.

Remember with culturing, unfortunately, unless you reproduce the exact environment of your gut, which means anaerobic, no oxygen there, it’s got all the different microbes in combination and some of them are producing things that the other ones eat and need. There’s this whole community, so unless you’ve got that whole thing you can’t necessarily culture what you’re looking for.

Whereas the genomics which just says, you know what, we’re just going to look at every single gene in the whole thing. As a result, people have found that it’s well over 90 percent of all the microbes in your body can’t be cultured. We find brand new ones all the time.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. So that’s what’s going on, and that’s only been enabled by the genomics approach.

Because as you’re explaining, it’s super complicated; all the interactions between the bacteria and they rely on each other to survive.

As soon as you remove them and you’re trying to culture them or something, you remove that whole environment that they’ve been able to survive and breed in. And they need the metabolites, the things coming from the other bacteria and they’re just not there, potentially, because you kill them off.

The way that culturing works is basically you’re trying to separate out the things you’re trying to grow so that they show up in color and stuff. But by separating out and killing off the other stuff and not letting it grow, you’re basically killing off the ones that you want to grow anyway, in some cases, because they need the other bacteria.

[Richard Sprague]: Yup, that’s right. And it turns out that in a lot of interesting cases like some of the pathogens, maybe that’s good enough. But if you’re really trying to understand the whole richness of the microbiome, you’ll have to go to the genomics approaches.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Excellent.

[Richard Sprague]: So, now I will say, and I think we should put a big caveat in here. The genomics approach is nice to be able to get a look at all the genes that are there.

When I first started studying this, I thought, wow this is awesome, I’ll finally know what’s going on in my body. But I discovered that it’s actually much, much more complicated than it looks. As you can imagine, if you’ve got millions of organisms in a sample and you want to turn that into some useful data summary, there are a lot of steps that the lab has to go through.

And the steps are everything from the way that you happen to insert the sample into the vial, and it goes through the mail, and then how the lab tech handles it. All the way up to the bioinformatics pipeline where they’re going to process all of these numbers that come out of the sequencer and turn that into whatever taxonomy.

There are dozens of steps involved, and in any of those steps if the lab does it slightly differently than the other lab, you’re going to get different results.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Correct me if I’m wrong, because Richard has been at uBiome for quite a while so he’s had a closer experience with all of this. It seems like the bioinformatics pipeline, which is basically a series of calculations you’re going to make based on a database you have of references.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And that comes from research of things saying that this piece of code means that this species, genus, exists, and so on. So you’re using a database of references in order, and you’re pushing it through this pipeline of algorithms, basically, that looks at the database checks and categorizes things. So that’s what that bioinformatics pipeline is actually doing.

And it turns out that everyone’s creating their own bioinformatics pipeline, and they’re using different databases, different reference databases

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right.

(0:27:30) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: And then we get quite different results, which is the next question I wanted to bring up. Why are we getting different results from different labs?

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah. And this is a little scary for me when I started digging into this, because I had spent a lot of time getting to know the different papers and the different labs and the different conclusions that people had come up with.

And you can put it in the show notes, but there’s a chart that I like to see that was from a publication in Science a couple of years ago where somebody actually went through and compared all the different big microbiome categorization projects and looked at just some of the common genus level microbes that they found in there. (publication referenced by Richard)

And it’s a little scary, because you look at it and you see that oh, the Human Microbiome Project says that such-and-such genus is dominant, and this one big study of like 4,000 individuals in the Netherlands found that no, that’s not the one that’s dominant, it’s a different one. And we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of individuals, so you’d think that they would all kind of average out, but that’s not the case.

And even American Gut and uBiome, if you look at their overall pictures, when they look at firmicutes versus bacteroidetes, or some of the other common ones, the results are just different. And you could say that, well maybe that’s because the type of people who send samples to uBiome are different than the ones who don’t.

But you’re talking about enough people that that’s a little bit harder to swallow. So what’s really going on is that a lab makes just one little change in, for example, how many times they PCR something before they submitted the sequencer, just one little change like that will express different levels of DNA, and then poof, you’ve got a different result.

And each of the labs if they use different reference databases, like you were saying, those references could be slightly different. If they find that a particular gene, they look it up in one reference database and it says that, oh this is bifidobacterium such-and-such. Well another lab might have called it something else.

So you just have to be a little careful. The good news is, and this is the way I look at this, if you’re going through the same lab most labs, I give them the benefit of doubt that they’re usually pretty careful. And the scientists behind this are usually pretty cautious about how they do protocols.

So you could usually trust when you submit a sample to one lab that it’s comparable to the sample the next time you submit it to the same lab. It’s just you have to be a little bit careful if you see a paper that says that they found that such-and-such microbe is associated with such-and-such condition, don’t just automatically assume that, oh my uBiome results says I have that microbe then that must mean I have such-and-such association.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, you could look at which lab did they use. Basically. And it’s a shame that there isn’t a standardized reference database, but it’s also the nature of the technology and the way it’s developing really.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s right, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Because it’s been opened up, and we have this commercial model. Which is actually enabling really the explosion of data gathering.

I don’t know how many samples, but basically there weren’t enough samples out there being collected and so on to advance science, right? So you have these commercial companies, like uBiome and so on, and they’ve made it feasible to get a large number of samples. I don’t know if you know how many samples uBiome has now, or if that’s disclosable.

[Richard Sprague]: I think the last announcement they’ve made is it’s well over a quarter million. I don’t know the exact number what they’ve announced, but it’s a lot of samples.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. And then you learn a lot from that massive data, you start the see the correlations. All the labs have, I think, questionnaires filled in as well so that they can start to see if there are some things that are related to Paleo diets, Keto diets, to antibiotics abuse. Not that many people like to abuse antibiotics in particular, but it has been done.

So I think it’s really interesting that all this data is being collected. And the nice thing, also, is that they keep the sequences, correct? This is definitely an area you’ll know more about than me, but if we wanted to run this through a different bioinformatics pipeline later, could we do that?

[Richard Sprague]: It would be tricky. Are you saying like if I submitted the same sample to uBiome and later on to someone else?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: No I’m saying uBiome has a million samples, for example. And they have a particular bioinformatics pipeline today which says that, for example, I have a species we’ll talk about the cholera species that came up in my PCR test recently. But maybe in the five years time they’ll improve their reference database.

[Richard Sprague]:Yeah, that’s right. So, in fact, they could just go back to the shelf and look up and see your old sample and then run it through something else, and they might find something new. That’s right, yeah.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right, so if they ever do decide that it’s important to change their bioinformatics pipeline, they could…just run it again.

[Richard Sprague]: Yup, you could run it again. And in fact, if you have the fast Q file, the raw output from the sequencer, it’s possible to run it through a different pipeline there as well. And if in the future somebody comes up with a better reference database, for example, it’s possible to take that same exact fast Q file and come up with a different answer.

(0:32:28) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Well exactly. So they have all these fast Q files on a server somewhere, I’m guessing. Right? So these are the things you could run through a bioinformatics pipeline and get different answers. So that data is going to be invaluable, incredibly valuable.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, you’ll be able to find new insights from the old data in the future.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Right. Richard and I were just talking before we started this episode, some of this stuff may be challenging to get without visuals.

Whenever we’re mentioning something and it sounds complicated, we’ll probably throw a chart in there because we’ll realize that, and we’ll be like yeah, that one deserves a visual chart. So we might go over the concept relatively quickly, because we realize we’re not going to get there on audio but try and provide some visual aides in the show notes.

(0:33:13) Let’s talk about the actual labs now. What are all these labs? We’ve just kind of bounced around a few of them already, but what’s the landscape look like? It looks like it’s kind of exploding in the last few years, right? So I think uBiome and American Gut were around in 2014, and since then there’s quite a few different labs that have come out.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s right. I’m actually curious also about you, because you’ve done more of the culturing than I have. And what kind of labs you’ve had experience with on the culturing side.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so there’s basically a lot of functional medicine practitioners and hospitals in general will use the culture approach.

So I’ve done many, many different cultures over time and eventually this led me to running two different cultures; this was quite a few years after having started the Doctors Data and the BioHealth lab side-by-side, because they have different strengths and weaknesses. They’re both culture based test, and pretty consistently some things would turn up, but not necessarily on both of them.

I was working with Chris Kresser’s California Center of Functional Medicine there. And I like those guys because they’re very conservative about tests; you may have come across them as well Richard, I know they were talking to uBiome.

And they’re very conservative about their tests. They look for the studies, they look and they have a very large population of clients as well. And they’ve been running for many years. So I like the fact that they’ve been doing that for a while, and they have changed their tests over time.

And they, I think they may have moved on a little bit from these tests, but a couple of years ago when I was doing a lot of this with them they were running both of those side-by-side. That’s a little bit expensive, but it did tend to give us pretty clear…

[Richard Sprague]: So, did you submit the same exact sample to two different labs?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. Each time. Yeah, that was their protocol. Basically they…

[Richard Sprague]: And can I ask you, those culturing labs were they, did you have to poop in a box or did you just send a swab?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: We used these kind of tiny vials for the uBiome, right? Where you put this really little vial, I mean basically the size of the end of your thumb. The culture labs, they’re larger; kind of three times a test tube size. They’re like a big test tube.

[Richard Sprague]: So a couple of tablespoons?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. And normally, actually, you have four of those for each kit. So there’s a lot of spooning and scooping that goes on for a little while into these different containers because they’ve got different assays they’re running there and they’re trying to preserve and do different things in each of those vials so they can look for different things, parasites and so on.

So it was quite a time consuming process when you’re doing that.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah. And did you have to go to the hospital or the doctors office to do it?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, you do these from home. They send you the kits, and you sit on the floor scooping. I would lock myself in there for half an hour and scoop away.

[Richard Sprague]: And did the tests agree with each other? You said you submitted from the same sample.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Sometimes, sometimes they didn’t.

The reason they were using those in particular was because they felt they had different strengths as well. The last I heard some people feel BioHealth was a little more useful and picked up more stuff.

And again it comes back to our discussion of sensitivity, whether it’s picking up stuff. And that is the concern with a lot of physicians that it’s not picking up stuff, and it doesn’t do it reliably.

So I actually experienced this because I did many of these, over time. We were doing them every couple of months or so to see if the treatments we were doing against parasites like blastocystis hominis I had that for a while, and it’s quite a common thing but it can be a bit of an annoyance in the gut.

And we would do a protocol to get rid of it; we would retest it, it’d be gone. And we’d wait. You have to wait after your treatment, obviously, in order to let things settle down and then see if they grow back. And it would be gone for maybe two tests, and then it would come back again; it would just pop up on one of the tests.

So there’s a bit of inconsistency, and it’s a little bit worrying. For that reason you end up doing a lot of these, and they can be expensive.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, interesting.

I don’t know too much about Doctors Data or Biohealth.

I talked to functional medicine practitioner who used GI Effects. And that seems to be, at least in the Seattle area where I am and a lot of naturopaths, that seems to be kind of the one that most people use. The functional medicine people that I talk to are pretty positive about it, and they say that it actually produces very actionable results for treatment.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Richard Sprague]: It seems the one to beat.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: That was actually the first one I ever did, I think back in 2011 or something. It was MetaMetics previously and Genoma acquired that company. And MetaMetrics was very well respected as a company, so it was a good acquisition.

It came up with some stuff. And that is a combination of the culturing approach and PCR which we were talking about later, which is a genome sequencing but quite accurate. If you see something with PCR, it’s there. That’s a high probability.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, and I would say I’m not a doctor and please don’t trust my advice but if I did have some kind of gut issue I would want the functional doctor to use what he or she is familiar with and comfortable with, and they seem to be comfortable with this. And I would trust those results because they’ve been used for years and years and doctors have learned what work or don’t work about them.

I look at the other genomic results like the 16S and metagenomic results as being kind of cool for someone like me, and definitely worth watching for future potential. But if I were really sick, I would want to stick with what the doctors trust.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, exactly. And so I know some functional medicine practices have evaluated 16S based testing, and have done trials with it. But so far they’re like, this isn’t going to be good enough in terms of diagnostics, and also just the cost. Maybe it would pull out some things sometimes and be a little bit indicative of something, or just help you to explore doing a PCR with something. But they felt like the cost benefit and just the kind of time involved in getting a patient to do it wasn’t worth it at this point.

(0:39:10) [Richard Sprague]: Yeah, maybe. Now, on the other hand, there are a lot of conditions where the traditional culturing, or even the PCR approaches, can’t find out what’s wrong, and they don’t know what’s going on.

And that, I think, that’s where the place is for a little bit more experimental and you want to look at a bigger picture. And that’s where you get the 16S and metagenomic approaches because you will see a lot more.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely.

[Richard Sprague]: And after you’ve looked at zillions of samples the way that I have, you do start to see patterns. And you start to see when something looks anomalous, and you say, hmm. And those are the kind of things that if you’re just relying on culturing approaches you probably wouldn’t be able to see

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely.

I’ve been really interested in the shotgun approach in particular for this, to pick up things that, as we said before, with PCR basically you have to say I want to find a poodle. You know? Or I want to find a dog in the mass of everything in the world. So you have to really know what you’re looking for, otherwise you’ll just get a negative and it costs money.

Whereas the shotgun, if you don’t know what you’re looking for but you think there’s something there it’s a good idea to do a shotgun to give you an indication. So I did a recent one, Richard and I were talking about the shotgun approach which is looking for pathogens and things like this, which is the Aperiomics, the lab test.

And I did a shotgun sample of my poop and, you know, there were a few different pathogens and some others that came up which were unknowns. A lot of them were unknowns, actually, because it’s a relatively new service; and this is where you see the bioinformatics pipeline, their reference database and so on.

They told me the benchmarks they have so far. They don’t have enough data, so there’s some interesting stuff, but there’s a lot of unknowns; we don’t know if its pathogenic or not because a lot of people have this and they’re going fine.

But I think that for me was an interesting test because it was using shotgun just to potentially pick up something interesting, and then go after it with PCR.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s interesting. And I would love to see results that people do side-by-side if you submit the same sample to two different labs. It would be really interesting to compare that.

(0:41:12) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, so I did that with the GI Map from Diagnostic Laboratories. Also uBiome, but unfortunately somehow that was lost, either in the post or I don’t know what happened with it. And I did Free Labs.

GI Map, we haven’t discussed, is a PCR based test. And that’s from Diagnostic Laboratories. And there’s a lot of functional medicine practitioners who are now looking at that one. Because it is PCR based, so again if you pick something up and it’s looking for quite a number of problematic bacteria, parasites, and so on, then it can be pretty useful. It’s a little bit more expensive, but that’s a good one.

So I ran that next to the Aperiomics, and I had that back. And I was trying to cross them, but nothing crossed actually.

[Richard Sprague]: Oh you didn’t find any, there was no consistency between the two?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: No, I didn’t find the same. So I found the cholera in the GI Map. So I trust that because it’s PCR based. It didn’t turn up in the shotgun, which could be the reference database that they haven’t put that species in, or that specific strain in even. Or it could be the bioinformatics pipeline that they haven’t built out yet.

There’s so many different reasons that that might not be. But it goes back to what Richard was saying earlier, is that if you’re using different labs it’s not necessarily going to pick up the same stuff at this stage.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s interesting if they couldn’t find cholera in two different samples.

Part of it also could be if we’re talking about minute amounts, even the metagenomic approaches you’re only looking at a certain number of, you’re not looking at every single gene in there. You’re still looking at a subset of all the different genes, because you can’t sequence all gazillion of them.

The PCR approach though, you’re looking for a particular one. So you stick in some primers that will cut every single copy of DNA that has that one in there. You’d have to ask somebody who’s more knowledgeable about lab science than I am to state this more unequivocally, but when you do that you will know that the following DNA snippets came from that microbe.

Whereas with the shotgun approach, you’re going to know at a broad level, because you’ve looked at as many as you could, but you haven’t looked at every single one of them

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah.

[Richard Sprague]: And when you’re talking about minute amounts, that might make the difference.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, I think the nice thing about, going back to genomics, is that it will get better over time, as these databases, these bioinformatics pipelines, as each company basically gathers data and experience. And eventually, hopefully, there will be some type of collaboration. I don’t know what would be up in the future, but it would be nice if there was a way to match these together and get…

[Richard Sprague]: That would be neat, yeah. That would be neat to have a bunch of people all comparing our results from the different labs.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, and trying to build conversion tables or something. Something like a pool where you can convert your uBiome into your American Gut, or whatever you wanted. And it would be more comparable.

(0:44:07) [Richard Sprague]: And see how you compare, yeah. In fact, actually it’s funny because American Gut is one of the few labs that you submit the sample dry. In other words, you just put it on a Q-tip and you send it in dry. You don’t put it in a special upright vial.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Nothing? Okay, interesting.

[Richard Sprague]: And I asked the lab about that, because that’s kind of odd. And they know that there are certain species that when they are dry they continue to multiply. Because it’s not dead when it comes out of your body. And some of them when they’re exposed to oxygen immediately die, but some of them don’t. In fact, some of the thrive, and you get a bloom actually in some species.

And what American Gut does and they’ve written a paper about this, they’re very upfront about it they run, in their bioinformatics pipeline, they’ve already tested which species are thriving in an oxygen environment, and they filter those out. And they say oh well you collected a sample on such-and-such date, that means that this much time has passed which means that likely this much of this species has bloomed. And we’re just going to go and adjust the final result that way.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Whereas basically uBiome’s test and others, they’re killing all the bacteria straight away to preserve them in the state they were in the stool.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah. And again, that’s going to be a difference in the pipeline. You’re going to get different results.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: I mean, I can imagine. I mean that introduces basically another variable. I wonder why they didn’t decide to eliminate that.

[Richard Sprague]: Well the reason they didn’t do that is because the people at American Gut are super careful scientists, and what they care mostly about is consistency across all their different samples. They want to make sure that every single sample is conducted under the same conditions.

And they also at least in the beginning were working a lot in environments like outside the United States where maybe the collection procedure was maybe a little bit more erratic. And they just wanted it so that they could take all the different samples and treat them exactly the same way.

They’ve got a paper on this where they show, you know, that it doesn’t matter as much as you might think, but still. Yeah, it’s another area where the pipeline is going to be different.

(0:45:55) For you guys at home, just a quick reference there. I spoke to Rob Knight from the American Gut a while back, so if you wanted to know more about what he was doing there. He talks about where they got the first data and so on for that project.

(0:46:10) Okay, great. How about the 16S labs? Because you know all the 16S labs really well.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, well let’s talk about the 16S.

Now, first of all, I want to repeat in full transparency, I am a friend of uBiome. I’m a former employee. I’ve been a happy user of them for a long time. But I have spent time with their scientists; I trust their scientists. I think they’re pretty careful about how they put stuff in the lab.

Now that said, there are lots of other labs that I’ve worked with as well, and I’ll just go through the differences.

We talked about American Gut. I think that American Gut is scientifically they’re the most sound lab. You’ve had Rob Knight on this show, you know he’s a very smart guy, well published, extremely careful scientist, and knows everybody.

They have published a lot of results based on their American Gut cohorts, and they’ll continue publishing. They take their science very seriously. The other thing about them is they’re ultra transparent.

Every single one of their software tools that they use are all Open Source. They anonymize, and then anybody who wants to can go look at their data and reproduce their results. In fact, they even have Python notebooks where if you don’t trust something that they publish in a paper you can go run it yourself down your own Python and see.

So it’s very transparent from that point of view.

The other company that I would call out is a newer company called Thryve in Santa Clara. They’re focusing on personalized probiotics, but the CEO Richard Lin is an example of the kind of person I like to see running one of these companies because he cares a lot.

He’s been trying to solve some of his own issues, and so he founded a company, essentially, to go and help resolve that. So he cares a lot and he’s especially focused on actionable results. So I like them.

There are lots of other labs; I won’t go into all the names, I haven’t tried a lot of them.

One that I will bring up though is a company called Gencove that focuses mostly on genomics. So they’ll take a mouth sample. But what’s cool about them is that they’ll run their mouth sample, the swab that you give from your mouth, you get the DNA results just like with 23andMe; it’s very comparable to 23andMe. But they also give you the microbiome breakdown.

So there’s that company. And there are lots of other companies that are doing 16S in one form or another.

(0:48:20) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: So that’s very similar to the Atlas Biomed guys, who actually came from Russia. So they were doing studies in Russia, and now they’re in the UK as well, so they got the two populations. So they’ve combined in their interface the DNA and the microbiome.

So it’s quite interesting. I would say they’ve got a lot of recommendations. We’ll get into this in a little bit but they got a lot of recommendations in there, and study references and stuff like that. It’s quite interesting; they’re quite strong on the recommendations from the data.

[Richard Sprague]: Interesting. Do they, what kind of sample do you give them? Is it a mouth swab, or both, or blood? What do you give them?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Sorry, this is for the gut, right?

[Richard Sprague]: So it’s just gut, okay.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Oh, for the DNA it’s saliva, you’re correct.

[Richard Sprague]: Yes.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And then for the gut it’s the usual poop thing.

[Richard Sprague]: Yes, okay.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: So you do the test and the same time. Or you can send the DNA whenever you wanted.

[Richard Sprague]: So they’re two separate samples?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, that’s right.

They’re trying to combine to get more information, to see correlations, things like that.

[Richard Sprague]: That’s real interesting.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And their plan is, I think this will get more interesting. I went to see them last week and so I was talking to them a lot.

And basically their plan is now to get into blood tests as well. And to bring this kind of information to clinicians, where you combine DNA microbiome and blood tests results, metabolomics. And some of the standard stuff as well, like information whatever it is that doctors have been using for a long time. And you can give a bit more context.

So they haven’t figured how they’re going to do that, but the idea is to provide more context around these blood tests to try and make the links and stuff like that to provide a better tool, basically, for looking at patients.

And I think if it’s done that way, led by blood tests which have been used for a very long time in diagnostics anyway, and you add information and context with the DNA and the microbiome, then that actually sound quite useful.

(0:50:11) [Richard Sprague]:That’s right. There’s another company in the US called Arivale, based here in Seattle, and they are now available in the West Coast, California and here. They might be nationwide at this point. But it’s a very similar kind of thing.

I think it’s 1000 dollars, for a one year program. They do a 30x genomic sequence. They test your microbiome, they do your blood test, and there are a couple of other things. They give you a FitBit and measure activity.

And then they assign you a personal nutritionist and you have once a month meetings with them, and you can ask them email questions, and that sort of stuff. And they work with you on whatever issue you want.

And I think that is the direction that I think if you’re seriously trying to solve a problem, that’s what you should be doing. Because it’s this holistic look at the blood results, the microbiome, the genetics and all that stuff together.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: And consultation. And experts who actually help you work through it.

Because right now, frankly, a lot of these services had to start a consumer facing in order to get the volume of data and build up their databases, right? Because that was the only way that you were going to get enough data to be able to start seeing patterns and start getting past this first hurdle.

And I think it was always sold like that anyway; this is informational, it’s not diagnostic, it’s not supposed to be used like that. That’s really the idea.

[Richard Sprague]: Yup.

(0:51:26) [Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay. So that’s 16S, and like I said Atlas Biomed that was a 16S as well. And then we have the metagenomic shotgun ones, which I was quite excited about.

I spoke to Eran Segal and Lihi Segal in a previous episode about their work, and that resulted in Day Two. So I was kind of looking forward to that, because it was the first shotgun service to come out that was a reasonable cost. I think at that time it was like 200 or 300 dollars.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah, that’s right.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah. So there’s that one. And you’ve done that as well, and you published a review about it. So what did you think of Day Two?

[Richard Sprague]: I thought Day Two is very cool. You submit the sample, it took a while to get back, but they’re just getting started.

What’s neat about it is Eran Segal, as you mentioned, did a lot of really cool research where they were able to identify, I guess, glucose response levels and it’s dependence on what’s going on in the microbiome. And so by looking just at the microbiome they’re able to tell, oh your insulin levels are likely to respond to what’s in your diet.

And they ran this big machine learning algorithm against all the different kinds of food types. And they had, I think 1000 volunteers and they did a whole bunch of studies.

And now Day Two gives you an app that goes through the food groups and tells you how likely you are to respond, well or poorly, to a particular type of food. It’s very well done.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: In terms of glucose response, right? It’s just glucose response. So we know that.

It’s been pretty cool. And they had large studies; they had a pretty large population, over 1000 people.

[Richard Sprague]: Yeah. It was, and they’re careful scientists and they published their results.

And kind of the interesting take-away from Eran Segal’s work was that there are some people who, your standard diet advice says you should always eat the whole grain version instead of the white bread version. But there are some people who it’s the exact opposite advice. And this algorithm seems to be pretty good at telling which one you are.

So in my case, for example, with Day Two it’s showing that I should be eating things with more fat in them.

So yeah, there you go Mr. Ketogenic guy. And it was pretty accurate for me. It showed, for example, I’m not lactose intolerant; I can handle dairy and it recommends that I have dairy. And I found most of the suggestions to be reasonable.

The other nice thing about them is they’re not based just on a particular food, but they recognize that food is in context. So having a slice of toast is not the same as having a slice of toast with some butter on it; the way that your body is going to respond is totally different. And they have a lot of recommendations for that.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Absolutely.

[Richard Sprague]: So I’m pretty impressed. I’m waiting to see how they do. A lot of the initial research was all done in Israel. So they’re running a study now I guess in the United States. And I think actually when you had them on your podcast I think one thing they mentioned, they’re doing something with Mayo Clinic, I think.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

[Richard Sprague]: So I’m looking forward to seeing how that turns out in the next couple of years.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Yeah, that would be pretty cool when they get more data. Because I think, personally, glucose response is one of the highest impact things you can do relatively simply by changing your diet. Sometimes sleep and other factors as well, but it’s really important.

So going back to this personalized…

[Richard Sprague]: Just one quick thing, did you see the new book that Eran Segal and his co-author put out?

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: No, I didn’t.

[Richard Sprague]: It’s called The Personalized Diet. That’s worth reading. Yeah, that’s worth reading. It’s called The Personalized Diet.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Okay, great.

[Richard Sprague]: Go check it. It just came out, and I just read it it’s a wonderful book.

[Damien Blenkinsopp]: Oh, awesome.

[Richard Sprague]: It goes into a lot of… And what’s cool is in the end, he gives suggestions for how you can test yourself using just a cheap glucose meter, and gives suggestions as part of it. It’s kind of cool.